Review of “Lincoln and the Irish: The Untold Story of How the Irish Helped Abraham Lincoln Save the Union” by Niall O’Dowd.

When someone, anyone, has already been the subject of 15,000 books, does the republic of letters need yet another one?

In the case of Niall O’Dowd’s just published “Lincoln and the Irish” (Skyhorse Publishing) the answer is an exclamatory yes. Though relatively short and occasionally somewhat repetitive, O’Dowd’s book is much more than a study of America’s 16th—and most revered—president. It is also a fascinating tableau of significant, sometimes unsung, Irish Americans and their contributions to U.S. history when the fate of the Union was very much in doubt.

“Honest Abe” was inaugurated on March 4, 1861, and he died from an assassin’s bullet early on April 15, 1865. The Civil War began with the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina on April 12, 1861 and continued at full tilt until Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. By comparing those dates, it means that Lincoln served just 45 days without the nearly unbearable burden that comes from the savagery and sorrow that claimed over 600,000 lives.

Cover art for "Lincoln and the Irish".

Throughout Lincoln’s presidency and earlier in his political career— O’Dowd convincingly shows—many Irish men and women helped the “Illinois Rail Splitter” turned “Great Emancipator.” Unlike so many Americans of the time who regarded the influx of emigrants from famine-ravaged Ireland as a pernicious demographic blight, Lincoln thought otherwise. His Celtic fondness even prompted grumbling complaints “that he was surrounded by a Hibernian clique.”

Lincoln’s humanity and magnanimity are on display throughout this book. He’s determined to save the Union and to free the slaves, but he’s always reaching out with kindness in almost every direction.

O’Dowd makes clear that Lincoln looked beyond demeaning, anti-Irish stereotypes (which his wife and closest friends failed to do) and cultivated an “innate concern for all underdogs.” This trait leads the author to a question that’s more rhetorical than in need of an answer: “Why else would his domestic staff both in Springfield and in the White House be composed of so many Irish immigrants?”

Read more: 55 years ago JFK followed the path of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg

Politically, of course, the American Irish of the mid-19th century felt more at home in the Democratic Party than either Lincoln’s Republican Party or the virulently anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic Know Nothings of the American Party, influential with some Republicans. But Lincoln’s cause was paramount, and the Irish knew his mettle.

Indeed, in a letter he wrote in 1855 he came out foursquare against Know Nothingness and what it represented with admirable force and clarity: “How can anyone who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we begin by declaring that ‘all men are created equal, except negroes.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except negroes.’ When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and Catholics.’”

Given Lincoln’s largeness of spirit, it’s intriguing to imagine what he would have been like as a national leader without the Civil War to haunt his nights and days. But, as he solemnly noted in his second inaugural address, “the war came.”

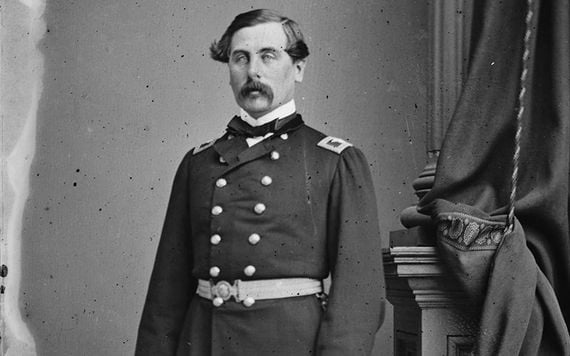

O’Dowd singles out Thomas Francis Meagher, Archbishop John Hughes and Michael Corcoran—all Irish born and acquainted with Lincoln—as key individuals who “forged the path for 150,000 Irishmen to fight and very likely save the Union.” Besides this heroic trinity, General Philip Sheridan “arguably was the hammer on the anvil that brought the war to an end.”

Thomas Francis Meagher.

Each of these figures receives thorough treatment, but the book is enhanced with the tales of derring-do from lesser known men and women of Irish heritage. Take, for example, Jennie Hodgers from Clogherhead, County Louth.

Hodgers, we learn, became “Albert Cashier” and volunteered to fight in the 95th Infantry Illinois, one of the “estimated 400 women” who fought as male soldiers in the Civil War. In this particular case, Cashier spent the rest of his life as a man, a change of identity that began when Hodgers sailed in manly garb as a stowaway to America from Ireland.

O’Dowd explains a coincidence of Catholic clerics during the Civil War that, in its way, is jaw-dropping. Lincoln summoned New York Archbishop (“Dagger John”) Hughes to the White House and sent him on an eight-month European tour, including the Vatican, as a presidential emissary to advance the Northern side in the war. At about the same time, Confederate President Jefferson Davis met with Rev. John Bannon and asked him to sail “to Ireland to block the recruitment of Irish” to the Union army and also to visit Pope Pius IX. Though Davis and Bannon wanted papal support of the South, that wasn’t forthcoming.

New York Archbishop (“Dagger John”) Hughes.

O’Dowd’s knowledge of Lincoln and the Civil War is vast, and he brings out in bold relief Irish involvement at every level of White House and wartime activity. The book’s subtitle—“The Untold Story of How the Irish Helped Abraham Lincoln Save the Union”—deftly captures what the author sets out to do, though more direct reference to the historical sources might help a reader pursue more aspects of this neglected dimension of the subject.

Near the end of his book, O’Dowd states: “Lincoln’s embrace of the despised Irish should never be overlooked, nor their role in helping him win one of the most important conflicts of all times, which, with a different outcome, would have transformed the world we live in even today.”

About a much different and more distant time, Thomas Cahill wrote “How the Irish Saved Civilization.” Closer to home and to 2018, O’Dowd’s new book makes the case that the Irish in America were vitally important to the continuation of the relatively new nation Lincoln judged to be “the last best hope of earth.” That is a story none of us should ever forget.

* Robert Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Chair in American Studies and Journalism at the University of Notre Dame. He’s the author of “Ireland’s Exiled Children: America and the Easter Rising” (Oxford University Press) and “Fifty Years with Father Hesburgh: On and Off the Record” (Notre Dame Press), both published in 2016.

Comments