In early 1864, the start of the fourth year of America’s brutal Civil War, with the prospects of a Confederate victory rapidly slipping away, Cork-born Confederate General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne had a clear vision of the battles that lay ahead and what was needed to win them.

Cleburne’s proposal: Let the South's 1.4 million slaves fight for emancipation. He saw tens of thousands of urgently needed Black troops flocking to fight under the Confederate battle flag.

Cleburne's notion was revolutionary and explosive and could have produced one of the greatest ironies to emerge from the four-year struggle to vouchsafe the Confederate States of America. The proposal, formally tendered to his commander in January 1864, would replenish the thinning ranks of the badly outnumbered Confederate army and would have led to slavery ending to save a nation founded to preserve slavery.

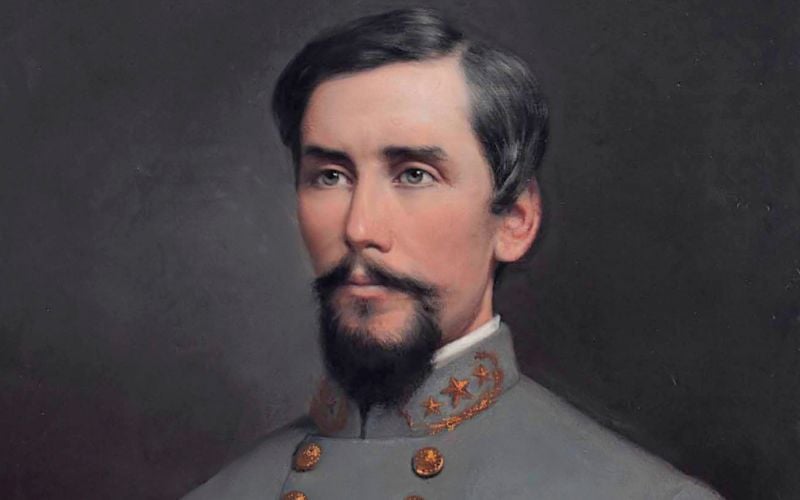

Major General Patrick Cleburne by Louis Guillaume.

A look at the 1860 census reveals one of the reasons Cleburne would make this radical (to slave-owners) proposal. The population of the North in 1860 - excluding the border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri - was approximately 18.5 million. The population of the 11 soon-to-be Confederate states was about 9 million.

This manpower deficit of 2 to 1 would seem a formidable obstacle, but the actual ratio was worse than that. Some 40 percent of the South's population, about 3.5 million individuals, were slaves. Without tapping into that potential source of soldiers, the South actually faced a 3-to-1 disadvantage in manpower. A reasonable person might conclude, as Cleburne must have, that 3 to 1 was nearly impossible to overcome, but 2 to 1 might not be.

Would the slaves have fought for their former masters? Cleburne was optimistic and, flashing his Irish heritage, waxed poetic about the prospect of slaves fighting for their masters in his proposal: "Will the slaves fight? The helots of Sparta stood their masters' good stead in battle. In the great fight of Lepanto, where the Christians checked forever the spread of Mohammedanism over Europe, the galley slaves of portions of the fleet were promised freedom and called on to fight at a critical moment of the battle. They fought well, and civilization owes much to those brave galley slaves."

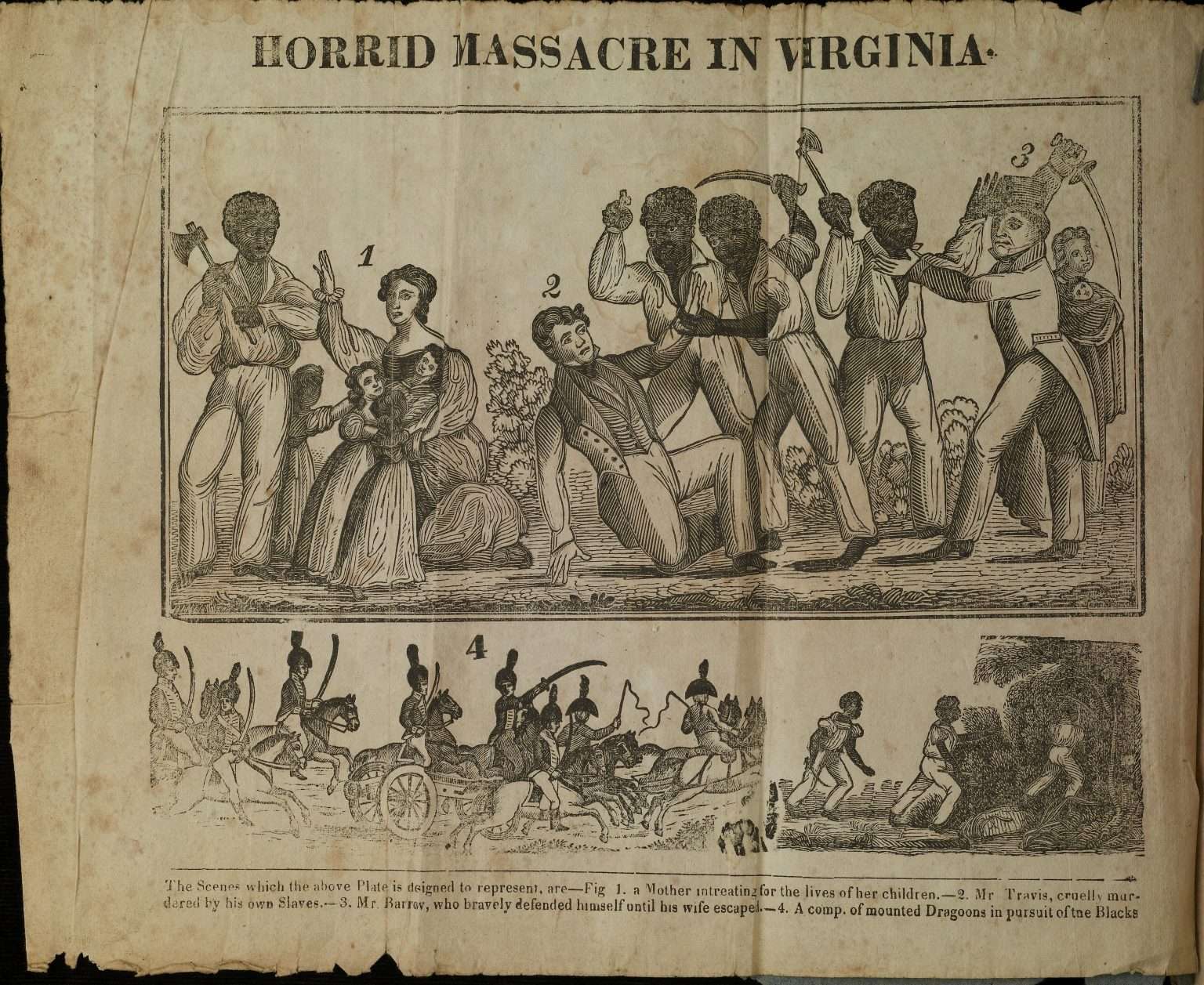

Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in 1831.

Cleburne's eloquence on the subject notwithstanding, the question became moot. Confederate leaders saw the scheme as incendiary. The specter of armed Blacks terrified the South, evoking memories of Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in 1831 (pictured above). In fact, these same leaders earlier deemed that black Federal soldiers were not to be taken alive. The fathers of the Confederacy, which embraced George Washington on its currency, recoiled from the notion.

Of all the off-the-field actions taken by officers in the American Civil War, Cleburne's proposal for emancipating Southern slaves in return for military service stands out as one that could have been the most consequential.

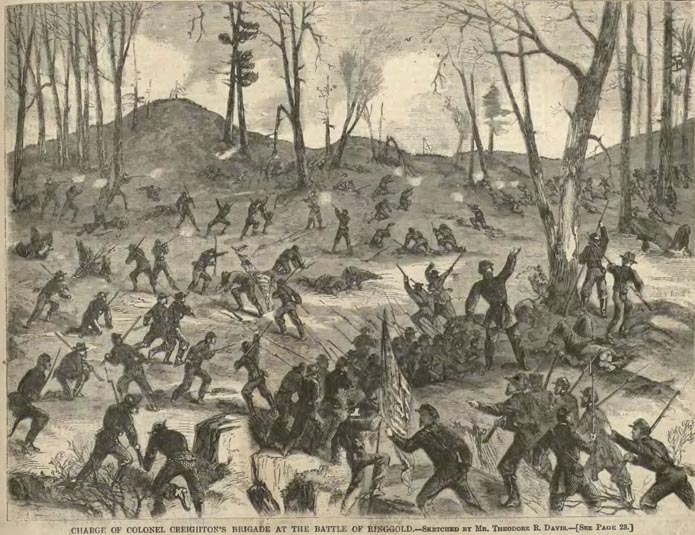

At the moment that Cleburne, a major general, put forth this proposal, he was at the zenith of his career after his stunning victory at Ringgold, Georgia. It was a victory that he won in independent command. There was no position in the Confederate Army that he might not have reasonably aspired to then.

A contemporary drawing of the Battle of Ringgold Gap.

When Cleburne first showed his notes on this proposal to staff officer Irving Buck, Buck told him it would raise a "storm of indignation against him." He also cautioned him that there was at that moment a corps in the Army of the Tennessee (the primary western Confederate army) with no lieutenant general to command it and that he would certainly be a leading candidate for the post, given that the Confederate Congress had just voted him the thanks of the nation for Ringgold. Buck told Cleburne he was certain that this proposal would destroy his chances for promotion.

Cleburne must have been aware of that already, but Buck laid it before him in no uncertain terms. Cleburne would not be deterred. He told Buck he felt it was his duty to bring forth the proposal, no matter what the personal cost.

Was the Civil War fought over the issue of slavery or states' rights? This question has been debated long and hard ever since that tragic war. Cleburne's proposal, it would seem, strikes directly to the heart of that argument. Surely, his proposal proves that Cleburne believed the war was being fought to save slavery because he was willing to end slavery to save this new country that he had already shed blood for, his and that of hundreds of men under him.

The reaction of most of Cleburne's fellow Confederate generals, and especially the reaction of the Confederate government, tells a different story. They did believe it was about preserving slavery. Gen. Joe Johnston, commander of the Army of Tennessee, decided it was a bad idea even to let the government know that it had been proposed.

Gen. William Walker — who was incensed by the proposal — bypassed Johnston and sent a copy directly to President Davis. Davis’s reaction was swift and unambiguous. He sent a message to Johnston immediately stating, in part, "Deeming it to be injurious to the public service that such a subject should be mooted, or even known to be entertained by persons possessed of the confidence and respect of the people ..." he instructed Johnston to hush up the entire incident.

Johnston's judgment proved correct, for it probably cost Cleburne any prospects for further advancement, arguably dooming him to his eventual death at the command of a division at the Battle of Franklin on November 30, 1864.

Cleburne's final moments at Franklin, by Don Troiani used with permission of artist.

Later in the year, when the circumstances of the Confederacy had worsened considerably, a bill very close to Cleburne's proposal was introduced in the Confederate Congress. Even then, with the demise of their cause staring them in the face, many Confederate politicians were bitterly opposed to the idea.

A representative from Mississippi said, "All nature cries out against it. The Negro was ordained to slavery by the Almighty. Emancipation would be the destruction of our social and political system. God forbid that this Trojan Horse should be introduced among us." So many did not share Cleburne's view that saving their new nation was more important than saving slavery.

The bill allowing Blacks to enlist in the Confederate army would ultimately pass on March 13, 1865, far too late for it to matter. And the law did not even expressly state that enlisted slaves would be freed. It stated, “that nothing in this act shall be construed to authorize a change in the relation which the said slaves shall bear toward their owners.” What incentive they thought this would give any slave to enlist is hard to fathom. Some in the Confederate Congress, it would seem, could not bring themselves to place "slave" and "free" in the same sentence, even as the walls closed in on them.

In the end, Cleburne's judgment was vindicated. We are all left to wonder how history might have been changed if, in January 1864, Jeff Davis and the rest of the politicians of the Confederacy had possessed his foresight, as well as his courage to act on it. JG

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments