John Hume, a Nobel Peace Prize winner who helped usher in a era of peace in Northern Ireland, passed away on August 3, 2020 in his native Derry.

One year after his death, his family has shared this reflection on what it was like to have John Hume as their father:

We have been asked many times throughout our lives what it has been like to have John Hume as our father.

In response, our mostly mumbled answers of ‘grand’ or ‘good’ were always somehow lacking, never quite fulfilling the expectations of the person asking. He was just our Da and the fact that he was a politician was just what he did. That he was on TV or that our house was regularly attacked were just part and parcel of life growing up in our family.

To put it in context, other families were facing even more chaotic times, and for many, these were marked by terrible loss. For us, his public profile blended with everyday family life. The thing is that we and our sister and brothers have no point of comparison. We only had one Da and we loved him.

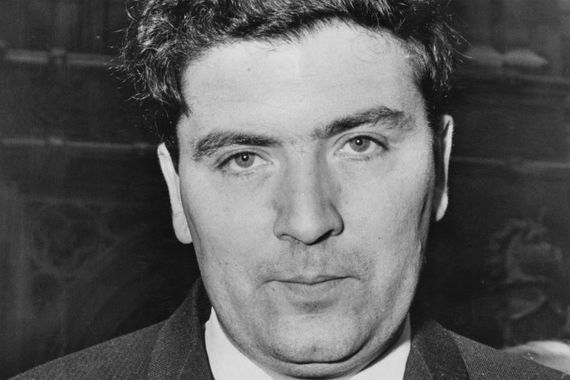

John Hume pictured here in 1969. (Getty Images)

Our childhood was marked by a level of daily chaos which we all took as normal. Until an office was eventually rented in 1979, there was a constant stream of people calling at the house. The phone didn’t stop ringing. At times there could be a TV crew in one room, someone needing advice and support in another, and a list of telephone queries to be answered.

We also learned to recognise and negotiate hostility in the community from a very early age. None of us understand just how our mother coped; Dad was often away and when at home was very often preoccupied. Despite working full time, she managed to respond to demands from all sides and maintain a core of sanity, on which we all leant heavily. Her capacity for warmth and humour amidst all this madness, as well as the support of neighbours and friends, went a long way to keeping us all sane.

Despite being often preoccupied in these years, Dad had a really kind heart, and the stories people have shared with us since his death came as no surprise. He was the least materialistic person we knew and was generous to a fault. We saw him empty his pockets for homeless people on many occasions.

Nothing pleased him more than welcoming people into our home – obviously, the logistics of feeding and providing beds for the same people was left to our Mum! Stories of him giving lifts to hitchhikers across Ireland also resonated in a particular way, given the many people who had given lifts to Dad as his dementia progressed.

Interdependence, and the need to support one another, were unquestionable, foundational beliefs for him. As a child he experienced homelessness and his parents were given a room in a two-bedroomed house by the family who also lived there. Three of their seven children were born there, and when they got their own two-bedroom house, my grandparents gave the front room to Granny’s brother and his wife. These experiences influenced his work with the Credit Union and on the provision of affordable housing.

Gratitude was also foundational. He was deeply grateful for an Education Act which allowed him to access secondary education and was a strong advocate for affordable global access to education.

His studies in French and History began his exposure to different cultures, and over his life he travelled extensively, experiencing warm hospitality in many of the places he visited, often from Irish people who had migrated. He saw the tradition of migration as a defining characteristic of Irishness, and he was always anxious that this be a place of welcome to those who migrate here. Narrow or exclusive definitions of identity and culture were anathema to him and he would be heartened to see the rich diversity of people who have found their home here in recent decades.

Confrontational politics for its own sake depressed and frustrated him, so he could never have stayed in the small confrontational forum of Northern Ireland politics. He saw confrontation as a tool for tackling injustice only.

His politics were formed out of a belief in the power of co-operation and consensus, and the power of collective action to achieve positive change for the many, so the collaborative relationships within the larger frame of the EU liberated much potential for him. Brexit would devastate him, but if he were alive and active, he’d be thinking up creative ways to re-form those bonds with Europe and reawaken a wider political consciousness.

Dad didn’t seem to be daunted by what seemed impossible. He had incredible self-belief, and his confidence in his capacity to persuade others never diminished, even when he was frail, blind, and limited by dementia.

John Hume pictured here in 2010. (RollingNews.ie)

His health was under strain for a long time and he didn’t have a great capacity for self-care; one of the sad things about men of his generation. While to begin with, his poor memory caused him daily anxiety, in later years he became much more content, in no small amount due to the consistent, patient, and loving care of our mother. Even when he had lost his sight and was living in a Nursing Home, every second sentence began with “Pat”.

It was a huge comfort to us that he kept his indomitable personality until the very end, asking endless questions of his young carers about their families and inviting them to come and stay at his house in Donegal. Truly indebted to the team of nurses and carers in Owen Mór, who have worked incessantly with little material reward through the Covid pandemic, we strongly believe, as he would, that the work of care in society needs to be valued much more highly.

Our dad lived a very public life but was always fully and unapologetically (sometimes to our intense mortification) himself. In today’s image and social media dominated politics he wouldn’t have a chance. He was full of paradox. Forgetful about practicalities but never about principles. He lived at an intense pace but gave the same message over and over.

Deeply connected to his home place, he was an instinctive internationalist who rejected narrow definitions of identity. He could be very fearful about small worries but faced the most daunting risks on an almost daily basis. He often seemed emotionally absent but with the wisdom of hindsight we understand how deeply emotionally engaged he was, with the bigger issues.

The overwhelming response we’d have now to the question of what it was like to have John Hume as our father would be one of enormous gratitude. Grateful for his being the unapologetic, grounded, lofty, demanding, generous, compassionate, gregarious, deeply serious personality that he was. Grateful for the community which sustained us all through the tumult of our childhood and grateful for the open-hearted attitude to life which we hope we have inherited.

Ni bheidh a leitheid arís ann.

Comments