The contribution of the Irish to American society and culture is profound, from Scott Fitzgerald in literature, George M. Cohan in music, James Cagney in films, the Kennedys in politics - the list is long and impressive.

In sport, which ranks high in America, the Irish dominated boxing during the early years of the twentieth century, particularly the heavyweight divisions where seven of the first titleholders were of Irish descent.

But where the Irish impact was the greatest and most profound was in the emerging sport of baseball, known as “America’s game.”

Baseball grew up with America. Various versions of the game were imported from England and one form called Town Ball, where a batted ball was hit and the batter ran to bases, was the most likely progenitor of America’s version of a bat and ball game.

Baseball first took root in a recognizable form in the 1840s when various men, particularly Alexander Cartwright of the New York Knickerbocker club, over a period of years began systematizing the rules, i.e., the diamond shape, nine players on the field, bases 90 feet part, batted ball out initially if caught on one bounce, eventually caught on the fly.

The new game spread rapidly and by the Civil War, there were over 1000 clubs playing this new sport. In the years following the war, baseball, initially an amateur affair, began to become professionalized especially when it became clear that people would pay to see the game played.

The Irish entered baseball when it became a big-time affair in the 1870s, especially with the founding of the National League of Professional Baseball clubs in 1876. Their reasoning was obvious. Baseball players made good money with salaries by the mid-80s as high as $10,000 for a top player when the average income for workers was around $800 a year.

While doubts have been cast about scope of social mobility in America, baseball did provide an outlet for a minority of young males with athletic talent. This was particularly important for the overwhelmingly Catholic Irish who were despised by large sections of the largely Protestant American public.

But it wasn’t just a financial reward that attracted the Irish Americans to baseball. Unlike cricket, which was widely played in America, baseball had no English connotations. By adopting baseball, the Irish were associating themselves with something believed to be uniquely American.

Irish American players began to appear on major league rosters in growing numbers by the early 1880s. According to Jerrold Casway’s study of what he calls the Emerald Age of Baseball, by 1890, a staggering 40% of the players on major league rosters were of Irish descent.

Three of baseball’s first superstars were Irish, Mike ‘King’ Kelly, a slugging outfielder and sometime catcher, pitcher Tony Mullane, a native of Cork, and perhaps the greatest Irish American baseball player, Ed Delahanty.

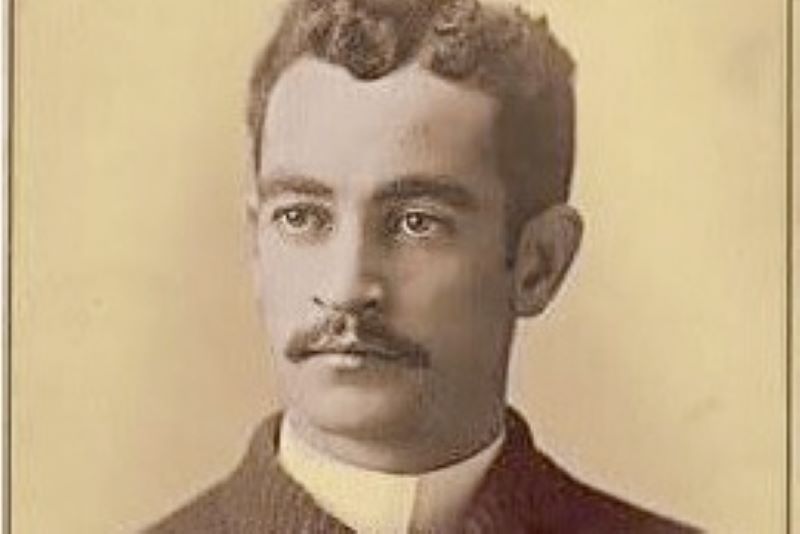

Tony Mullane (Public Domain)

Nicknamed ‘The Count’ or the ‘Appollo of the (pitchers) Box,’ Mullane would go on to win 30 games five times and 285 games during his career. He was popular, especially with the ladies who began to be attracted to baseball as an acceptable sport for women to watch unlike boxing or horse racing, (Ladies Days were adopted throughout baseball in the 1880-1900 period as a way of attracting a new fan base in hopes of softening the rough edges of the game which often featured brawls, gambling, and rough language. It shouldn’t be forgotten that “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” was about a young girl asking her beau to go to a game.)

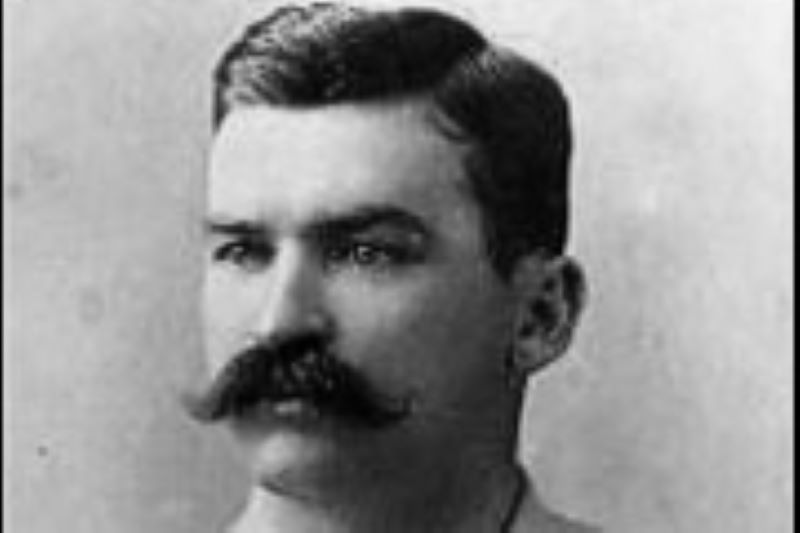

Mike "King" Kelly. (Public Domain)

Kelly was an offensive superstar, a forerunner of the great sluggers like Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron, and Ted Williams who dominated baseball. He was one of the first true gate attractions who drew fans to the game. A colorful figure who not only was a great hitter—he won two batting titles and once hit .385— he also was a daring baserunner who once stole 84 bases in a season. Fans loved his baserunning and would chant “Slide Kelly Slide” when he attempted to steal a base. He is credited with inventing the ‘hook slide,’ heading directly to the base but then throwing his body to the side of the base, tagging it with his toe. At the peak of his career, Kelly was paid the unheard-of salary of $12,000, the equivalent of $350,000 to $400,000 in today’s figures. Unfortunately, he also was characteristic of another quality noted of Irish players—he was a heavy drinker. He died of alcohol abuse at age 36. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1945.

Ed Delahanty. (Public Domain)

The dominant Irish American player of the 1890-1900 era was Ed Delahanty. Nicknamed ‘Big Ed,’ he hit .400 twice, .390 twice, and ended with a career batting average of .346, the fourth-highest in baseball history. Some baseball experts who saw both play rate Delahanty just behind Babe Ruth as one of baseball's greatest offensive players. Unfortunately, along with hitting, Delahanty was a heavy drinker. He died under mysterious circumstances when he was put off a train crossing the Niagara River and fell to his death. Like Mullane and Kelly, Delahanty is a Hall of Famer.

The Irish made the transformation to executive roles in baseball by the 1890s with some like Charles Comiskey, John McGraw, and Connie Mack being owners of baseball teams and in their case, team managers as well. As some gauge of Irish acceptance in baseball, it should be noted that by 1914, 44% of major league team owners were of Irish descent. Even more striking, from 1900 to 1922, fourteen championship baseball teams were guided by Irish managers of whom the greatest were Mack and McGraw who between them won 12 pennants and seven World Series.

A handful of Irish American players in the first two decades of the twentieth century were Hall of Famers including Willie Keeler, a lifetime .345 batter, Johnny Evers of the famous double-play combination, Tinker to Evers to Chance, Ned Hanlon, a successful player and manager, and “Iron Man’ McGinnity, famous for pitching both games of doubleheaders. Two of the best umpires of the 1900-1920 era, Hank O’Day and Tim Hurst, have also been enshrined in the Hall of Fame.

By 1900, the Irish predominance in baseball began to be challenged by other so-called ‘outsiders,’ including a surprising number of Native American players including Albert ‘Chief’ Bender, a Hall of Fame pitcher for the Athletics (almost all Native Americans were called ‘Chief’ in those days), and the most famous American athlete of the time, Jim Thorpe. They were following the Irish in pursuit of acceptance in American society and were attracted to the high salaries they could earn.

For other outsiders such as Jews, Eastern Europeans, Italians, it would take into the 1930s before they would make their impact. Like the Irish, they were attracted by the money to be made and the ultimate acceptance of the dominant groups in American society.

The path that the African Americans and Latin players would follow from Jackie Robinson’s breaking the race barrier in baseball in 1947 had been laid out for them for the despised Irish of the late nineteenth century. Not a bad contribution to American life.

*This article was submitted to IrishCentral by John P. Rossi, Professor Emeritus of History at La Salle University in Philadelphia. His most recent book is Baseball and American Culture: A History, Rowman and Littlefield, 1918. To submit to IrishCentral, sign up for our contributors network IrishCentral Storytellers here.

Read more

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments