Is droichead í Brigid – Brigid is a bridge.

A pre-Christian Celtic goddess and a Christian Patroness Saint – Brigid’s twin-soul bridges the deep-rooted ancient and medieval traditions of Ireland during this transformative time of year as we weave our rushes and reeds together to create St. Brigid crosses – celebrating spring.

For when we behold the woven cross that harmoniously unites our heartland within our hands, we hold the spirit of Celtic-Christian worlds.

My mother, Jacqueline Keenaghan, weaving a St. Brigid’s Cross.

Old Irish maps also offer further insight into our understanding of Celtic-Christanity. If we know how to keenly read the geographical and topographical features on maps, like realising how to skillfully weave the reed and rush into a cross, we can perceive aligned patterns that may be created by design in the Irish landscape.

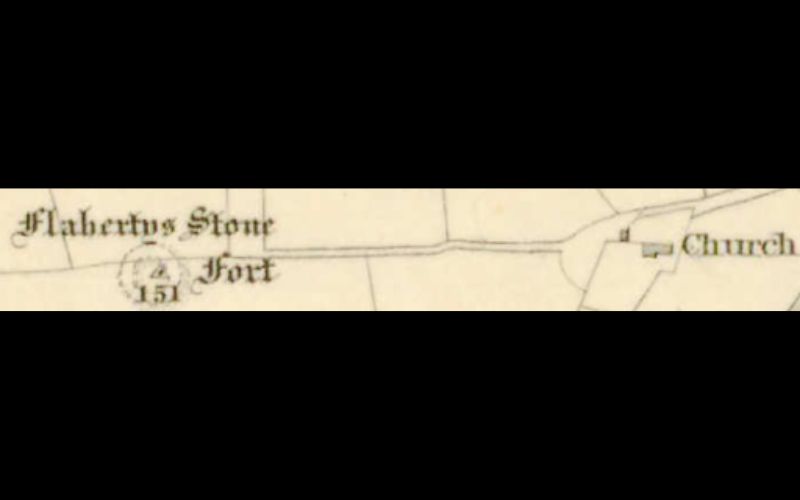

A good touchstone for imagining one of these Celtic-Christian worlds centers on the pre-Christian and Christian historical sites of Flaherty’s Stone and Finner Church in Bundoran, Co Donegal.

Finner’s ancient monumental landscape abounds with megalithic structures. Giants’ graves, middens, ring-forts and standing stones surround this liminal space where sand meets land.

Unfortunately, only a small part of Finner’s otherworldly historic landscape has been studied, but as the shifting sands and rising swells are felt by the strollers and surfers on Tullan Strand – the tide is now hopefully beginning to turn.

Thanks to Magh Éne Historical Society and the support from people in the community, the first preliminary step has been taken towards revealing more of Finner’s fascinating history by preparing an application for the Community Monuments Fund.

“There is stiff competition nationally for these heritage grants” states Valentine O’Kelly, the Chair of Magh Éne Historical Society, but they are working closely with the Heritage Office, under the guidance and leadership of Dr. Joseph Gallagher, and particularly with the community archaeologist.

From those mighty Bundoran souls of the past who believed in the importance of conserving and preserving local history such as the late Sean Meehan in West End and my own grandad, Dan Keenaghan, in East End – this restorative spirit continues in today’s generation whose families carry that torch-bearing tradition.

From the likes of local historian, Seanie Carty in Fish Lane and the Secretary of Magh Éne Historical Society, Brian Mc Nulty in the Ross – the community is on the right path because conserving Finner Church preserves Bundoran and Magh Éne’s oldest historical building.

A successful application for Finner would first focus on commissioning a Conservation Management Plan. Archaeologist Tamalyn McHugh of Fadó Archaeology, who in recent years worked with the Kilbarron Castle and Church Conservation Group, offered some insight, relaying that this plan includes “historical and archaeological research and a building survey as well as an outline of proposals for conservation.” This research is the key to unlocking Finner’s hidden secrets.

One of Finner’s many intriguing mysteries will determine if Finner Church was built on an even earlier medieval foundation, perhaps even in the time of the sixth century St. Ninnidh. Old natives traditionally believed that Finner was associated with St. Ninnidh.

After studying under St. Finian at Clonard, Donegal-born St. Ninnidh journeyed back up the river Erne from Inishmacsaint to spread the faith. He became the Bishop of Dónach Mor of Magh Éne – the first church apparently founded by St. Patrick in Donegal in the 5th century.

One piece of topographical evidence that may indicate an earlier relationship is the pre-Christian and Christian west-east alignment of Flaherty’s Stone and Finner Church.

I observed this alignment myself many moons ago. Lucky to be the son of former Donegal architect, John Keenaghan, I had access to old maps and even explored the site witnessing the synchronous alignment as I stretched both my arms out after running up to Flaherty’s Stone – setting sun in my left hand and Finner Church in my right hand.

O.S. First edition 6-inch.

The weaving of Celtic-Christian worlds – like a St. Brigid’s cross – at Finner may have begun with the local tribal chief, Flaherty and St. Ninnidh. The late, great Bundoran historian, Fr. Paddy Gallagher in his history book "Where Erne and Drowes Meet the Sea" (1961) stated that “The Saints obtained land from the local chief for a mission church, which was often built inside an enclosed ring-fort, in the traditional style of the time.”

As Finner Church stands today, the ivy-clad ruin encompasses “a two period building." Well-established in the local community prior to the Ulster Plantation, it was recorded as “a chapel of ease” in the Inquisitions of Lifford and Enniskillen in 1609.

The church was later “appropriated and rebuilt;" however, the oldest, western part of the church appears to be a pre-1600 structure. Therefore, the original remains of the Gaelic church that served Magh Éne's faithful may survive.

If Finner Church was originally founded as an early Christian medieval church, then a part of Flaherty and St. Ninnidh’s agreement for this ecclesiastical settlement may have involved protection and respecting ancient Gaelic tradition.

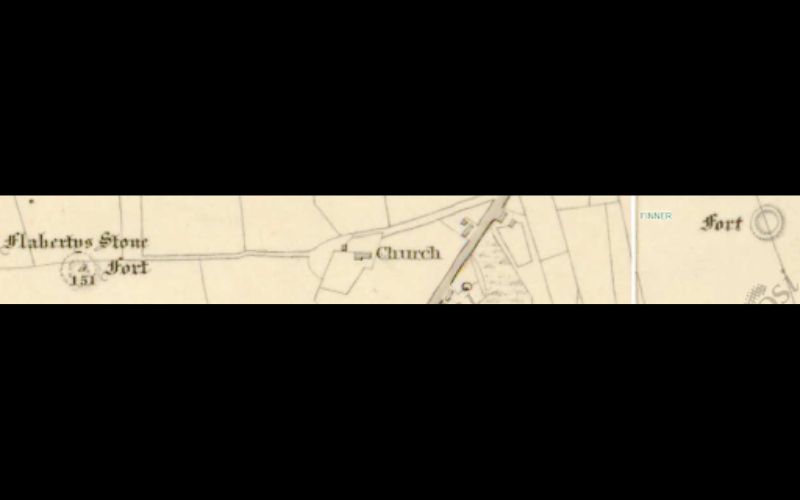

Although the church is not built inside a ring-fort, its west-east foundation lies in between two raths: Finner Hill and Quinn’s Hill. The hospitable chief Flaherty possibly offered protection to the charismatic St. Ninnidh, who, out of respect, built the church in the sacred geometric alignment with Flaherty’s standing stone to earth’s greatest life-giving star – the sun.

Finner Church aligned between two ring-fort raths in O.S. First edition 6-inch.

Could the alignment of Flaherty’s Stone and Finner Church just be a coincidence? Or could the remnant of the aligned path provide interpretative evidence of pre-Christian and Christian worlds – a sign of celestial design?

It's a recognised historical fact that many early Christian saints and their stone-masons built their churches around earlier pre-Christian areas in Ireland. Considering that the standing stone and church are clearly aligned is persuasive enough, yet what is more compelling is that they are also additionally aligned with the westernmost point of Rougey’s Aughris Head and orientated west-east to the setting and rising of the sun.

This alignment is partly evident in this aerial photograph from Historical Bundoran, curated by Donegal journalist and Bundoran native, Michael McHugh.

This alignment of Celtic-Christian worlds at Finner is the start of an exciting adventure for Magh Éne Historical Society and especially for those in the local community whose ancestors and family are buried in Finner Graveyard. The memories and stories of those souls are a vital part of that history.

From Left (West) to Right (East): Aughris Head, Flaherty’s Stone on Finner Hill and Finner Church (in Ruins)

For my own family, I’ll share a brief story of my grandad, Dan Keenaghan’s father, Jack Keenaghan (1882-1960), who was a Ganger for the Donegal County Council. Jack’s great grandad, John Keenaghan (1770-1869) was one of the locals who translated the place name ‘Finner’ from Irish into English in 1835 at the time of the first Ordnance Survey Map. He is noted as the “Mr. Keenaghan,” an Historical Reference on Logainm.

Mr. John Keenaghan was a farmer and hedge schoolmaster, the grandfather of Master Peter Keenaghan (1847-1919), Schoolmaster of the Rock of Bundoran National School (1868-1892) and Behey National School (1893-1912).

The true etymology of ‘Finner’ varies widely, but I personally treasure my great-great-great-great grandad's translation of ‘Fionnmhuir’ (Finner) meaning “Fair or Bright Sea.” As an old local native and gaeilgeoir from Rathmore, he possessed an intimate familiarity with the land and language compared to some of the other translators.

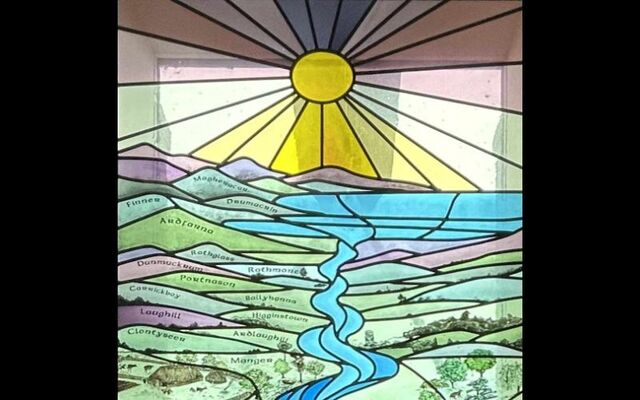

Finner’s translation “Fair or Bright Sea” also evokes the inspiring image of Bundoran’s other name, “Réalt na Mara” – Star of the Sea.

My Grandad Dan Keenaghan standing by the old Keenaghan Grave in Finner. He sculpted the white cross. The grave was beautifully redone/ several years ago by my Uncle Daniel Keenaghan.

These Celtic-Christian alignments appear not only at Finner in Bundoran, but also throughout Ireland.

No matter if you’re from Donegal, Kerry, Galway, Dublin, Fermanagh or Offaly – every Irish person at home and abroad has the opportunity to explore these old ordnance survey maps and discover these Celtic-Christian landscapes that may be connected to the stars on the Historic Environment Viewer.

As Finner’s dawning and setting sunlight passes over the enlightened plain of Magh Éne and shines brightly crossing Réalt na Mara – Star of the Sea – could the starry alignment of Flaherty’s Stone and Finner Church illuminate us to Ireland’s Celestial Celtic-Christianity?

*Éamon Ó Caoineachán (Eddie Keenaghan) is a poet and writer, originally from Co Donegal, but now living on the Gulf Coast of Texas. He is currently a PhD postgraduate in Arts at Mary Immaculate College in Limerick.

Comments