In this two-part report, leading up to the big FDNY vs. NYPD GAA match being played in Rockland on September 18, the Irish Voice, sister publication to IrishCentral, talked with several former and current members of the FDNY and NYPD Gaelic teams to talk about their 9/11 experience and representing their departments on the football pitch.

“I might not think about it every day,” says FDNY Captain Denis McCool. “But it’s something that that comes up regularly – maybe once or twice a week. Something will happen, usually something funny or something that will jog my memory about somebody I was close with. I might not think directly about 9/11, but it’ll remind me of some of my closest friends who didn’t make it out.”

“So, what do you want to know?” Eddie Boles, now an FDNY chief with the 17th Battalion, sits down at the end of a beautiful, long table inside the quarters of Engine 92 and Tower Ladder 44 on Morris Avenue in the Bronx. The table is a special design – a shiny coat glides over a Maltese cross with the house’s companies inscribed into the wood.

“I wasn’t working on 9/11,” Boles begins. “But I was in the firehouse – Ladder 34 in Washington Heights. It was primary day in New York City and the union had organized a bunch of us to do some political action work for the mayoral race. I got back into the firehouse after going for a run. It was such a beautiful clear day I just kept going and decided to run across the George Washington Bridge.

“I could clearly see into lower Manhattan that early in the morning – the view was just crystal clear, no haze, not a cloud in the sky, beautiful. I got back to the firehouse and when I came back downstairs to the kitchen after a shower, the TV was on and you could see the smoke coming from the first tower.”

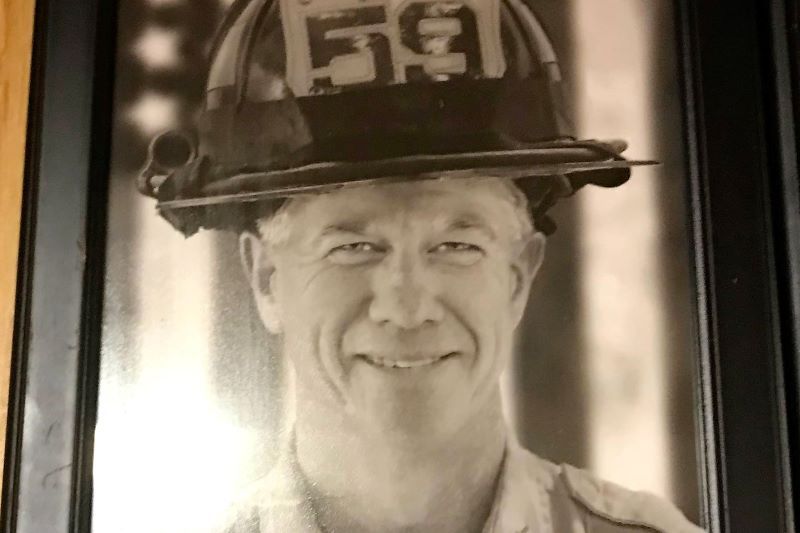

Captain Eddie Boles. (Irish Voice)

Detective Patrick Donohue was a police officer within the NYPD’s Transit Bureau.

“The NYPD was getting ready to send a task force to Washington, D.C. for the World Economic Forum that was going to take place a few weeks later. I was in a classroom training on how we were going to prepare to go to be in D.C.”

Paddy, as he is commonly known, has gone on to be a regular with RTÉ Radio for New York inter-county matches alongside Marty Morrissey. “I remember hearing another officer’s radio squawking about a small plane that had hit the Trade Center. Shortly thereafter there was a buzz in the building that was noticeable from our classroom.”

“I was off that day,” Firefighter Sean Fitzpatrick says. “I was up at my father’s place with my son doing some work around the house. I remember coming into the living room and the TV was on. The first tower had already been hit and the news kept saying a small aircraft. Then we were watching as the second plane hit and I just remember thinking that’s no small plane.”

Captain McCool who was then a Lieutenant with Engine 92 in the Bronx had departed with other firefighters from the Bronx for a golf trip in the Poconos.

“I was in one of the first groups to tee of that morning, so I was already on the eighth green when a guy from Ladder 44 came running up to the green saying, ‘They just hit the towers again.’ The guy who was yelling this at us was a notorious chop buster so for some reason I thought he was joking.

“But when I finally looked up and saw his face, I knew he was being deadly serious. He had honestly looked like he seen a ghost.”

“I remember waking up and turning on the Today show,” Captain Bill Horan, then a firefighter with Engine 62, says on his way home from his shift on Staten Island.

“Toward the end of the broadcast, they cut to local news with the image of the first tower and smoke blowing out the top of it. You could already see the hole in the side of the building. I started to think about heading to the firehouse, but I wasn’t sure if they were recalling guys in yet.

“I left the room with the TV for a second and I could hear the hosts of the show shouting and gasping. I returned to the room to see a massive fireball coming from the second tower. I knew then I had to go.”

On the morning of September 11, 2001, NYPD Detective James Huvane was a member of Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s security detail. He had started his morning by heading to the Peninsula Hotel to advance a trip the mayor would take there later that day.

“I was walking along with Patty Barone who was the primary bodyguard for the mayor and she got a call on her cell phone saying that a small plane had hit the building. I remember her face was extremely serious.”

Huvane decided to jump in his car and head downtown. “I figured it was still early enough in the morning that the East Side would be clear enough and I jumped on the FDR. I decided to get off before the underpass at the bottom of Manhattan and drive through the city streets to the Trade Center. I just remember seeing a few people walking on the street. Then more. And then more. Until it was actually too dangerous for me to keep driving without running anybody over.”

Huvane then decided to carry on the rest of the way on foot. “I remember walking into this wall of people who were walking the other way. I just kept thinking, ‘How bad is this that I’m the only one going in this one direction?’”

The Twin Towers in New York City on September 11, 2001. (Getty Images)

Captain McCool, with several others, rounded up the other members of the FDNY who were out on the golf course. “I remember we tried to get a hold of Pennsylvania State Police to either get an escort or to warn them that we would be driving fast back to New York. We never got through and it only dawned on me afterward that they were probably busy with the plane crash in Shanksville. We decided to go and if we got pulled over it was what it was, we would just have to explain ourselves.”

McCool and the group of firefighters in the convoy began to call ahead to see which routes back into New York City would be best.

“As we got further along, each Hudson River crossing closed – the Holland Tunnel, the Lincoln Tunnel, and we had originally heard that the George Washington Bridge was opened, but it was imminent when the Port Authority was going to decide to close that as well. We ended up having to go all the way up to Rockland County and jumping on the Tappan Zee Bridge. Then we had to come back down through Westchester, the Bronx, and into Manhattan.”

Huvane made his way across the base of the World Trade Center trying to get a grasp on the situation. “It became treacherous. I was walking along and I could hear these loud bangs. I looked up and could see people falling from the building with their arms out and then hitting the ground,” he recalled.

“I tried to reach Patty Barone on the radio to find out where we could bring the mayor. She had decided to move him to a location north of the Trade Center to what ended up being a Merrill Lynch satellite office of some sort. I meet Patty there and the mayor is inside trying to get a hold of the White House.

“At that point, the mayor turns to me and asks if his kids are all right. Told him I would go and find out. I went back outside and right in front of me are shoes and an engine. The engine of a plane.

“As I was trying to make sense of what I was seeing, a large crowd of people begin to run toward me and as I try to comprehend what they’re running from, a large plume of smoke begins to come at me.

“I turn and run as fast as my fat Irish ass can. I’m like Indiana Jones when the boulder is chasing him, that’s what it felt like – I wasn’t gonna be able to outrun this thing. I didn’t know what it was, but I knew it wasn’t good.”

Chief Boles sits only slightly relaxed in the old wooden chair at Engine 92, Ladder 44. His Irish blue eyes pierce out past crow’s feet that fight to show on his face. Every once and a while he looks up at the television to his right to check in on the Yankees.

“We got onto city buses that we commandeered. After we grabbed cases of water, we flew down the West Side Highway. Both towers were already down. As we got to the base of wreckage, I had a flashback to old footage from the Vietnam War – of the refugees leaving villages by the hundreds. That’s what lower Manhattan looked like that day.”

“I was terrified,” Detective Donohue says. “We had piled onto NYPD buses and headed down the FDR Drive. While we were in transit, the first tower collapsed. By the time we had stopped and gotten out at a command post set up on South Street at a Pathmark there, they were talking about additional buildings coming down.

“I was absolutely terrified…everybody on that bus was. Guys were phoning or trying to phone home to family members to tell them they were okay. I left a voice message on my sister’s answering machine saying to get word to my father who was in Ireland at the time that I was ok, but I was going downtown, that I didn’t know what was going to happen, and that I would try and phone again when I got a chance.”

Firefighter Fitzpatrick, like so many other first responders, had piled onto city buses with 30-40 guys headed for the lower tip on Manhattan.

“We saw the bus in front of us stop and those group of guys got off and started to run. So we stopped our bus and got out to start running after them. At one point, we made a left and the group in front of us was at a dead stop. It was so fast that we basically ran into the back of them. Guys were like, ‘Why the hell did you stop?’ Then we all looked up and saw this mountain of debris. It was like two to three stories high. We thought at this spot there couldn’t be too many people alive. It wasn’t until we climbed up the debris that we saw how massive this area was.”

In a spare FDNY rig Bill Horan’s officer was able to grab, he and other members of Engine 62, Ladder 32 go onto the West Side Highway heading for the World Trade Center.

“The way I was facing in the jump seat in the back of the cab, I stared out at the Hudson River. It was just a gorgeous, gorgeous late summer’s day,” he says in the hushed tones of a man who doesn’t want to give away a secret.

“I just kept thinking how is it so perfect over here and straight ahead, like what the hell am I walking into?”

When Denis McCool and his group arrived at what was quickly becoming known as Ground Zero, they immediately began to search sections of the pile.

“I had gotten a couple of glimpses of the site from my seat on the bus going down the West Side Highway. But being there, there was just no way I could’ve ever imagined that. The twisted steel, the fire coming out from beneath it… I don’t know what hell looks like, but after that initial look, I have a pretty good idea.”

As a lieutenant, McCool was dispatched to lead a team of five or six firefighters to do searches on the pile.

“We were crawling down into these voids and the steel is still shifting, but I did really believe we were going to find guys. That fighting spirit, survivor instincts of firemen…I really believed that guys were huddled somewhere in a stairwell beneath the steel somewhere below where we were standing and it was only a matter of time before we would hear from them or find them.”

Having made his way around the pile from the north side down to the south and then back up around on the east side of the pile, Bill Horan had surveyed the debris field from the perimeter.

“It reminded me of a show I had been watching not that long before 9/11, about what a nuclear winter looked like. I remember walking up to the pile from a side street walking from east to west and everything was grey. Dust and papers were blowing everywhere. I just felt like it was snowing.”

Paddy Donohue had made his way to the pile the night of September 11.

“I remember there was a real positive buzz around the site that night. A woman had called into 911 saying her sister was in the rubble and was trapped and was communicating by cell phone. At the same time, engineers had set up lasers to tell when buildings surrounding the site were shifting and in danger of collapsing.

“So we’re on the pile that night and the engineers and the NYPD Emergency Services Unit is trying to figure out a way to find this woman. Suddenly the lasers started to detect movement. I remember the horn off a fire truck blasting three times to signal an immediate evacuation. So we all dropped what was in our hands and we all ran. We were hopeful for those first three days that we would find people alive somewhere down there. But it never really happened after those first few hours.”

Later in the evening of September 11, Horan had made his way out of the pile and started to move a little north.

“I remember going into the borough of Manhattan Community College just north of the site. I was trying to find a phone to call my wife and tell her I was okay. There was a fireman on the phone next to me and he was, just, he was just uncontrollably sobbing. He’s telling whoever is on the other end of that phone call, ‘They’re all dead. They’re all gone. All the firemen are dead.’”

September 11, 2001: Firefighter Gerard McGibbon, of Engine 283 in Brownsville, Brooklyn, prays after the World Trade Center buildings collapsed. (Getty Images)

Today, the only hint of 9/11 at what was once known as Ground Zero, is through closed eyes. Squeezed tight to enhance the smell, the sounds, and the sight of it all.

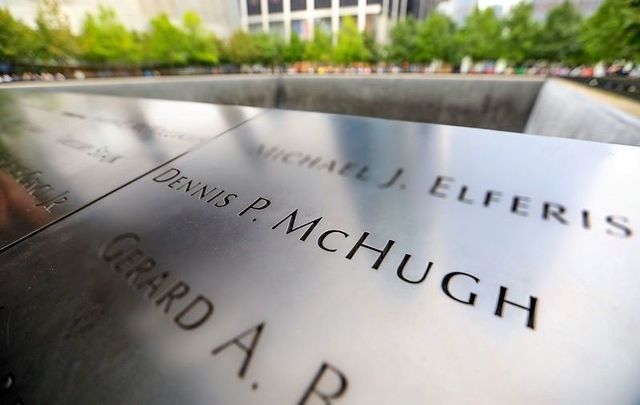

Two pools sit in the footprints of the great Twin Towers as if a dinosaur had roamed through this site on its way to extinction. Names inscribed onto metal cladding surround the constantly draining pool.

Too many to count. Too many… period. 9/11 cannot be remembered alone here.

September 11 is etched into the faces of those who lived here, who worked here, who responded here. It goes beyond the expensively engineered architecture or well-thought-out memorials.

It is branded into the soul of this city. Into the fabric of these lives who were fortunate to remain on this planet.

Dennis McHugh, a member of the FDNY’s GAA team perished along with members of his unit, Ladder 13.

“I remember going to Dennis’ funeral in Piermont, New York. I was there with obviously a bunch of other FDNY members. I had played Gaelic with Dennis and his brother Tommy who is also a firefighter in the Bronx. We played for Rockland and it’s actually Tommy that got me to join Rockland.

“I remember walking in the door of the church and meeting two other Rockland GAA men – Mick Healy and Paul Rowley, and I felt this overwhelming sense of community and pride of the GAA and instead of sitting with other firefighters, I sat at the back of the church with Mick and Paul. And we balled our eyes out. We cried like babies the entire funeral – and I didn’t do that at any other funeral.

“It was just so heartbreaking. Great, great guy – you can’t say enough of how great a guy Dennis was, just an absolute gentleman with such a young family, I just couldn’t get past the fact he was never coming back.”

*This column first appeared in the September 8 edition of the weekly Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral.

One World Trade Center in downtown Manhattan. (Getty Images)

Comments