Avenge the patriotic gore

That flecked the streets of Baltimore,

And be the battle queen of yore,

Maryland! My Maryland!

---- From “Maryland, My Maryland”

by James Ryder Randall

As Baltimore erupted into riots in April 1861, two of the key figures involved were Irish Americans, and not long after it was over, both of them would be in jail. And both were men of great authority in the metropolis. One, George William Brown, a seconed generation Irish-American, was the mayor, and the other, George Proctor Kane, a first generation Irish-American, was the Marshal (Chief) of Police.

Brown, who was born in Baltimore in 1812, had only taken office in November 1860. His paternal grandfather, who was a doctor, was born in Ireland and immigrated to Baltimore in 1783. George began practicing law in Baltimore in 1839. He rose in city politics by opposing the anti-immigrant Know Nothing Party.

George William Brown.

Kane (below) was born in Baltimore in 1817. Both of his parents were born in Ireland. As a young man he became involved in Whig Party politics. During the years of The Great Hunger in Ireland, he was the president of the Hibernian Society and was active in sending relief. He would also rise to be a colonel in the local militia unit. He dabbled in acting and became part owner of Arnold’s Olympic Theater. An actor who made his debut there was John Wilkes Booth, and it would not be the last time Kane and Booth would be in contact. In February 1860, Kane was appointed Marshal of Police for Baltimore.

George Proctor Kane.

Neither man held his office long before a crisis of unimagined proportions was upon them. In April 1861, as many Southern states were seceding from the Union, the state of Maryland was in turmoil. Maryland was a slave-holding state, and many of its residents were very sympathetic to the South. Lincoln had gotten a mere 2,294 votes in Maryland. Among those sympathizers, as later events would prove, was Marshal Kane.

Mayor Brown, while certainly not a supporter of newly elected President Lincoln, does not appear to have been in favor of secession, though he was surely an opponent of what Lincoln was doing to suppress secession. Baltimore itself was undoubtedly a hotbed of secession sympathizers. Even before the agitation over slavery, Baltimore had such a history of civil disturbances that some knew it as “Mobtown.”

There is no way to get to Washington, D.C. from the north without passing through Maryland, other than a line that passed through Virginia, which was even more problematic. To make matters worse, it was impossible to pass through Baltimore by rail without stopping and changing from one rail line to another. In February, Lincoln had secretly passed through Baltimore at 3:30 am to avoid possible problems. Sneaking through entire regiments of militia units would not be quite as simple.

On April 12th, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, and on the 15th, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers. Maryland had not seceded, but many in the state, and especially in Baltimore, surely supported those who had.

Mayor Brown and Marshal Kane were facing a crisis of conscience. Neither supported Lincoln’s apparent intent to go to war with the Confederate states, but both had a responsibility to uphold the law and to oppose violence. One would hold to that responsibility throughout the crisis, and one would not.

On April 18th, five companies of Pennsylvania militia and a detachment from the 4th U.S. Artillery arrived in Baltimore. They ran into a rock-throwing mob as they made their way through the city to Camden Station. It appears that Kane and his men did their best to protect them. No one was killed on either side, but the mob's blood was up now.

Brown sent a message to Lincoln: "The people are exasperated to the highest degree by the passage of troops, and the citizens are universally decided in the opinion that no more should be ordered to come.”

But it was too late. The 6th Massachusetts was headed to the city and would arrive midday on the 19th (ironically, the anniversary of the Battle of Lexington). The secessionist mob was waiting for them.

When Kane got word the soldiers had arrived at President’s Station around 11 am, he alerted Brown, but he didn’t move any officers in that direction. There was a horse-drawn trolley system to take people from President St. Station to Camden, running most of the way down Pratt Street. So by then, it may have seemed more prudent to guard Camden St. Station, where a considerable mob had assembled, and hope the troops would make the trolley ride safely.

As the train carrying the 6th Massachusetts approached Baltimore, its commanding officer, Colonel Edward F. Jones, had 20 rounds issued to his men. Kane had no officers waiting at the President Street Station, where the troops would arrive. His officers were all with him, waiting at Camden Street Station, a little over a mile away, where the troops had to go afterward to get the train south. The troops arrived at Bolton Street Station the day before, and Kane later claimed not to know their destination on this day, so he waited where he knew they had to go afterward. And it may well be that the Federal government was afraid that if he was given the information, he would pass it on to the people planning to oppose the passage of the soldiers, and his later actions would tend to back up that fear.

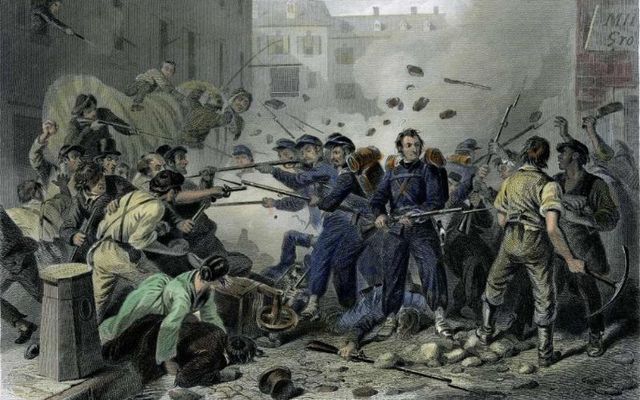

The disaster was very nearly avoided. Most of the regiment made the trip safely, suffering no more than some jeering and a few rocks thrown. But then the mob blocked the rails with a wagon load of sand at Pratt and Gay Streets. The drivers of four of the remaining cars quickly reversed their horses and turned back, but Company K had to leave their cars and move forward on foot.

The riot began in earnest. A pistol was fired from the crowd, and the soldiers, either with or without orders, returned fire.

Meanwhile, Brown left Camden St. Station and arrived at the logjam with some police officers. The mayor joined Captain Follansbee at the head of the company and surely risked his life attempting to stop the violence.

The mayor reported that his presence seemed to mollify the mob, but the violence soon commenced again. Follansbee reported that at one point Brown took a musket from a trooper and shot a rioter, but Brown later denied it. Around the time they reached Charles Street, Kane arrived with a large number of police officers, and they formed a cordon around the soldiers and got them to Camden Street Station without further shooting.

When it was over, four soldiers and 12 civilians were dead, with 36 soldiers and an untold number of civilians, perhaps over 100, injured. The dead soldiers were Luther Ladd, Addison Whitney, Sumner Needham, and Charles Taylor, among the North's first martyrs. Among the dead civilians were several with very Irish-sounding names -- John McCann, John McMahon, Francis Maloney, William Maloney, Philip S. Miles, and Michael Murphy.

Luther Ladd - 17 years old and said to be the first soldier killed

Though Kane had apparently strove to do his duty on the 19th, after the riot, he revealed his true feelings when he telegraphed Bradley Johnson of the Maryland militia, later a general in the Confederate army, saying, "Streets red with Maryland blood, send expresses over the mountains of Maryland and Virginia for the riflemen to come without delay. Fresh hordes will be down on us tomorrow. We will fight them and whip them or die."

The rest of Kane’s life would be quite fascinating. He was arrested in July after martial law was declared in Baltimore and habeas corpus was suspended, no doubt due to his telegraph message. He was held first at Fort McHenry and then transferred to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. He was released in the autumn of 1862 and went to Montreal.

While in Canada, Kane wrote to Confederate President Davis several times proposing different schemes to help the Confederacy, including attacks on U.S. cities along the Great Lakes and the freeing of Confederate prisoners from Federal prisoner-of-war camps, none of which came to fruition. In 1864, Kane was among a group of Confederate leaders in Canada who heard his old acting compatriot, John Wilkes Booth, present a plan for kidnapping Lincoln. It was rejected, but Booth clearly continued to plot against Lincoln.

Kane ran the blockade into Richmond later in 1864 and helped the Confederates in recruiting Marylanders to the cause, as well as helping to provide uniforms for Maryland troops in the Confederate army. After the war, he returned to Baltimore, where he was elected sheriff in 1873, demonstrating that being an ex-rebel was not detrimental to one’s political career in Baltimore. In 1877, that was affirmed again as he was elected mayor. He would not complete his term, as he died June 23, 1878, of Bright's disease, a kidney disorder.

Brown managed to hold onto his office in Baltimore a bit longer than Kane, but in September 1861, even though he did his best to prevent the violence in Baltimore, he too fell victim to the suspension of habeas corpus and was locked up in Fort McHenry. While Kane had blatantly flaunted his loyalty to the Confederacy, Brown had not. Shortly after being arrested, Brown was offered his freedom if he would take the oath of allegiance and resign as mayor, but he refused. He was later transferred to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor, being held in both places with Kane, a friend.

The government continued to offer Brown his freedom with the same conditions, ignoring even the pleading of some members of the 6th Massachusetts on his behalf. But he refused, saying: “I have committed no offense. I want no pardon. When I go out, I want to go out honorably.” He was finally released unconditionally in December 1862, after his term as mayor had expired.

Like Kane, however, Brown's troubles during the war did not impede his political career in Baltimore later. Although he again ran for mayor and lost in 1885, he was a member of the first Board of Trustees of the Peabody Institute, one of the founders of the Maryland Historical Society, a regent of the University of Maryland, a visitor of St. John's College, Annapolis; a trustee of Johns Hopkins University of Maryland; a visitor of St. John's College, Annapolis; and a member of the State Constitutional Convention of 1867. And finally, in October 1872, he was elected chief judge of the Supreme Court of Baltimore City. He died while on vacation with his wife in New York in 1890.

We can agree or disagree with some of their political positions, but both men were true to what they believed until the end of their lives.

(Copyright, 2015, Joseph Gannon thewildgeese.irish)

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments