"Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History" chronicles the widespread horrors of this outbreak, across the U.S. and the world.

Father Patrick Brosnan was an Irish immigrant priest who ended up serving in the Irish American stronghold of Butte, Montana.

Most certainly, Brosnan would sympathize with the thousands of people who have been diagnosed with coronavirus and those affected by the 1,000+ people who have died, as well as their family and friends.

Sadly, though, Brosnan might also point out that, now over a century on from the Spanish flu pandemic medicine has moved on.

That was not the case a century ago when, from Butte to Boston, New York to San Francisco, a different kind of virus disaster killed thousands and crippled the nation - the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918.

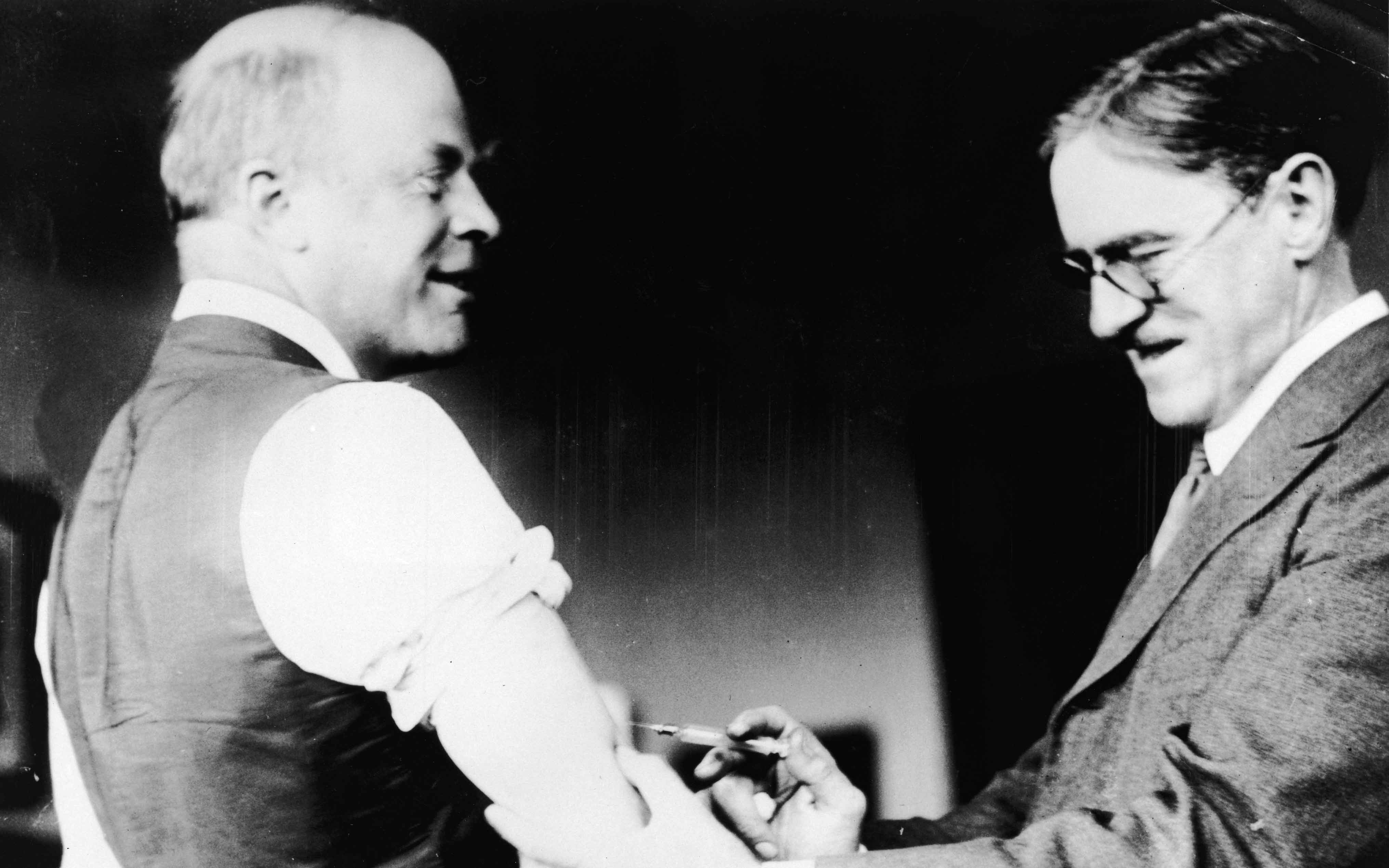

A doctor innoculates Major Peters of Boston against the Spanish Influenza virus during the epidemic, c. 1918. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

November was among the cruelest of months, forcing caregivers such as Father Brosnan to tend to the sick and dying.

“The first cases of the deadly virus in Butte … were first reported in early October,” Montana’s KPAX TV station noted.

“And then it spread just like a great blaze with hundreds of new cases every day,” added local priest, Father Patrick Berretta.

Brosnan labored to ease the Spanish flu crisis, right up until he caught the disease himself and died.

The book, "Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History" (St. Martin’s Press), chronicles the widespread horrors of this outbreak, across the U.S. and the world.

As many as 100 million people worldwide may have died from the flu, which is believed to have originated in Spain (hence its name), and was spread rapidly, in part, because of all of the troops moving across the globe during World War I.

Author Catherine Arnold describes a late September evening when the Army’s 57th Pioneer Infantry unit, based at North New Jersey’s Camp Merritt, “began an hour’s march ... to the Alpine Landing, where ferries waited to take them down the Hudson,” and off to Europe to fight in World War I.

Many of the 57th never made it that far.

“Men suffering from the symptoms of Spanish flu were falling out of the ranks, unable to keep up,” writes Arnold.

“(S)ome men lay where they had fallen; others struggled to their feet.”

Eventually, the soldiers were “followed by trucks and ambulances, which picked up men as they fell and took them back to the camp hospital.”

In the end, nearly 600 people died at Camp Merritt.

Nurses care for victims of a Spanish influenza epidemic outdoors amidst canvas tents during an outdoor fresh air cure, Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1918 (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

All of their names are inscribed on a somber, 66-foot monument in Cresskill, New Jersey, which still serves as a reminder of the terrible toll exacted by what some have called the “forgotten epidemic.”

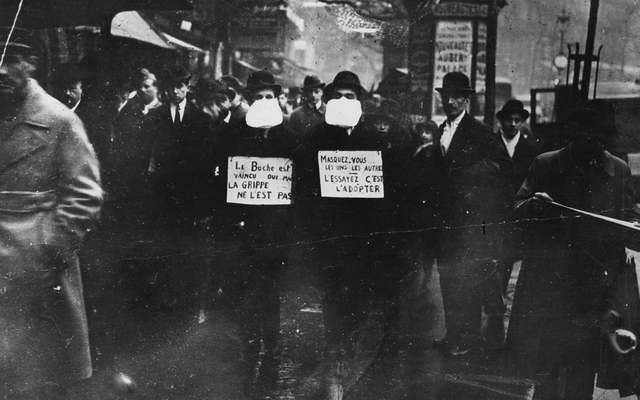

Entire cities were shuttered and quarantined during the autumn months of 1918, which should have been a joyous time. The war to end all wars—which many of the Army’s 57th never made it to—finally drew to a close in November.

And yet, the deadliest war was being fought on the home front. When all was said and done, nearly 700,000 American deaths were attributed to the deadly virus.

As were nearly 25,000 in Ireland, where theaters and dance halls across the country were shuttered, to minimize public contact and halt the spread of the disease.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Indeed, one theory holds that Irish Catholics were hit harder than Protestants in Ireland because church-going rates among Catholics are higher. Even the GAA final between Tipperary and Wexford had to be postponed.

The 100th Anniversary of the Spanish Flu pandemic has given scientists and other public health experts an opportunity to ponder not if, but when, another such deadly outbreak might strike.

“Warning,” blared a grim Time magazine cover earlier this year, “We are not ready for the next pandemic.”

When you gather with friends and family this week, give special thanks for the roof over your heads, which is so easy to take for granted. As is the clean air you breathe.

* Originally published in Dec 2018, updated in Dec 2023.

Comments