| David McCullough |

It was an odd Fourth of July weekend.

First, you had the interesting news out of Rhode Island that Governor Lincoln Chafee had officially pardoned an Irish immigrant who was hanged for murder in 1845, after a highly questionable trial took place in an atmosphere charged with anti-Irish, anti-Catholic sentiment.

For a history buff such as myself, there is value in this. We should do our best to acknowledge and correct the mistakes of the past. That was certainly done in this case.We should also, however, use the past to guide us in the present.

And while anti-immigrant sentiment today is not the kind we saw in Rhode Island in 1845, I would say we are still in a rush to imprison certain kinds of people, and in no rush whatsoever to ask tough questions about how they ended up there.

But okay, that’s nitpicking. More depressing is the story that refuses to go away, that of Fox Business channel commentator Eric Bolling, who has been accused of making racist comments, in part because he said President Obama was “chugging 40s in Ireland,” rather than returning to America to help tornado-ravaged regions of the Midwest.

Much attention has been paid to the possible racism in this statement, but what about the automatic link to the Irish and drinking! Then again, what can you do when the most common photo of Obama in Ireland is one of him hoisting a pint?

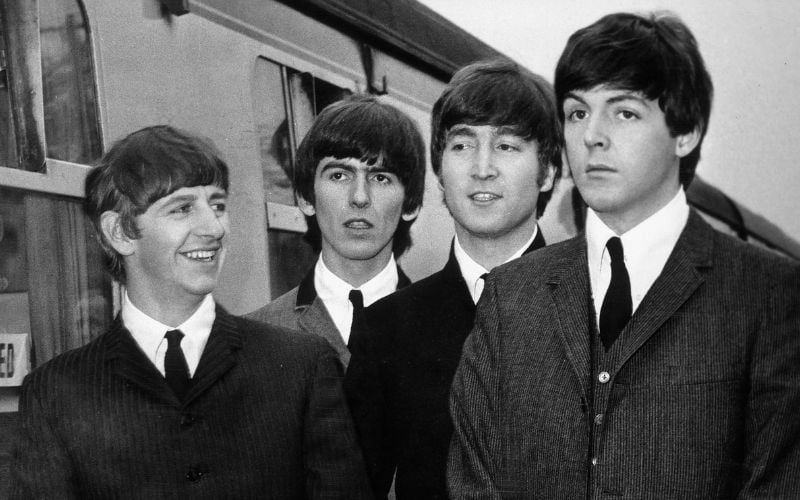

If you’re like me and want to momentarily forget about some of this surreal stuff, you may want to pick up a copy of historian David McCullough’s new book. In The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris, McCullough (best-selling author of Truman) tells a forgotten story about an inspiring Irish American whose name not many people remember, yet whose work we see all the time.

His name was George P.A. Healy. His father was an Irish-born captain in the merchant marine. The oldest of five children, Healy grew up poor in 1820s Boston. He aspired to be an artist, however, and he is one of many Americans McCullough explores who went to Paris in the 1830s to soak up the culture of that city.

“For a much younger, still struggling and little-known artist like George P.A. Healy of Boston, Paris was even more the promised land. He was the oldest of the five children of a Catholic father and Protestant mother. Because his father, a sea captain, had difficulty making ends meet, he had been his mother’s ‘right hand man’ through boyhood, helping any way he could.”

Healy, though, emerged from boyhood with a passion for art. In 1834, he went to Paris to see sites that most Americans – mush less a poor Irish kid from Boston – would never have seen. Centuries-old buildings, classical works of art, even museums were unheard of in the United States.

Healy would go on to become best known for his portraits of American statesmen, including a famous portrait of the peacemakers settling the terms of the U.S. Civil War, and of Abraham Lincoln himself. One of Healey’s portraits of Lincoln became a famous stamp in the 1950s.

Healy was joined by at least two other artists of note with links to Irish America. First there was Augustus Saint Gaudens. Though his name is decidedly non-Irish, Augustus was born in Dublin in 1848 to a French father and Irish mother.

He moved as a youngster to New York City and would go on to become one of the premier sculptors of his day. He is perhaps best known for his works commemorating famous figures from the American Civil War as well as the statue of Parnell on Dublin’s O’Connell Street.

Given the state of stories floating around the world these days, about chugging forties and things of that nature, I found the Healy story in McCullough’s book particularly inspiring on Independence Day. But even this book has its depressing side.

One other painter of note who went to Paris around this time was Samuel Morse. Most people, these days, remember Morse for the telegraph he invented and the code that was used to convey messages on this miracle machine of its day.

Morse was also a great painter. But guess what? Morse was a rabid anti-Catholic and opponent of immigration.

Presumably, he shed no tears when that Irishman was hanged in Rhode Island way back in 1845.

Comments