Every St. Patrick's Day, the people of Buenos Aires celebrate a Mayo man, Admiral William Brown in the sun at Recoleta cemetery.

In the tree-lined passageway between the marbled mausoleums for the once rich and famous, the Argentinean naval band played "Saint Patrick's Day in the Morning" in their annual tribute to the national hero, Admiral William Brown. Brown is credited with routing the Spanish fleet in the Argentinean war of independence in 1814.

Quite how a poor cabin boy from Foxford, who first learned to row a boat on Lough Conn in Mayo, achieved naval victories to rank alongside those of Raleigh or Nelson and rose to be the father of the Argentinean navy is a fascinating story, perhaps not yet fully told.

Yet, it is a monumental example of the enduring success of the members of the Irish Diaspora. Brown's impressive green memorial occupies a prominent place in the central plaza of the cemetery (unlike that of the populist heroine Eva Peron which is consigned to a back alley).

Together, with the more than one thousand streets in Argentina named in his honor, it is an acknowledgment of the special place that Argentinean people hold for him and other Irishmen.

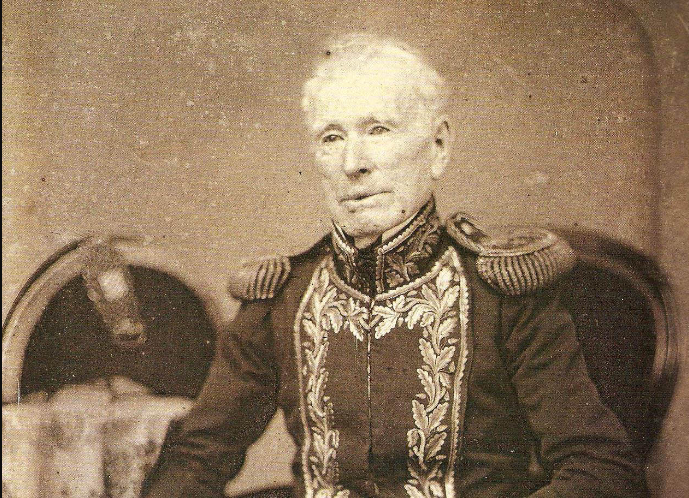

Daguerreotype of admiral William Brown during its last years. He is considered "the father" of Argentine Navy.

The links with Ireland are lasting and still vibrant today.

"There are perhaps only two hundred or so first-generation Irish living today in Argentina," said James McIntyre, the former Irish ambassador to Argentina, "but over half a million Argentinean nationals can trace their ancestors back to Ireland and that is a hugely significant number in a non-English speaking population of just over 40 million."

The main wave of Irish immigrants arrived in Argentina from the early to mid-nineteenth century. In total, approximately fifty thousand emigrants arrived from Ireland between 1830-1930.

A majority of these came from the midlands of Westmeath and Longford and from Wexford. They undertook the long journey to a mostly unknown and faraway land because they had heard about the opportunities in farming and the low land prices. ‘They worked hard and bought wisely’ said McIntyre. ‘A lot of them became ranchers in the vast fertile Pampas around Buenos Aires."

It is said that in those days the Irish owned land as vast as Ireland itself and that you could travel 200 miles without leaving an Irish-owned ranch. Some Irish ranchers became so powerful that they had towns named after them.

Unlike their fellow emigrants who went to North America around the time of the famine, the Argentinean-bound contingents were in the large part personally unaffected by the ravages of that disastrous time for Ireland but even so, coming from a poor country that was struggling against a centuries-old oppressor and the tyranny of religious intolerance, they must have been astounded by what was on offer.

Argentina is the eighth-largest country in the world. It is four times the size of France and for the new emigrants, it was wide open and beautiful. The country was booming, it was one of the ten richest on earth and the new Irish immigrants did well.

As another famous Irish emigrant, Fr. Anthony Fahy from Loughrea in Galway, who is equally memorialized in Recoleta cemetery for his work as a chaplain with the Irish communities, wrote at the time:

"Would to God that Irish emigrants would come to this country, instead of going to the United States. Here they would feel at home, they would have plenty of employment and experience a sympathy from the natives very different from what now drives too many of them from the States back to Ireland. There is not a finer country in the world for a poor man to come to."

Fr. Anthony Fahy's grave at Recoleta cemetery.

While most of the Irish remained in rural occupations in the north of Argentina, some of them ventured further south to work on the vast sheep farms in Patagonia. They profited from a special arrangement known as ‘halves’ whereby the owner of the farm would entrust say, 2000 to 3000 head of sheep to an Irish shepherd who was expected to cover all the expenses of looking after the sheep. If at the end of the period, the flock had multiplied say four or five times, then this number was divided between the owner and the shepherd.

These Irish shepherds settled in the area and became owners in their own right. In the country, the new immigrants had to fight against the native ‘Indians’ and overcome climatic conditions very different to rural Ireland.

It is hardly likely, however, that they came across the original famed giants that Magellan, the Portuguese maritime explorer who, at the service of Spain led the first successful attempt at world circumnavigation, encountered in 1520. He was so impressed with their size that he supposedly named the whole region from the word "patagon" meaning "land of big feet."

And it is when you see the wide-open spaces of Patagonia, an area of over four hundred thousand square miles almost bereft of vegetation, which in Argentina stretches from the Andes mountains to the wild Atlantic coast and down to the ‘ends of the earth’ in Tierra del Fuego, you begin to realize how challenging and dangerous the new life was for these Irish immigrants.

They would, unlike today’s tourists, not have had the time or resources to travel to see the wonderful sights of Patagonia like the Perito Moreno glacier in the south or the lakes and mountains of the Andes to the west.

Rather, they would have had to endure the hard life working as gauchos on the farms or guarding the sheep, watched over only by the soaring Andean condor in the sky and coping with the Patagonian wind, which sometimes reaches one-hundred-and-twenty-miles an hour as it roars across the plains of that semi-desert.

It was at the northwestern tip of Patagonia in Bariloche too that I stood and wondered how a small town in a strange land could name not one, but two streets with the Irish name of O’Connor and, thus, heap eternal confusion on tourists and postmen alike.

Bariloche is blessed with a splendid lake-side setting at the foothills of the Argentinean Andes. It is not unlike Switzerland but doesn’t have that same clutter or fussiness and the yodeling in the valleys. Given its location, under the shadows of a volcano, it has a deceptively genteel air in the street cafes where the locals munch creamy chocolates and sip cappuccinos.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

One of the clan, Juan, was an early settler in the area and the other, Vice Admiral Eduardo O’Connor was an explorer and revolutionary leader who was descended from an "Irish Yankee" who emigrated from Chicago to Argentina in the early nineteenth century. He too became a commander of a navy, leading the insurgent forces that fought against President Juárez Celman in 1890.

The Irish, of course, have not been slow in providing their share of revolutionaries, and the most famous and iconic (or notorious depending on your point of view) of all Argentinian rebels, Che Guevera, was born in Rosario, a city not far from Buenos Aires. His father declared "the first thing to note is that in my son's veins flowed the blood of the Irish rebels."

His grandmother was a Lynch from Galway and they were reportedly very close when Che was a child. It is sobering to think that the perennial teenage idol Che Guevara would be 94 now if he had lived and Argentina has endured a lot of turmoil and change since his birth. The Argentinean Irish have changed as well.

Back in Buenos Aires, I sought out Dr. Guillermo McLaughlin, an eminent Argentine-Irish genealogist, and historian of the Irish in South America.

Guillermo is the editor of the Southern Cross, which was established in 1875 and the oldest newspaper anywhere in the world catering for the Irish Diaspora. Guillermo is sixth-generation Irish, but is as enthusiastic about his Irish connections as anyone might be who just landed off a boat from Ireland.

He told me there were seven or eight different waves of Irish emigration, the largest of which was the arrival of the farmers from the midlands mainly in the mid-nineteenth century. He said the earliest mention of the Irish in Argentina was the record of three Galway men who sailed with Magellan in 1520 when he sailed around Tierra del Fuego.

After that there were various arrivals of ‘wild geese’ from Spain; Irish soldiers serving with the unsuccessful attempts by the British in the early 1800s to seize control of the Spanish colonies around the river Plata (many of these Irish soldiers deserted and swapped sides) and then there were the various missionaries and religious orders throughout the years and the landowners and workers and whole families who followed the first wave of settlers in the mid-nineteenth century.

"The first settlers did not integrate totally at first in the Argentine community," said Guillermo. "They had their own churches, hospitals, schools, and clubs. They did not speak Spanish but their children did and they eventually became part of the wider community while still maintaining their Irish links. You can find today, in some cemeteries in Argentina various graves with Celtic crosses and inscriptions in homage to Irish ancestors. And it is not surprising to find in some rural areas Irish descendants speaking with a notable Westmeath accent, though they have never been in Ireland and are grandsons or great-grandsons of Irish-born emigrants to Argentina."

Guillermo could not confirm what I had heard, namely that the first Argentinean officer who landed on the Malvinas in the amphibious invading force in 1982 was one of those who spoke English with a Westmeath accent, but I thought it would have been quite a shock to the British Governor of the islands as he donned his ceremonial plumed hat that morning to be told that there was a man with and Irish accent at the door telling him to pack up and clear off the islands!

Argentina, of course, has had more than its share of internal strife and violence and particularly with the 1976-1983 dictatorship and the thirty thousand who disappeared in the dirty war.

I remembered with Guillermo the untimely death last year of another Irish emigrant, the human rights campaigner Patrick Rice, from Fermoy in Co Cork, who fought tirelessly for many years as a human rights campaigner in Argentina and suffered torture, with his future wife Fatima, at the hands of the brutal military regime. As he was being released from jail, after sterling efforts by the Irish embassy officials to have him freed from near-certain "disappearance," Patrick was asked by his jailers to write something positive and he simply wrote “I might have been treated better."

I took a taxi to Plaza Irlanda, which is in the suburb or ‘barrio’ of Caballito. The driver had garish medals of the Madonna hanging from the mirror entwined with the colors of Boca Juniors, a local soccer institution. He looked to me like an evil unshaven cousin of what the legendary Maradonna might look like, and as he spat and gesticulated at the other drivers I felt I might be in serious trouble if I didn’t tip him properly.

Then I realized that he was actually pointing out the sights of Buenos Aires to me, a tourist, gruffly spitting out the names in Spanish through the open window as we careered around the hot and humid streets of the sprawling city.

It is an image of Buenos Aires and its people that remains, the friendliness and warmth of the people which lies behind their often gruff demeanor.

Friendliness is also a defining characteristic of the Irish and that would have been a good asset for the immigrants in Argentina. Plaza Irlanda is an example of how well they are still doing. In the large, tree-lined park, a haven of peace amid the bustle of the city, couples lounged together on the grass in the late afternoon shade, a group of pensioners practiced Yoga in a clearing, and a crowd of men in a clubhouse played chess. It was all under the patronage of the Argentinean–Irish society. Across the road was the Monsignor Dillon high school. Around the park were various memorials, including one to Padraig Pearse, William Brown, and a recent commemorative stone in honor of James Joyce.

Granted the original Irish have gone but there is a determined effort by their descendants to keep the link with Ireland going. At the hurling club of Buenos Aires, they are teaching young Argentineans to play the game, the original Irish schools are booming with students of all nationalities and Irish music and dancing is still alive in this city of the midnight tango.

Symbolic links are important too in this relationship between the two countries.

In 1814, William Brown a great Irishman orchestrated a monumental blow for Argentinean independence. In 1916, a small reciprocal gesture was made by an Argentinean Irishman named Eamonn Bulfin, when he became the one to first hoist the tricolor over the beleaguered GPO.

Two great countries whose histories will always be entwined have learned much from each other. When it comes to beauty, history, and national pride they are well-matched.

* Originally published in 2011, updated in July 2022.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments