Here's why "The Quiet Man," one of John Ford's most popular films, endures to this day.

The late great Maureen O'Hara's most famous film, John Ford's "The Quiet Man," constantly turns up on TV channels like Turner Classic Movies, especially around St. Patrick's Day. The film has been a St. Patrick’s Day staple for over 60 years now.

And for just as long, the film has had its detractors – those who grumble that the film is little more than a brightly-colored jaunt through Irish stereotypes: the drunks, the brawlers, and all those freckled redheads.

Well, I have some bad news for the haters. "The Quiet Man" is growing in stature, not merely as entertainment, but as a work of art.

The sign of any great, enduring story is that it can be re-imagined and reinterpreted by younger generations. And so, "The Quiet Man" – for all of its legitimate flaws – is going to be with us for many more St. Patrick’s Days.

Martin Scorsese, who’s got tons of cinematic street cred, to put it mildly, once said "The Quiet Man" was a major inspiration.

"The Quiet Man" re-imagined in Roddy Doyle's novel "The Dead Republic"

But the most interesting new take on "The Quiet Man" is Roddy Doyle's 2010 book "The Dead Republic."

Doyle is one of Ireland’s more famous contemporary writers – his book "The Commitments" went on to become a classic indie film, while his novel "Paddy Clarke Ha, Ha, Ha" won several major awards.

One of Doyle’s last projects was a trilogy of Irish historical novels based around the character Henry Smart, a sort of Irish Forrest Gump, who floats through the country’s history and has a knack for being at the center of key events.

In the first two books, "A Star Called Henry" and "Oh, Play That Thing," Henry rose from the Dublin slums to become a leader of the Easter Rising, before traveling to New York and Chicago to rub elbows with gangsters and guide the career of a young musician named Louis Armstrong.

One of Doyle’s key aims here is to reexamine Irish American history. Believe it or not, this has made him some enemies.

Traditional historical writers such as Morgan Llywelyn believe Doyle is playing fast and loose with the facts.

The problem is, history is more than just a collection of facts. So, Doyle feels free to have some fun undermining readers’ conventional wisdom about the past.

“IRA consultant” on set of a famous Hollywood movie

In Doyle’s 2010 book "The Dead Republic," Henry Star finds himself on the set of a film with Henry Fonda and the irascible Irish American director John Ford.

They are shooting a western, but Ford desperately wants to make a movie about Irish rebellion. So, he has hired famous rebel Henry Smart to serve as “IRA consultant.”

But what began as a gritty tale of Irish liberation gets crammed into Ford’s myth-making machine and what emerges, instead, is what some believe to be the worst piece of paddywhackery Hollywood ever produced – "The Quiet Man."

Along the way, Henry Smart sees that Ford is transforming the story. “All references to the war and the IRA had gone. The Sean in the picture wasn’t a kid of the Dublin streets, and all the killings had become one big punch in a boxing ring,” writes Doyle.

But Doyle is not merely lamenting the whitewashing of Ireland’s past. He is examining the deeply complicated way myth and reality collide. How complicated?

Well, if it seems like an “IRA consultant” for a Hollywood movie is a priceless slice of Doyle’s imagination, guess again – Ford’s film, indeed, had just such a hard man on set, the Irish Civil War veteran Ernie O’Malley.

And that begins to explain why "The Quiet Man" endures. For all of its donnybrooks and thatched-cottage charm, there are deep, violent undercurrents in the film.

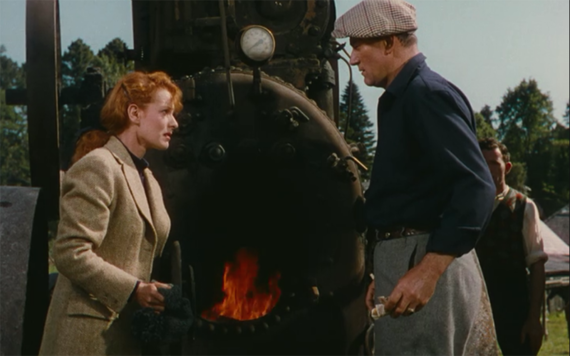

Maureen O'Hara and John Wayne in a still from "The Quiet Man."

As Professor Luke Gibbons has written: “'The Quiet Man' bears out the Celtic stereotype that, in Ireland, the tear and smile seem twin-born, and comedy is shadowed by tragedy.”

Is that why millions love the film? No. Many, indeed, love Barry Fitzgerald’s drunken shenanigans. But such stuff cannot carry a film for decades.

So give "The Quiet Man" another viewing. And really watch it this time. You might be surprised.

* Originally published in 2010. Last updated in July 2023.

Comments