There is a moment in Dennis Lehane’s very good, very complicated new book "Small Mercies" in which an Irish American detective bickers with his girlfriend about the state of the world in the 1970s.

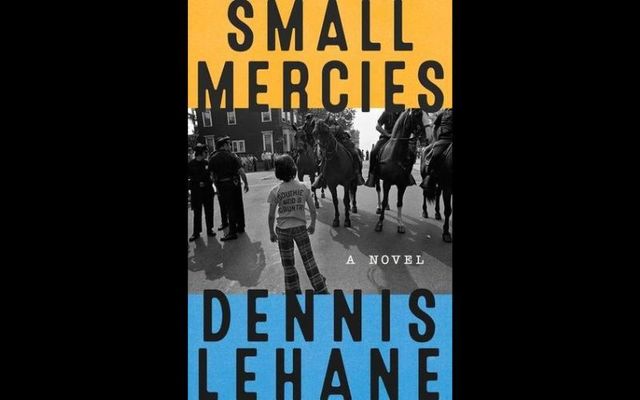

The setting is South Boston. Or “God’s Country,” according to a t-shirt worn by a defiant kid on the book’s cover.

A federal judge has decided that lots of white kids and black kids must essentially trade places – each get on a bus and go to schools outside of their neighborhoods. It is an attempt to make all the schools better for as many kids as possible.

But Irish Southie is a notoriously, um, insular place. All hell proceeds to break loose in Lehane’s book, just as it did in real life.

Lehane’s detective, Bobby Coyne, says that black students in Boston face all manner of “racist bulls***, and it’s unforgivable.”

He then adds, “But (busing) is not the solution.”

What is? Coyne’s girlfriend asks. To which Coyne replies, “I have no idea.”

This answer is at least honest.

After all, one group of people is quite newly arrived in Boston after having been enslaved and oppressed for centuries in the South. They’ve been set on a collision course with another group who were abused and marginalized on both sides of the Atlantic, but finally managed to set down some new roots in a place they call God’s Country, whatever the actual state of the actual place.

Pretending to know how to fix this would seem to be far worse than admitting that you’re stumped.

Lehane himself once said, “I believed from a very young age that all race warfare is essentially class warfare, and that it’s in the better interests of the haves to have the have-nots fighting among themselves.”

In other words, it’s hard to find bad guys to root against. Or it should be.

And yet, back then – and even more so 50 years later – so many people are so extremely confident that they know exactly who to root for and against. The more immense and complex the problem, the more confidently they cheer or boo.

Look no further than the very smart people who have praised Lehane’s novel, all the while ignoring much of what he is trying to say.

In The New Yorker, Laura Miller notes that one "Small Mercies" character has a mom who worries her child may be “too fragile” for Southie.

“You’re either a fighter or a runner,” the mom says. “And runners always run out of road.”

Yet when Bobby Coyne admits he has “no idea” what to do about the busing mess that The New Yorker calls “Boston’s white race riots,” Miller argues that Coyne “has just run out of road.”

As in, he’s running from the problem. When she should really be willing to fight for, uh, let’s go with justice.

The irony, of course, is that this is pretty much the same attitude adopted by Southie’s white race rioters. Don’t run. Don’t ask questions. Just fight.

We see where that’s gotten all of us by 2023.

Over at The New York Times, Janet Maslin writes that “like so many period pieces,” "Small Mercies" is “as much about the present as it is about the past…white, Irish American South Boston is up in literal arms about integration.”

To Maslin, this “bigotry...ought to feel dated but doesn’t.”

Uh, thanks?

Does the same go for letting the rich off the hook, while we root for or against various poor people?

For what it’s worth, vast swaths of South Bostonians behaved reprehensibly during the busing mess. Lehane makes that very clear. The reason we should read his books, though, is because that is a starting point, rather than the only point.

His harsh observations are more powerful because he knows there’s more to this story, this American tragedy, than the glib satisfaction of booing at Irish American goons.

Proper, wealthy Bostonians did that for two centuries. It’s actually one of the reasons Southie’s Irish behaved as they did.

But history is kinda dated, isn’t it?

(On Twitter & Instagram: @TomDeignan)

*This column first appeared in the May 17 edition of the weekly Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral.

Comments