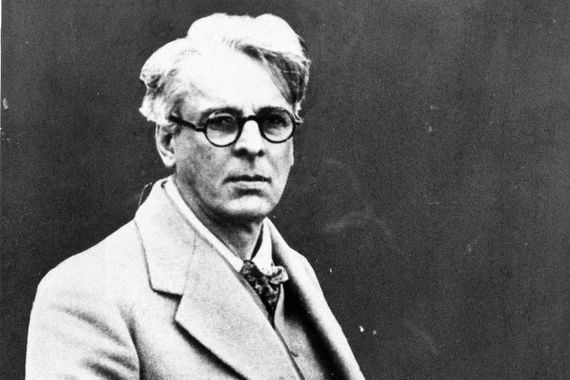

The poem that defined the era of the Easter Rising is "Easter, 1916" by William Butler Yeats. Here, Irish Ambassador to the US Daniel Mulhall explains in an essay who are the unlikely heroes Yeats is memorializing.

Yeats's great poem 'Easter 1916' is not a bad place to start when seeking an understanding of that transformative era for modern Ireland. Yeats, writing in the immediate aftermath of the Rising, spotted that Ireland had been 'changed utterly' by the events of Easter week. His description of the Rising as 'a terrible beauty' summed up his ambivalent attitude as did his question:

Was it needless death after all?

For England may keep faith

For all that is done and said.

This is a reference to the promise of Home Rule for Ireland at the end of the war and Yeats wonders if the 1916 leaders had perhaps sacrificed themselves needlessly. During the intervening 100 years, the rights and wrongs of the rebellion have been much debated in Ireland.

At the end of the poem, Yeats names some of the Rising's leaders and predicts that:

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

they would be 'changed utterly'.

Non-Irish readers of Yeats's work must wonder when these people are - the 'vivid faces' encountered in the first verse, the four individuals described in the second verse and the names that ring out from the poem's final stanza:

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse.

At the beginning of the poem, Yeats recalls meeting these ‘vivid faces’ coming 'from counter or desk among grey 18th-century houses’, people with whom he had exchanged ‘polite meaningless words.’

His first subject, the woman whose days he thought were spent 'in ignorant goodwill' is Constance Markievicz, a member of the aristocratic Gore-Booth family from County Sligo. Yeats had known the Gore-Booth sisters, Constance, and Eva (writer, suffragette, and trade unionist), during his visits to his Sligo grandparents. In a later poem, he remembered their youthful grace and beauty.

The light of evening, Lissadell,

Great windows open to the South.

Two girls in silk kimonos,

Both beautiful,

One a gazelle.

Countess Constance Markiewicz

He contrasted these fond memories of the sisters with their later lives, 'conspiring among the ignorant' and dreaming of 'some vague utopia'. In his attitudes to women, Yeats was a man of his time and could not understand what drove the sisters to turn away from the world of privilege into which they had been born in order to take up the cause of the poor and the dispossessed.

During the Easter Rising, Constance Markievicz, who had married a Polish Count, was part of the group of Citizen Army members who took over the Royal College of Surgeons. She was condemned to death but escaped execution because the British authorities were reluctant to consign a woman to the firing squad. She went on to be the first woman ever elected to the British Parliament but refused to take her seat. Instead, she was part of the first Dáil that met in Dublin in January 1919. Markievicz opposed the Anglo-Irish treaty and ended up being elected as a member of Eamon de Valera's Fianna Fáil party, but died in 1927 before she could take her seat.

The man in 'Easter 1916' who 'kept a school/and rode our winged horse' was Patrick Pearse, President of the Irish Republic proclaimed in 1916. Pearse's route to republicanism ran through the cultural nationalism that flourished in turn of the century Ireland. From an early age, he was an enthusiastic member of the Gaelic League and became editor of the League's journal, An Claidheamh Soluis, in 1903 at the age of 24. Pearse was a progressive teacher who favored a child-centered approach to education. His school, St. Enda's in Rathfarnham, imbued its pupils with a strongly nationalistic ethos.

Padraig Pearse.

Yeats did not rate Pearse highly, believing that he had been made dangerous by 'the vertigo of self-sacrifice. As a young man, Pearse had thought badly of Yeats, dismissing him as 'a mere English poet of the third or fourth rank', but later recognized his literary achievement and invited him to speak to his pupils at St. Enda's.

Pearse was probably responsible for much of the text of the 1916 proclamation while his complex personality and passionate rhetoric still define the Rising for many people.

Thomas MacDonagh, Pearse's 'helper and friend' was the 1916 leader for whom Yeats had most regard. He thought that:

He might have won fame in the end,

So sensitive his nature seemed,

So daring and sweet his thought.

MacDonagh was a poet and academic who taught for some years with Pearse at St. Enda's before moving on to teach at University College Dublin. Like Pearse, he was drawn into public life by his enthusiasm for the revival of the Gaelic language, which he later described as a ‘baptism in nationalism.’ He joined the nationalist Irish Volunteers when they were set up in 1913 in order to fight for Home Rule and quickly became a leading figure within the organization.

Thomas MacDonagh with son.

When the Irish Volunteers split in 1914, MacDonagh sided with the minority who declined to support the British war effort. Shortly before the Rising, MacDonagh became a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and its secret Military Council which planned the insurrection. During Easter week, he commanded the contingent of Volunteers that took over the Jacobs' biscuit factory and after his surrender was sentenced to death. He was executed by firing squad on the 3rd of May, the same day as Patrick Pearse.

The 'drunken vainglorious lout' in 'Easter 1916' was Major John MacBride, a man whom Yeats had every reason to dislike. MacBride had fought on the Boer side during the South African War which meant that he was one of the few insurgents with actual combat experience. He came into Yeats's life in 1903 when he married Maud Gonne, a woman with whom the poet had been obsessed since their first meeting in London more than a decade earlier. The unlikely MacBride marriage did not last long and ended very acrimoniously. In the circumstances, it was generous of Yeats to lionize MacBride, acknowledging that he too had been transformed by his involvement in the Easter Rising.

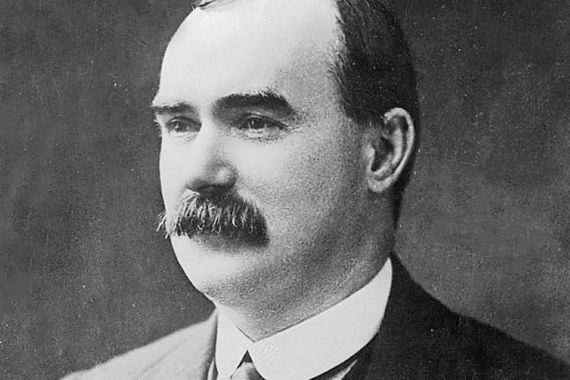

A fifth leader, James Connolly, is named in the rousing final stanza. Connolly, a socialist thinker and Trade Union organizer, is not mentioned in the body of the poem. With his conservative leanings, Yeats would not have had much time for Connolly's politics, but did recognize his importance as did Yeats's friend, George Russell (AE) who admired Connolly and felt that he had been the main inspiration behind the Rising:

This hope unto a flame to fan

Men have put life by with a smile.

Here's to you, Connolly, my man

Who cast the last torch on the pile.

James Connolly.

The fact that Yeats personally knew so many of the Rising's leaders says something about his engagement in Irish affairs in the decades before 1916. He saw himself and the literary revival he pioneered as part of the 'stir of thought' that gripped Ireland after the death of Parnell in 1891 and helped create the conditions for Ireland's transformation. Yeats fretted about the Rising’s impact on the political climate in Ireland and doubted the wisdom of the insurrection, but was moved by the courage and idealism of its leaders. He did not know what the future had in store for Ireland, but was sure that it would be very different from the past. And right he was.

* Originally published in April 2019, last updated in April 2021.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments