'Tis the season for ghosts, goblins, and ghouls. None is more ghoulish than Dracula—an undead foreign aristocrat whose bloodline is multiracial and whose appetite for blood not only keeps him youthful and energetic but also infects those whom he bleeds for sustenance. Dracula, it could be said, is a bloodthirsty colonizer.

There are many interpretations of the 1897 novel by Dublin-born Bram Stoker. Most will mention where his parents hailed from, his life experiences, the Irish Famine, and the mythology of Ireland that influenced his writings.

Few, however, dive into the connection between the novel and colonization.

Let's revisit some of the influences we already know before diving into that.

Irish Folklore and Myth

Much has been written about the Abhartach of Irish myth as the model for Stoker's vampire. Folklorist Owen Harding believes that even the word Dracula comes from the Irish words for tainted blood, dreach-fhoula. Sometimes, the myth has this blood-drinking "neamh-mairbh" (walking dead) dwarf, the Abhartach, as being killed twice by a chieftain called O'Kane, only to discover that the creature keeps coming back from the grave. Eventually, on the advice of another chieftain, O'Kane kills the creature a third time and buries it upside down.

Retired Ulster University professor Bob Curran has an added feature to the death of the Abhartach. Curran tells Robin Sheeran of BBC NI, "In the end, the tyrant was run through with a sword of yew wood and buried upside down." The myth was well-known in Irish literary circles, according to Curran. Harding, too, says there was indeed a manuscript of this myth on public display. According to Harding, the manuscript was called The Abhartach, Dreach-Fhoula. It was displayed in 1868 at Trinity College Dublin, where Stoker was a student between 1864 and 1870.

Victorian Repression

Some readers view the novel as representing a repressed Victorian Society sexually, morally, and financially. Strict Victorian morals straitjacketed men and women. Jack the Ripper, the Whitechapel serial murderer of women, had killed and dismembered at least five women in London's lower East End between August and November of 1888. His victims, often presumed to be prostitutes, were women who had low-paying jobs but, being financially strapped, occasionally turned to sex work. Their murders are notoriously documented in the headlines of the period. There's no doubt Bram Stoker was reading those headlines.

Genius for Research

According to Daniel Farson, author of The Man Who Wrote Dracula: The Biography of Bram Stoker, Stoker was a "genius for research." This sentiment was echoed in a Time article by Stoker's great-grand-nephew Dacre Stoker and J.D. Barker on October 3, 2018.

Bram Stoker's visit to Whitby in the summer of 1890 resulted in extensive research that made its way into the published novel by requesting a little-known book, The Accounts of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. A brief visit to the Whitby Museum was made to view maps of London with routes to a mountain deep in Romania. From there, Stoker went to Whitby Harbor and learned from members of the Royal Coast Guard that a ship called the Dmitri had run aground offshore. A mysterious black dog escaped from the hull of the vessel. Even more curious is the cargo; while investigating the damaged ship, which had originated from a port in Varna, rescue workers discovered crates of earth. All of this sounds very familiar to fans of the novel.

Disease and fear of catching disease were also making the headlines. A plague, which began in Yunnan, China, in 1855, would spread to every continent by 1880. The expansion of empires, the invention of new transport, such as trains, and a rush to grab valuable resources, specifically copper in China's case, sped up the spread of disease along trade routes.

Indeed, Dublin Castle and Stoker's time as a civil servant there have caused some to reflect on the possibility that Dublin Castle is Dracula's Castle and the trapped Jonathan Harker is the trapped civil servant, Bram Stoker. While working in Dublin Castle, Stoker satisfied his yearning to write, becoming the theater critic for the Dublin Evening Mail, then co-owned by one of my favorite Gothic writers, Sheridan Le Fanu.

Stoker's Mother was a Writer

Most Stoker fans know that his mother was from Co Sligo and his father was from Co Derry. They were friends with Oscar Wilde's parents and would attend salons at the Wilde's house. Few people know Bram Stoker's mother, Charlotte Blake, was also a writer. "Charlotte lived through the Sligo cholera epidemic of 1832. She wrote a credible account describing the disease, which killed around 1,500 people in the small town in less than two months. She explained how people at that time believed cholera came from the sea and traveled overland like a mist, just like her son would later write of Count Dracula," says Marion McGarry of RTÉ's Brainstorm.

The Ireland Before You Die team adds another vital feature from Charlotte Blake's essay. "Charlotte's family were Church of Ireland Protestants, but in her essay, a strange hero emerged in the form of the local Catholic clergy who seemed immune to the disease while continuing to tend to victims. One priest physically protected cholera patients from the staff at the local infirmary armed with a horsewhip."

RedStorm1368, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

British Empire and Rapid Change

The novel itself could be interpreted as a metaphor for reverse colonization. Stephen Arata, author of The Occidental Tourist: Dracula and the Anxiety of Reverse Colonization, says, "Dracula enacts the period's most important and pervasive narrative of decline, a narrative of reverse colonization."

The writing genre of the late Victorian period is dense with societal anxiety. Fear of rapid change, as depicted in H.G. Wells's The Time Machine, was published in 1895, only four years earlier than Stoker's Dracula. Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness was published two years later, in 1899. It, too, is filled with anxiety in the form of punishment by illness and death for invading and destroying native lands and native peoples.

Given that Bram Stoker was a "genius researcher," this awareness of rapid change and retribution for the British empire's expansion hardly escaped Stoker's conscience. In fact, according to Arata, "A concern with questions of empire and colonization can be found in nearly all of Stoker's fiction." But what are these metaphors that are subtle reminders of reverse colonization?

How can we know that the novel shows Count Dracula as the epitome of reverse colonization? First, the year Dracula was published was a Jubilee year.

"One marked by considerably more introspection and less self-congratulation than the celebration of a decade earlier," says Arata. Decay of global influence, loss of overseas markets, the economic and political rise of Germany and the United States, growing unrest in British colonies and possession, and increasing domestic uneasiness over what Arata calls "the mortality of imperialism- all combined to erode Victorian confidence in the inevitability of British progress and hegemony." These anxieties are, according to Arata, "responses to cultural guilt."

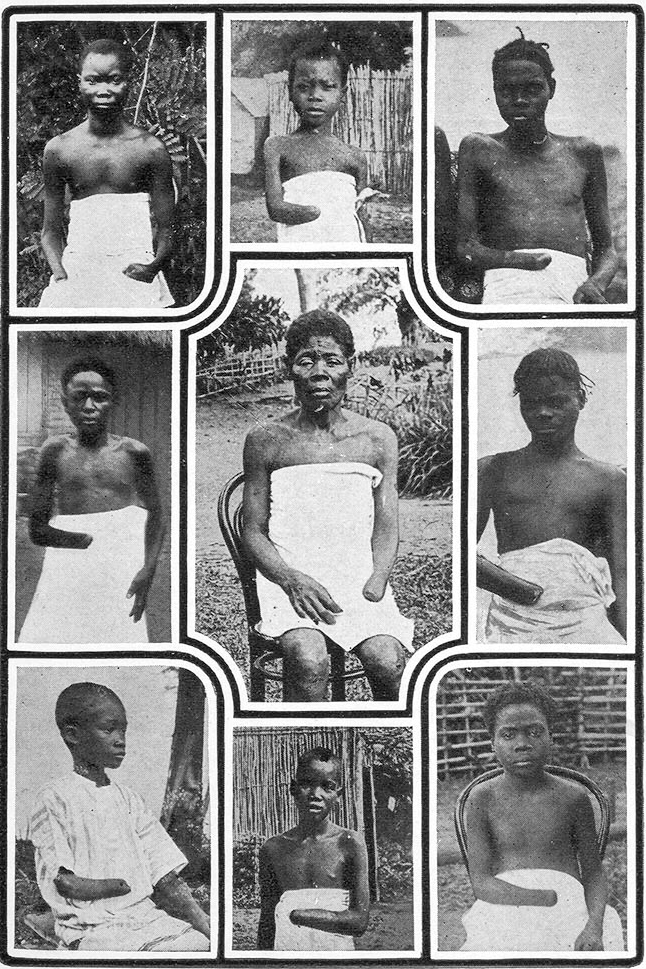

By Unknown author - here, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=99052792

The novel Dracula has a peculiar narrative style for modern readers: told through letters, diary entries, and medical journal entries, the book hits all the marks for the Victorian period. The travelogue was a prevalent genre. Jonathan Harker travels from London via boat and train deep into the Carpathian Mountains. His journal entries and letters to his beloved Mina note the difference between landscape and people.

Despite prior research about Transylvania, Harker is an uneasy foreigner in a strange land. His host, Count Dracula, however, surprises him. Harker writes: "In the library I found, to my great delight, a vast number of English books, … of the most varied kind - history, geography, politics, political economy, botany, geology, law - all relating to England and English life and customs and manners"

Count Dracula tells Harker, "'These friends (the books) .. have been good friends to me, and for some years past, ever since I had the idea of going to London, have given me many, many hours of pleasure. Through them, I have come to know your great England." If Harker has done his research, Dracula has, too. But the Count's research sounds more like an invasion prep than a travel guide.

Harker's surprise at the educated and well-stacked library shelves of Dracula's castle seems to paint him in a strange light. Is he the educated Englishman looking down on a native? It's possible.

In Stoker's time, the scramble for Africa was at the forefront of British ambitions. Along with France, Spain, Belgium, Italy, and Portugal, the dark continent held untold riches waiting to be exported and exploited. The only thing that stood in the way of diamonds, coal, rubber, timber, and ivory were native people. The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 created rules restricting colonizers in Africa.

Five years after the conference, two instrumental men were in Central Africa on research expeditions. Joseph Conrad met Roger Casement in Congo in 1890. Both men would later write about the "great lie of colonialism" as per The Dream of the Celt author Mario Vargas Llosa. Roger Casement was knighted in 1905 for his Congo work and stripped of the title in 1916 for his involvement in the 1916 Rising. Bram Stoker would have been aware of the writings of both men.

He would also have been very much aware of the leader of the Home Rule Party, Charles Stewart Parnell. In 1885, Punch magazine depicted Parnell as a vampire bat. According to Ireland Before You Die, Bram Stoker supported Home Rule.

The salacious headlines involving Parnell and Katherine O'Shea's affair shocked sensible Victorian attitudes. We all know her as "Kitty" because this was a slang term for a prostitute.

Dracula and Reverse Colonization

Multi-ethnic

Unlike the English, Dracula is of many races due to multiple invasions of Transylvania. According to Dr. Van Helsing, "He has followed the wake of the berserker Icelander, the devil-begotten Hun, the Slav, the Saxon, the Magyar." Unlike elite Englishmen, Count Dracula cannot trace his bloodlines to one distinguished ancestor, and many warrior races pollute his bloodline.

Master of Disguise

Twice in the novel, Count Dracula wears Jonathan Harker's clothes and disguises himself as his guest. According to Arata, "The equivalence between these two sets of actions is underlined by the reaction of the townspeople, who have no trouble believing that it really is Harker, the visiting Englishman, who is stealing their goods, their money, their children. The peasant woman's anguished cry - "Monster, give me my child!" - is directed at him, not Dracula."

Sounding English

However, looking like an Englishman isn't enough for Count Dracula; he must sound like one too. When Harker compliments the Count on his proficiency in the English language, Dracula responds, "Well I know that, did I move and speak in your London, none there are who would not know me for a stranger. That is not enough for me. Here I am noble ... I am master ....

"[In London] I am content if I am like the rest, so that no man stops if he sees me, or pause in his speaking if he hear my words, to say 'Ha, ha! a stranger!' I have been so long master that I would be master still - or at least that none other should be master of me."

We are left to understand that dressing and speaking like an Englishman will permit Count Dracula to be a master of the English.

Religious Symbols

Dracula's aversion to holy water, communion wafers, and the crucifix are not only connected to the Catholic Religion but also the Anglican. According to historian Noelle Bowles, these images formerly were thought to represent "Stoker's attempt to reconcile the interfaith conflicts of his native Ireland, the author's effort to reinforce the Protestant Ascendancy through colonization of faith, or even, and absurdly, a novel of proselytization through which Stoker seeks to convert his Protestant readership to Catholicism."

Bowles believes that Stoker's faith, Anglican, should be considered. Harker arrives at Count Dracula's castle on the eve of St. George's Day—the patron saint of England who slays a dragon. Harker, too, will kill Count Dracula. Let's remember that Dracula, the character, is often connected with Vlad the Impaler of Romania. Regarded as a national hero there, Vlad was a bloodthirsty prince inclined to impale his foes. Leonie O'Hara of Ireland of the Welcomes states, "The name Dracula comes from Drac, the name of Vlad's father. Dracula simply means son of Drac, which means devil, or it may mean dragon."

William Hughes, author of Bram Stoker: Dracula- A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism, addresses contradictions within the Anglican community rather than addressing the disagreement between Catholicism and Protestantism. In 1855, the Liddell Judgement rejected the use of the crucifix in the Anglican Church because it had been "abused." Dr. Lushington of the 1855 Consistory Court declared, "It might be abused again by superstitious notions." Religious symbolism in the novel is used to ward off the evil that is Dracula. But it is the symbolic action of drinking blood that is both Catholic and supernatural.

When Count Dracula tries to infect and thus colonize Mina by making her drink his blood, he says, "And you, their best beloved one, are now to me, flesh of my flesh; blood of my blood, kin of my kin…" If these words sound familiar, it is because, during a Catholic mass at the consecration of the Eucharist, the priest will say, "This is my body," or "This is my blood," or "This is the chalice of my blood." When Dracula speaks the words above, we have the colonization of religion and person. It is what Catherine Wynne calls "a physical and sexual mastery" of Mina, where Dracula "gains a psychological possession of her." Would Victorians have been shocked at this? You bet.

Throwing holy water, communion wafers, and holding up a crucifix repels Count Dracula and his minions, but when he bites you, you're colonized and become a colonizer for him. When you drink his blood, the same thing happens. So, the symbols of the crucifix, communion wafers, and holy water may represent conflicts within the Anglican church. Still, blood-drinking seems to represent infection, submission, and colonization.

Reflection of the Colonizer

When Jonathan Harker looks for Count Dracula's reflection in the mirror, he sees only himself. "This time there could be no error, for the man was close to me, and I could see him over my shoulder," Harker says in the novel. "The whole room behind me was displayed; but there was no sign of a man in it, except myself." This, says Carol Senf, author of Dracula: The Unseen Face in the Mirror, is Stoker illustrating his character's lack "of moral vision."

"Harker's inability to "see" Dracula," Senf says, "is a manifestation of moral blindness which reveals his insensitivity to others." There are numerous pictures of the atrocities carried out during the scramble for Africa in which punishment delved out on native peoples by the colonizers shows this insensitivity. The inability to see natives as fellow human beings resulted in hands being cut off, food being withheld, and other brutalities.

Yet, Harker remains unafraid until he learns Count Dracula will return to London with him. According to Senf, Harker's response "indicates that he fears a kind of reverse imperialism, the threat of the primitive trying to colonize the civilized world."

Jonathan Harker tells us in the novel, "This was the being I was helping to transfer to London, where, perhaps for centuries to come, he might, amongst its teeming millions, satiate his lust for blood, and create a new and ever widening circle of semi-demons to batten on the helpless."

Arata agrees with Senf's conclusion. "The late-Victorian nightmare of reverse colonization is expressed succinctly here: Harker envisions semi-demons spreading through the realm, colonizing bodies and land indiscriminately."

The Real Horror of Colonization: Photo by Alice Harris, Daniel Jacob Danielsen

Traveling with Earth from the Homeland

The trip to Whitby in the summer of 1890 may have inspired Stoker's use of a coffin filled with earth to sustain Dracula's journey to England. However, the connection of bringing the homeland with you isn't too far of a stretch. Wherever the colonizers went, they tried to create England abroad. From Ireland to Australia, Canada, India, and America, this idea of creating a home away from home turned the colonies of the British Empire into mini replicas of English life. From buildings to customs to the recreation of entire Victorian villages, see Cape May in New Jersey, this notion that the English way of life was the best way of life has shaped the world from 1450 until today.

In 2015, Adam Taylor of the Washington Post wrote The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. In it, he uses a map depicting the growth of the empire until 1919, when it shrinks back. Most places highly influenced by English culture, architecture, and societal norms are, no surprise, ports. These are places where trade occurred and valuable resources shipped abroad. Again, we return to an odd event in the novel Dracula—he bleeds gold coins.

As per Arata, "Harker cuts Dracula with his knife, he "bleeds" a "stream of gold" coins." Is this Stoker's idea of blood money?

Dracula: Colonized or Colonizer

Although we shall never know for sure if Bram Stoker was indeed hinting at the evils of colonization in his now-famous novel, the breadcrumbs are there to suggest it. He was born in 1847 and would have been exposed to tales later in life of the horrors of the Irish Famine: people being buried alive, survivor cannibalism, and the spread of infectious disease.

Stoker would have also been aware of conflicts within his Anglican religion, the push for Home Rule, and the scramble for Africa in later life. What is difficult to understand is how exposure to the knowledge of all of these things could not have influenced his writing in some way.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments