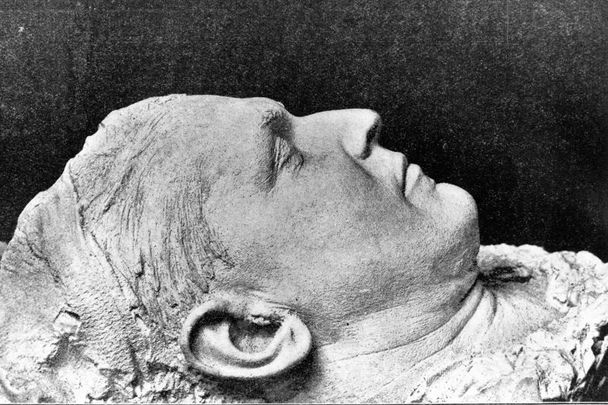

MacDara Ó Conaola recounts the story passed down through his family about the night that his grand-uncle's father Albert Power RHA made Michael Collins' death mask in Dublin.

My grand-uncle John and I were great pals. We had time for each other and had similar interests and views on life.

Within the family, we called him John, but his ''real'' name was James, James Power, which, for continuity purposes, is how I will refer to him from now on.

James Power (1918-2009) was a renowned sculptor and painter from Berkeley Road in Dublin. He attended the National College of Art in his teens where he studied sculpture under Oliver Sheppard and painting under Seán Keating. He had, however, learned almost everything already from his father, the master sculptor Albert Power RHA (1881-1945).

"When he was a boy, he'd be always at Daddy's feet in the studio. Watching everything. And Daddy would give him modeling clay and show him how to carve faces and shapes," my Aunt Josie (Josephine Power 1915-2005) would tell me of her younger brother.

He was very inquisitive and wanted to know how things worked, or how people lived in different parts of the world. He would often ask me about life on The Aran Islands. In fact, I remember at my grandmother Agnes Power's (James's older sister) wake when James arrived at the house the first thing he asked was, "are The Aran Islanders here?" To which my uncle-in-law answered, "The Aran Islanders are always here!"

James molded a bust of the legendary island seanchaí, Joe Mháirtín Ó Flaithearta (1881-1965), who himself had regaled generations of island-folk with mythical fables and fairy-tales.

James’s other notable works included the busts of former President Erskine Childers, US President John F. Kennedy, writer Máirtín Ó Cadhain, author of The Irish National Anthem Peadar Kearney, as well as the Matt Talbot statue at Talbot Memorial Bridge in Dublin, The 1916 Memorial on Sarsfield Bridge in Limerick, and the statue of Fr. Eoghan Ó Gramhnaigh in Athboy, Co Meath.

He was also skilled in taking death masks, a craft that was very common in previous decades and centuries before the advent of film and photography. He took his own father’s death mask in 1945, and in 1964, the death mask of his fellow North Inner City Dubliner, Brendan Behan.

I recall at the aforementioned wake, James took my grandmother’s death mask. While taking the death mask, applying the plaster to the oiled face, waiting for it to set, and then removing it, James recounted the time he took Brendan Behan’s death mask. It was in the Meath Hospital and James sneaked into the candle-lit room and proceeded to mix the plaster and apply it to Behan’s oiled face. When it was time to remove the plaster, which demanded a bit of gentle force, James placed his elbow on Behan’s stomach for leverage while removing the cast from his face with his other hand. With the force of James’s elbow on Behan’s stomach, however, the sound “buck” came from his mouth, which startled James who lifted his elbow quickly which in turn created the sound “off”, so what he heard from Behan was, "Buck off!"

Incidentally, a priest, whose name escapes me now, who was present spoke to James and told him, “I remember seeing your father doing exactly what you’re doing there ... with Michael Collins.’’

He had been present 42 years earlier in St. Vincent’s Hospital, Dublin, where Albert Power, James’s father, took the death mask of Michael Collins.

James and Auntie Josie would often tell me the story of that night. They were aged four and seven respectively but remembered vividly the banging on the door in the middle of the night and their father being hurried into a Crossley lorry by uniformed men (there were snipers all over Dublin during that period, so the less time exposed the better), and then their father telling them later, and for many years after, what had happened.

Albert Power, best known for his Pádraic Ó Conaire statue on Eyre Square in Galway, was the leading sculptor in Ireland in the '20s, '30s, and '40s. In the years before and after the Civil War, he worked on pieces of figures from both sides of the conflict. Just earlier in the summer of 1922, in July, he had taken the death mask of Cathal Brugha from the anti-treaty side.

His friend, physician Oliver St. John Gogarty, was at St. Vincent’s Hospital when he arrived there and was with him while he took the death mask of Collins. Power, having studied human anatomy as artists such as Leonardo da Vinci had for centuries before him, appreciated Collins’s “fine ears” and decided to include them in their entirety in the death mask, which was not the usual practice.

When it was time to remove the hardened plaster, Power noticed blood and other matter on his hands and that the back of Collins’s head was split, and that the bandage was to keep the skull intact.

After much maneuvering, Power managed to remove the cast. He remarked to Gogarty that that must have been where he was hit. Gogarty said that it was the exit wound and pointed to a small hole behind Collins' right ear and said that that was where the bullet from the Mauser pistol entered his skull and that the singed hair indicated that he was shot at close quarters.

The most commonly-believed theory surrounding Collins' death is that he was shot by an anti-treaty sniper, although this has never been corroborated and conspiracies about Collins' death have been rife.

James would always “show’’ me how his father tried to pull the cast off Collins’ head by grabbing the back of my head gently but firmly with his strong hands, demonstrating how difficult it was to remove the plaster cast. I suppose he wanted me to experience and remember the feeling. Let me just say I can still feel it and see the image of Collins’ head in my mind.

"We were explicitly told not to say anything at school or to anybody about what he told us. You’d be likely to be bumped off yourself," James told me about having this knowledge during those years.

It was a similar situation in the case of Arthur Griffith who had died just ten days earlier. Present again were Albert Power and Oliver St. John Gogarty. Power took Griffith's death mask. Gogarty, James’s father told him, had mentioned that the condition of Griffith’s skin was consistent with poisoning.

And again, the family was told not to say anything to anybody about what they had heard. Different times I suppose, and a lot of pressure on kids you would imagine to have this information in their heads, but it seems they were able to keep it together.

James, or Uncle John, was a great man, a great artist, and a great friend. I am privileged to have known him. I miss him and hope he is in good company in some other realm, sharing space with the likes of da Vinci, Joe Mháirtín, Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, and Niamh Chinn Óir.

*MacDara Ó Conaola is the co-founder of Gaelic Green Tongue, an organization aiming to help and support endangered languages around the world, including Irish.

Read more

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments