The enslavement of black people provides a poignant narrative central to understanding the story of America, and there are two versions of that story competing for emphasis in the media and in the curriculum in the country’s schools.

One stream is aptly represented by The New York Times’ 1619 Project, a major research effort published to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first slaves from Africa. Somewhere between 20 and 30 captives from that faraway continent docked in a coastal port near Point Comfort in Virginia on an August morning 402 years ago.

Selling these dark-skinned people into slavery left them with no rights, completely at the mercy of their purchasers. Families had no standing. The children, barred from schooling, were bought and sold at the whim of their owners. There were no white slaves in America, so this represented the establishment of race as an indelible feature of America’s core identity.

By comparison, the masses of Irish emigrants who made their way to the New World during and after the Great Famine in the second half of the 19th century were treated abysmally. They suffered pervasive discrimination including subjection to crude stereotypes highlighting their alleged inferiority.

The powerful Know Nothing movement lumped them – black, Irish, and Catholic – together as incapable and unworthy of full participation in American life. Still, the Irish never carried the mark of slavery, and most considered their white skin a bonus as succeeding generations made their way to respectability.

The second narrative starts in 1776. The vaulting language of the Declaration of Independence, rejecting British colonialism with all its pomp and pretensions, still resonates: “All men are created equal” with “unalienable Rights” to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Yet this inspiring rhetoric came from the pen of Thomas Jefferson, a man who over his lifetime owned over 600 slaves. His noble message was relayed to the 13 fractious colonies, all of whom subscribed to some version of race-based slavery. Five of the first seven American presidents – Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and Jackson – owned slaves.

Then the colonies became states and they agreed to a new Constitution. It is a revered document in many American homes, but that first version codified slavery, explicitly approving a slave owner’s right to capture fugitives who crossed state lines trying to escape their forced servitude. And in apportioning members to the House of Representatives, blacks were counted as having the value of three-fifths of a white person.

Racism can be appropriately seen as a social disorder and a moral calamity. Ninety years after the British departed a savage Civil War was fought, largely because the slave system had become so morally repugnant that many of the rulers and thinkers of that time, abetted by some religious leaders, were determined to end it. The Union side, led by Abraham Lincoln, defeated the Confederate states, and all slaves were granted freedom after the Union victory.

Unlike other wars where the losers are humiliated and their philosophy discarded, the defeated side in America’s Civil War got to tell nostalgic stories about their contented lifestyle in a slave-owning society. Some books and movies portrayed the past times of white supremacy as the good old days.

Monuments were erected up and down the Southern states and beyond to Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and other prominent rebels as if their blatant treason amounted to some version of patriotism.

Blacks could vote after the Union victory in the Civil War but, following a brief, hopeful Reconstruction period, Jim Crow laws and practices took over. These were so repulsive and cruel that millions of African Americans abandoned their homes during what is called the Great Migration and fled north to the big cities where, although prejudice was still a salient factor, they had a better chance of finding a job and some sense of dignity.

Religion was a strong force in those years. Powerful Protestant communities and growing Catholic numbers did not rally in opposition to the repugnant belief that God created two classes of unequal human beings, which was a core perspective not only of the slaveholding society but of the Jim Crow culture which followed it and lasted until President Johnson’s reforms in the 1960s.

The main message of the current Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement asserts the equality of black people at a time when the economic and penal systems often fudge that principle. Opponents mock BLM by proclaiming unfairly that blacks are looking for special privileges.

The post-Civil War debates about the various entanglements of white supremacy continue, especially as many state legislatures with Republican majorities pass laws to limit the voting rights of black and brown people. The Jim Crow mentality no longer applauds the gallows, but all kinds of lame excuses are offered for restricting the voting rights of non-white citizens.

George Floyd’s murder led to massive demonstrations calling for changes in policing in all American cities. These gatherings, mostly young people of all colors, motivated many first-time voters to cast ballots in last November’s presidential race.

Make America Great Again has evolved into Teach America’s Great Again. Steve Bannon, the propaganda guru of the far-right, was clear about his vision of the big battle ahead: “The path to save the nation is very simple – it is going to go through the school boards.”

Last fall, the American Historical Association and Fairleigh Dickinson University conducted a major national survey to learn what Americans think about historical studies. The results showed that 70 percent of Democrats believe that any study of the past should question the integrity of institutions and leaders from previous times. However, 84 percent of Republican respondents felt that the goal should be to celebrate the past, especially the leaders in the American Revolution.

Most conservatives look askance at any focus, especially in the classroom, on the awful story of slavery. They don’t want to hear about 1619, and they believe that the undoubted heroics of Washington and Jefferson should be at the center of the curriculum in every school.

Yet there have been dramatic positive changes in race relations, culminating in the election of Barack Obama over white Republican candidates in 2008 and 2012. A majority of the white electorate voted for his Republican opponent, but Obama could not have won without strong support from Americans who don’t look like him. From a historical perspective, these victories represented real progress and had monumental symbolic significance.

There is now a solid black middle and professional class. While disproportionate rates of poverty persist and serious wealth disparities remain, nearly half of African-American families have annual incomes over $50,000.

Black women are graduating from college at really encouraging rates, and teenage pregnancy numbers in minority communities have plummeted.

Derek Chauvin’s conviction for the murder of George Floyd, after an extended televised court trial, sent a clear message that the law must be administered fairly. Demands for structural changes in policing are harder to reject and, indeed, are already leading to positive movements in many cities.

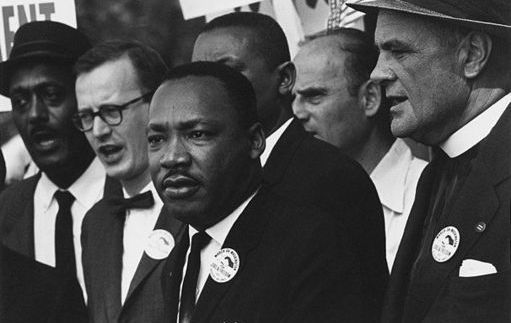

Martin Luther King famously dreamt of a society where people are judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. The continuing cross-community vibrancy of the BLM movement suggests that we are moving in the right direction.

*This column first appeared in the September 15 edition of the weekly Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral.

Comments