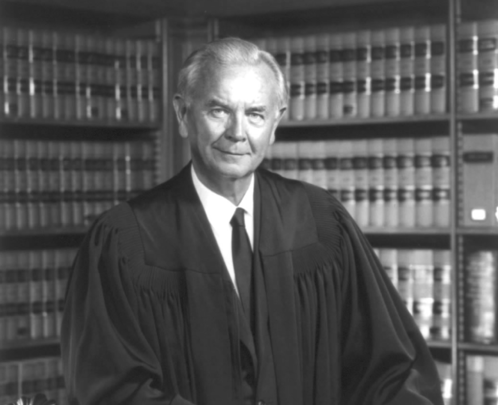

As we approach LaborDay, we would be well served to consider the words of a famed Irish American jurist who practiced in the field of labor law before joining the bench, the late Supreme Court Justice William Brennan.

He was the son of Irish immigrants from Co. Roscommon. His father worked his way up through manual jobs to become a leader of organized labor in New Jersey. Justice Brennan himself, after graduating from Wharton and Harvard Law, handled labor disputes at a private firm and then served in the Army in World War II, where he served for a time as chief of the Labor Branch.

Scholarly reviews of his subsequent labor law opinions from his Supreme Court tenure note a predisposition for ensuring that labor and management hard robust economic tools at the irrespective disposals — and that the protection for individual workers would be best assured through strong unions and compliance with mandatory processes.

But as we close out this summer, other words from this famed Irish American sound clarion call about a different form of protections for individuals — in this case, about fundamental rights. There has been much debate the last two months about the variation of “originalism” used by the Supreme Court in its recent decisions on fundamental rights. Originalism interprets the

Constitution according to what today’s justices believe to be its original meaning, through their current perception of what the then-public would have thought to be a given provision’s meaning at the time it was ratified. The recent decisions employ a uniquely strict version of originalism that would limit fundamental rights to those “rooted” in the “history and tradition” of the “nation.”

Justice Brennan did not adhere to this restrictive view. He said nearly 40 years ago that “we current justices read the Constitution in the only way that we can: as 20th century Americans."

There is a particularly glaring omission today in the resurgent public debate on this method of constitutional interpretation. How do we identify the nation when we are determining “roots” and “traditions”?

In constitutional lingo, who are“We the People”? The trending strict approach to originalism views the nation in a way that assumes each year of American history deserves equal consideration — and, in observed use, the court’s decisions are elevating the cultural norms of the deep past over the present. It is as though the nation is something that mostly existed long ago.

Leaving aside the merits of any recent decision, that ultra-restrictive approach rests on weak quantitative analysis. The nation in terms of its measured population is overwhelmingly dominated by American lives from modern times.

If we look to census data, we can see that the country’s annual population is roughly 14 times greater in total (adding up all the years) and 17 times greater by average (each year) for a “modern era” between 1954 and 2022 when compared to “early years” from 1787 until 1868. These are sensible periods to compare. The modern era starts with the court’s fundamental rights decisions beginning with federal school desegregation in Washington, D.C., (during Justice Brennan’s tenure), while the early years run from the Constitution’s ratification up to the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment (which applied the bill of Rights to the states).

Even if we compared the modern era to all the years that preceded it, the modern era still dominates by double the total and five times the average, and for only one-third the span. The nation over the course of history thus consists of a far greater number of modern-era Americans than from any earlier days. All years of our history, therefore, should not be valued equally when gauging our fundamental rights. While the past certainly matters, a more appropriate approach to considering “history” and “tradition” should give the modern era far greater import.

Population data is no doubt imperfect, but it is perfectly fine for these directional points. And the Constitution itself requires a census. The primary justification for the strict originalist approach is that it supposedly prevents unelected judges from “discovering” new rights against popular will. But judicial insulation is a key part of our constitutional structure. And the super strict originalist philosophy is really the one that poses a greater problem from the unelected —namely, deceased predecessors from centuries ago elected by no one in living memory.

We were gratefully born under the Constitution’s brilliant structure, but it directs nothing about its proper interpretative method. We get to choose. The restrictive way that this version of originalism is being used shackles today’s electorate to the perceived will of ancestors who constitute a very small proportion of the nation in an a historical sense — and many of whom held views that would render them unelectable today.

For most of our history, our court surveyed the past for input, not command. The application of originalism that truly cements and limits fundamental rights to our earliest history gained dominance only this summer. It ought to be short-lived. We have advanced in more than just science and technology. Our understandings in human equality and dignities have progressed far beyond archaic misconceptions.

As Justice Brennan put it, “The genius of the Constitution rests not in any static meaning it might have had in a world that is dead and gone, but in the adaptability of its great principles to cope with current problems and current needs.

”From the data, we now see that a proper analytical assessment of the nation — of We the People — for determining fundamental rights should value today more than yesterday.

* John J. Hamill is a trial lawyer from Chicago and a member of the Irish Legal 100. Follow him on Twitter @jjh349 and at jjhamill.medium.com.

Comments