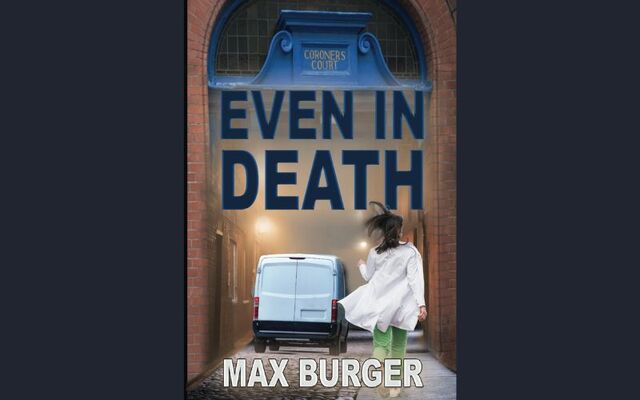

In Max Burger's "Even in Death," we follow the tale of Harold Stokes ME in the aftermath of a car bomb in 1970s Dublin leaving 26 bodies, until one is stolen.

The following is an extract entitled "The Student's Story":

As Professor Stokes stood at the podium, he looked at the fresh young faces and thought again about his daughter, her enthusiasm for learning and her plans, before she died, to start Medical School that fall. All blown away that early morning in the theatre in Dublin.

He gave his lecture as an introduction to the students on the need for them to learn everything they could about anatomy, physiology, and chemistry, which were the tools they would need to get to forensic pathology. He gave them some examples of cases he had reported (he never considered he was an investigator since he merely observed and reported) but there was enough of the morbid thrill of crimes and detection in the details that encouraged if not titillated the students, like the curious case of the girl in the bathtub or the accidental suicide, which always got their attention. He was well beyond titillation. It was a job he considered with respect and gravitas.

“Never consider your position as a physician in this or any field you choose without remembering that these are people whose lives meant something to them and their loved ones,” he always concluded at the end of the lecture. They all streamed out except for one sad-looking student who, he expected, would need to talk.

“I was there in the operating theater when they brought one of the casualties in. I was wondering if you knew how he died,” the young man asked.

“What year are you in?” Stokes asked.

“First clinicals, sir, I was assigned to St. Laurence,” he replied.

“Tell me the history so that I can try to determine whom you are speaking about,” Stokes asked.

Read more

He paused for a moment and then began, nervous in front of the Professor and anxious to tell the story. He was afraid he might miss some essential details: “When the bombs went off, some of us were napping, waiting for tea. Then we heard the thumps like heavy boots being dropped on the floor above. No one had thought what they might be. Some didn’t even hear.

"But we all heard the sirens. They didn’t take long in coming. Soon the sirens were around us and we ran to Casualty to see. We could hardly get in for all the ambulances crowded at the door. Inside was a shambles—there were people lying all around, some on stretchers, some on the floor, some screaming, some quietly moaning. All the doctors were there, trying desperately with the nurses to make some order. The Chief Surgical Registrar was going from bed to bed, triaging. He barked commands like a Captain. He had been a surgeon with the British in Aden.

"One nursing student, short and fat, ran back and forth— she didn’t know what to do, and she was crying. The Registrar sat her down and said shut up. She did.

"We helped with the man whose heart stopped. He must have been about 30—looked like a worker, big and strong. His heart had stopped, but they got it going again. We took him to the operating theater. He had lost a lot of blood. Some of us stood at his head, others at his stomach, others at his feet.

"Mr. Clary opened his belly to find the site of the bleeding and look for fragments of shrapnel from the car. There were none, but there was a hole in his aorta, a nick in the celiac artery, and his bowel. He kept on bleeding —he’d taken 10 pints of blood when someone said “Turn him over, for bloody sake.” There was a gaping hole in his backside–with still more bleeding. They had him on his side long enough to clamp and tie the bleeding vessels. Then they turned him back to keep fixing his bowel. His heart stopped again and Grayson, the senior registrar, announced it loudly. He yelled for them to start pumping, but Clary yelled back that he had his bloody heart in his bloody fist and that he was pumping from under the diaphragm. Again, the man’s heart worked.

"No one knew who he was. He had a black rose tattooed on his right arm. His wounds were from the front and not the back as if he had not been running away. I said out loud what we all thought. Maybe he was the car bomber—the one who had left the bombs. Maybe he had been caught himself. We all stopped. Everyone looked at each other over their masks, eyes glaring down. How would you treat a killer? We were angry. We had seen what a bomb could do. Who was this man? We never found out. He died.”

Read more

Stokes stood there for a moment and then put his arm on the student. He was young and this was probably the first casualty he had ever seen. There was no easy way to comfort him but with the facts.

“I know exactly who you described. He died of gunshot wounds. The investigation is ongoing, so I can’t say more, but there was nothing in the world that anyone could have done. The damage was extensive and the wounds were fatal, but your description of the events may be helpful in the investigation. Remember what you saw. Use it to learn from and try to help others more fortunate in the future,” Stokes said reassuringly, placing his hand on his shoulder.

“Thank you, sir,” the student replied and turned to go. Stokes just stood there for a moment, recalling his own first experience of the death of a patient and how helpless and overwhelmed he had felt by the loss and his sympathy for the patient. Stokes had listened and explained so that this young man would not blame himself; he was only a passing participant. Stokes hoped that his encouragement of the student’s testimony and his sympathy could help the student’s future career.

Even after all these years, Stokes still felt guilty that he had not done enough when he left the bed or the examination of a deceased patient. He would go home to study the circumstances and causes of the condition that had killed him to give that death more purpose and teach him some lessons. It was like seeing a horrible movie and then reading the book, the words now illustrated more graphically. He would always remember the case. We always remember best by feeling, he noted. That student will recall that incident for the rest of his life, he predicted.

*This is an excerpt from the novel "Even In Death" by Max Burger available here.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments