Only seven years after the Rising of 1798, the Battle of Trafalgar took place.

The British Navy—which was made great, according to one Winston Churchill, by “rum, sodomy and the lash”—led by Lord Admiral Horatio Nelson defeated the combined fleets of the Spaniards and the French. In achieving the great victory, however, Lord Nelson was killed in action. Britain had itself an instant hero!

In a rush to out-do the British, the Irish decided that they needed an erection to honor the martyred Nelson. Poof! Dublin had Nelson’s Pillar.

The foundation stone was laid on February 15, 1808, and the Pillar opened to the public on the anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1809. It was designed by Francis Johnston, who would move across the street and design the General Post Office a few years later.

The Pillar was an architectural marvel, standing 134 feet in height, with 168 steps leading to an observation deck. The 13-foot statue of Nelson was designed by Thomas Kirk. Final cost, £6,299.

By way of proof of the alacrity of the Irish response to Nelson's heroic deeds, the British didn’t get around to building a doppelganger for the Pillar until Nelson’s Column was constructed in London between 1840-43. It stood taller than the Dublin monument at 170 feet. Ironically, unlike its Dublin counterpart, it would survive a dynamite attack by Fenians in the early 1880s.

Dublin's O'Connell Street in 1948 with Nelson's Pillar. (Getty Images)

Suddenly, not so popular

Nelson’s Pillar always had its critics. These criticisms were not so much based on politics or aesthetics, but on commerce because Nelson was stuck up in the middle of Sackville (now O’Connell) Street, separating the Upper and Lower halves, and, some thought, hindering progress for the merchants in the area.

But as the 19th century moved on and Ireland became more nationalistic, people began to question why a British admiral was stuck up in the middle of Dublin’s main thoroughfare. First, there was Daniel O’Connell’s Catholic emancipation in 1829, which was followed by the Young Ireland movement in the 1840s, and finally the Fenian Uprising of 1867.

Early in the 20th century, the Pillar was sandwiched by the Parnell Monument to the north and Daniel O’Connell’s statue to the south. Nelson now looked even more out of place stuck between two iconic Irish patriots.

By the turn of the 20th century, Nelson was a relic of another Ireland. And the criticism began to come from prominent Irishmen. James Joyce in "Ulysses" referred to Nelson as a “one-handled adulterer.” James Connolly thought it “a terrible eyesore.” Yeats, although a supporter of the Pillar, admitted that “…it is not a beautiful object.”

By mid-century, all the niceties had been deleted. Brendan Behan didn’t hold anything back: “The one-armed, one-eyed Admiral of the British-bollock-shop institution the Royal Navy has no business in his perch at all. He has no fucking place in Ireland’s history but a wrong one.”

After the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922, many questioned why the Admiral should be up there at all. “Save the Pillar, but remove Nelson” seemed to be the battle cry.

Replacement statues were nominated, with whiplash effect: The Blessed Virgin Mary, Padraig Pearse, JFK, Wolfe Tone, St. Patrick, Robert Emmet, James Connolly, and James Larkin. Somehow, Jesus Christ himself didn’t make the cut. Even Mike Quill, ex-IRA man and head of New York City’s Transport Workers’ Union, volunteered “cheerfully to finance the removal of Lord Nelson.”

March 8, 1966

Talk is cheap, but gelignite will get your attention. And that’s what happened on March 8, 1966, when plastic explosives planted by the IRA did their job and blew Lord Nelson and half his Pillar sky high.

Originally, it was thought that Basque separatists had done the job, but Donal Fallon in his wonderful history, "The Pillar: The Life and Afterlife of the Nelson Pillar," believes that it was an IRA job all the way.

The Irish Army, in the very military-sounding Operation Humpty Dumpty, was brought in to remove the Pillar’s stump. Loudly, and with a lot of broken windows on O’Connell Street, they did the job.

It was weeks from the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising and you might expect that Dublin was in shock, but that was not the case. There was a sense of celebration that Nelson had finally gotten his just desserts.

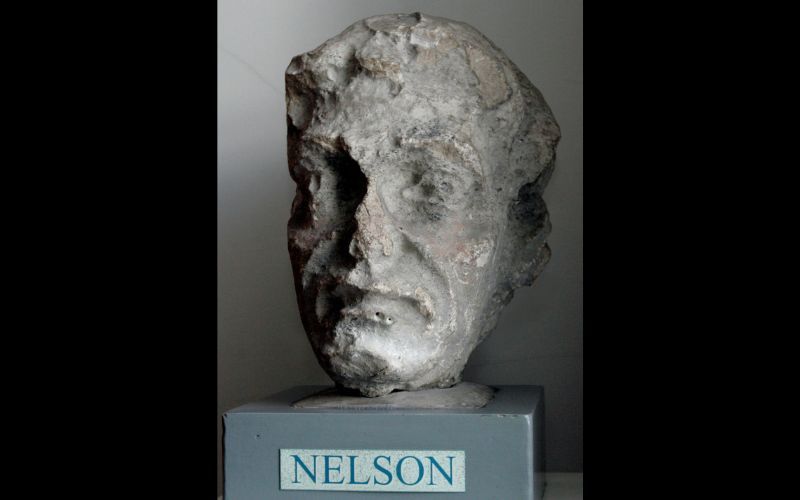

Almost immediately, Lord Nelson’s head became a celebrity. The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, in Dublin to do a concert honoring the Easter Rising, were photographed with it.

Nelson’s head was stored away but quickly stolen by a group of Dublin college students. The Journey of the Head became legend when it was spotted in a London antique shop, made up with lipstick. Eventually, it would find itself on stage with The Dubliners.

Up went Nelson

Of course, the Irish never forfeit a chance to sing a song about any historic event and Lord Nelson's expulsion was no exception. Almost immediately, a group of Belfast schoolteachers known as The Go Lucky Four shot to the top of the music charters with “Up Went Nelson:"

Up went Nelson in old Dublin

Up went Nelson in old Dublin

All along O’Connell Street the stones and rubble flew

As up went Nelson and the pillar too

Lord Nelson

Upon hearing the news, Tommy Makem wrote a scatological tribute called “Lord Nelson” on a New York City subway train:

And then in nineteen sixty-six, on March the seventh day [sic],

A bloody great explosion made Lord Nelson rock and sway!

He crashed, and Dan O’Connell cried, in woeful misery

Now twice as many pigeons will come and shit on me!

Nelson's Farewell

Of course, The Dubliners were not to be outdone and came up with “Nelson’s Farewell." The Dubliners, however, managed to keep it contemporary and made Nelson Ireland’s first astronaut, battling the Russians and the Yanks, and even the French in the Space Race to the Moon. The song is kind of clairvoyant because in three short years, a real Irishman with the evocative Irish name of Michael Collins, would orbit the moon as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to walk on the surface of the moon.

Oh the Russians and the Yanks, with lunar probes they play,

Toora loora loora loora loo!

And I hear the French are trying hard to make up lost headway,

Toora loora loora loora loo!

But now the Irish join the race,

We have an astronaut in space,

Ireland, boys, is now a world power too!

So let’s sing our celebration,

It’s a service to the nation.

So poor old Admiral Nelson, toora loo!

The legend of the pillar remains —and Lord Nelson finds a new Dublin home

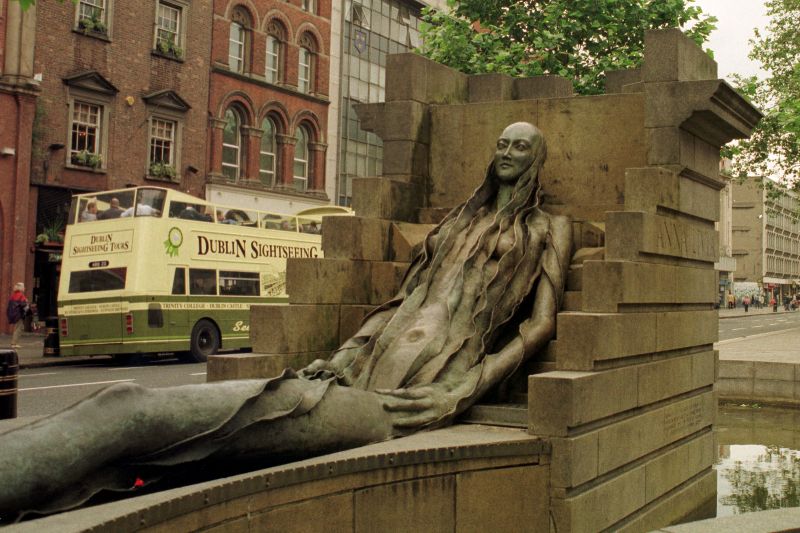

Nelson’s Pillar would be completely removed, but the question became what should Dublin do with the empty space. Another pillar? Another statue? Another something? Finally, a bizarre sculpture called “Anna Livia to Dubliners,” with waters flowing, was put in the space. Of course, she was immediately nicknamed “The Floozy in the Jacuzzi” by randy Dubliners.

The Anna Livia statue in Dublin, 1990. (RollingNews.ie)

Finally, with parts of O’Connell Street becoming tawdry, it was decided to spruce up the area. A competition was held for a replacement for the long-gone Nelson’s Pillar. The result was the “Spire of Dublin” by Ian Ritchie, rising nearly 400 feet high, and costing €4,000,000. It was completed in 2003.

The Spire in Dublin. (Getty Images)

But what of Lord Nelson’s head, you ask? He was never able to escape Dublin for good and you can visit him at the Pearse Street Library, 144 Pearse Street, just a few blocks east of Pearse Station in Westland Row. He sits quietly in the second floor reading room, surrounded by readers pouring over Thom’s Directories, which the library has an exceptional collection of.

At 208 years of age Lord Nelson looks a little stunned. He may have defeated the French and Spanish navies, but in the end, the Irish took him down—literally.

Nelson's head in Pearse Street Library in Dublin in 2010. (RollingNews.ie)

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising" and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," now available in paperback from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected]. You can follow him on his website here.

*Originally posted in 2016. Updated in. August 2025.

Comments