The scale of what is planned is extraordinary. Whether it is all necessary, since the American economy is already on the road to recovery, is another question.

The U.S. added almost a million jobs last month. Unemployment is down to six percent. The growth rate this year is forecast to be at least five percent.

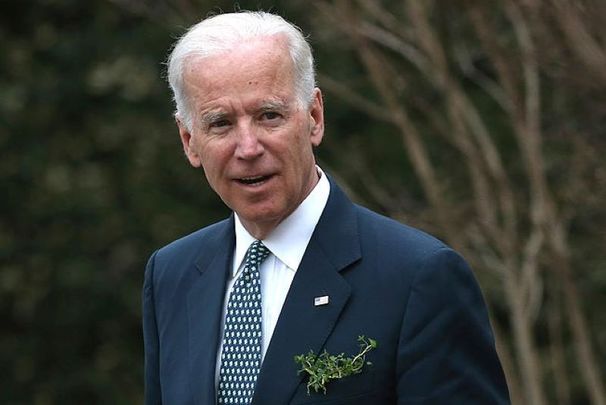

And that's all before the Biden splurge kicks in with its extra trillions. The danger of stoking inflation and wasting vast sums of money is real.

But it's not just the immense scale of the overall Biden plan that is getting attention here. There is a sting in the tail for Ireland, one that has officials here very worried.

This is related to how Biden's plan will be paid for. The nearly $2 trillion in the first half of the plan, which is for Covid relief and was passed by Congress last month, is being borrowed.

The $2 trillion in the second half of the Biden plan, for infrastructure, job creation, and so on, is to be financed to a large degree by increased taxation. There will be income tax increases on higher earners, as well as other measures that will affect individuals.

The most significant change, however, is Biden's proposal to increase corporation tax. Under Trump, this had been cut from a job-destroying 35 percent down to 21 percent. Biden's plan would shift it back up to 28 percent.

Google's European head quarters in Dublin.

Although it may not make the main headlines in the U.S., related to this is Biden's proposal to go after U.S. multinational corporations which avoid tax on the profit they make in other countries by keeping it overseas. Since he intends to whack companies at home with higher taxes, he can hardly let these multinationals off the hook.

So the tax side of Biden's plan includes a global minimum corporate tax rate of 21 percent on American companies overseas. As you know, we have many of them here in Ireland, providing tens of thousands of jobs.

The main reason they are here is our 12.5 percent corporate tax rate. (Not that many of the big players pay the headline rate -- we facilitate them in whittling it down to an effective rate of just a few percent.) Almost certainly they will get credit for whatever tax they pay here, but they will then have to pay the balance up to 21 percent back in the U.S.

The question is, if they are going to be hit with an overall 21 percent tax rate anyway, will they still want to come here? Will those that are well established here already want to expand their operations in the future?

In the good old days – up to recently in fact – U.S. companies with operations in other countries did not pay any tax on their earnings overseas until they brought them home. That led to them holding and reinvesting profits abroad. And a lot of them set up in countries where corporation taxes were low, one of which is Ireland.

Read more

This has meant that our tax regime has been a sore point with U.S. leaders for some time. We deny that we're a tax haven, of course. But our behavior over recent decades tells a different story, allowing big U.S. companies to pay very low tax on their operations here and also helping some of them to avoid tax on much of their global profits by channeling them into or through Ireland.

The first serious attempt to curtail this tax avoidance by U.S. multinationals came from the Trump administration which introduced the 10.5 percent GILTI (global intangible low-taxed income) tax for U.S. multinational companies keeping their profits abroad. You will remember Trump cracking uncomfortable jokes about Ireland's tax setup and in particular complaining about the amount of drugs made in Ireland by U.S. pharma companies for the American market.

So what President Biden is proposing is not new. It's not clear yet how much of an impact the 10.5 percent GILTI tax has had on investment by U.S. companies here.

It does not appear to have been too negative so far, because of a few loopholes. But Biden now wants to double it to 21 percent, and there is general agreement that this level is bound to be damaging for us.

Nor is it just the rate that is a concern. Under Biden's plan, the GILTI tax would be charged on all the profit made, getting rid of the allowance which allows the first 10 percent to avoid the tax.

Also, the tax would be imposed individually in each country the U.S. company operates in, making the shifting around of earnings from subsidiaries in different countries ineffective. Both of these have implications for Ireland.

Facebook European headquarters in Grand Canal Dock, Dublin.

As we said, there is a good deal of concern here about all of this at the moment. No one is panicking so far, because we have yet to see how much gets through Congress and what the final form will be.

The detail will be important for us. But there is an acceptance here that substantial change is on the way.

Biden's determination to effectively tax U.S. multinational companies, outlined in speeches before and during the campaign, made that clear. So also does the level of support on the issue across Congress. All of which would mean that our 12.5 percent corporation tax rate -- and the special tax deals we have been prepared to do to entice the biggest players here -- will no longer be the powerful attraction for U.S. companies it once was.

If the doubling of the GILTI tax does happen we would then have an intriguing decision to make. We could increase our corporation tax rate to retain more of the additional tax that the U.S. multinationals would have to pay. But that would reverse our whole approach to attracting foreign investment up to now and would also be complicated and could have unintended consequences.

Any faint hopes we might have that Biden's love for the old country would somehow shield Ireland from this change are likely to be in vain. We are well known for our very low tax rate and in facilitating profit shifting by multinationals, and this is not acceptable anymore, either to Biden or other senior politicians in the U.S.

Biden said explicitly during the campaign that he wants to target profits in tax havens, and whether we like the definition or not, that includes us.

Like Trump before him, Biden is focused in particular on bringing home the overseas operations of U.S. pharmaceutical companies. Ireland is one of the biggest overseas locations for these pharma giants. The effect here over time could be devastating both in the loss of jobs and huge amounts of corporate tax revenue that fund state spending here.

Read more

Hopefully, we won't embarrass ourselves by playing the Irish card and begging for special treatment. It's not likely to work. Just think of the vaccine shenanigans.

In the wake of Taoiseach Micheal Martin’s St. Patrick's Day virtual visit with Biden, some opposition politicians here were demanding to know why Martin did not plead with him for American vaccines, especially when they learned that some spare vaccines from the U.S. were provided to Mexico and Canada.

That made sense from a U.S. perspective since they are the nearest neighbors and therefore must come first because of the danger of spread across borders. Giving these vaccines to Ireland would not have been justifiable, although that did not stop the moaning here about a missed opportunity.

Trying to get Ireland excluded from Biden's plans on corporate tax for U.S. multinationals overseas would not be justifiable either. And no matter how Irish Biden feels, he won't do it.

Whether we like it or not, change is coming. The drive to get multinationals to pay their fair share of tax has been underway through the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development level for some time.

The aim has been to get all countries, including low tax locations, to agree on a minimum corporate tax level. The figures mentioned up to now have been much lower than the 21 percent in the Biden plan, but this preemptive move by the U.S. may change the game.

This issue is of vital importance to Ireland. Multinational companies are a huge part of our economy and most of them are American.

All the big IT players like Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, PayPal, etc. are here. All the pharma giants, like Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, etc. are also here. Both sectors have continued to thrive during the pandemic. Between them they account for around 80 percent of our global exports and around three-quarters of the corporate tax revenue collected here, as well as thousands and thousands of jobs.

We like to claim that our low tax rate is not the most important reason they are here. We like to say that just as important is the fact that we speak English, provide access to the EU market, have a well-educated young workforce, a stable democracy, and a reliable legal system. We may soon find out just how true this is.

Comments