President of Ireland Éamon De Valera was made an honorary chieftain of the Ojibwe nation, in Wisconsin - a propaganda act and a message for oppressed people.

In 2018, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar made international headlines when he visited the Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma to thank them for the generosity of their ancestors, referring to the Choctaw Nation’s donation of $170 to feed Irish people in Dublin during the height of the Great Famine in 1847.

He promised to provide scholarships to Choctaw students willing to study in Ireland.

The Taoiseach was not the first man to visit a Native American nation on behalf of the Irish people, however. In fact, 2019 marks the centennial of Éamon de Valera’s visit to the Ojibwe nation (formerly commonly referred to as the Chippewa).

Read more: Choctaw Native American leads Tipperary famine walk, compares to “Trail of Tears”

Taoiseach Varadkar speaking at the Choctaw Nation. Image: RollingNews.com.

On October 18, 1919, De Valera, while touring the US as the President of the Irish Republic, was adopted as an honorary chieftain of the nation during a visit to their reservation in Wisconsin. He was named ‘Dressing Feather’ or Nay Nay Ong Abe, after a famous Ojibwe leader. The ceremony took place in front of 3,000 Native Americans and white people. The audience watched ceremonial dances and listened to a variety of speeches.

Chief Billy Boy and Joe Kingfisher welcomed De Valera to the nation and Kingfisher declared, “I wish I were able to give you the prettiest blossom of the fairest flower on earth, for you come to us as a representative of one oppressed nation to another.”

During his speech, De Valera spoke in both Irish (Gaelic) and English to highlight to common cultural oppression of both groups.

He received thunderous applause when he declared, “I want to show you that though I am white I am not of the English race. We, like you, are a people who have suffered, and I feel for you with a sympathy that comes only from one who can understand as we Irishmen can.”

Read more: Celebrating the Choctaw Nation this National Native American Heritage Month

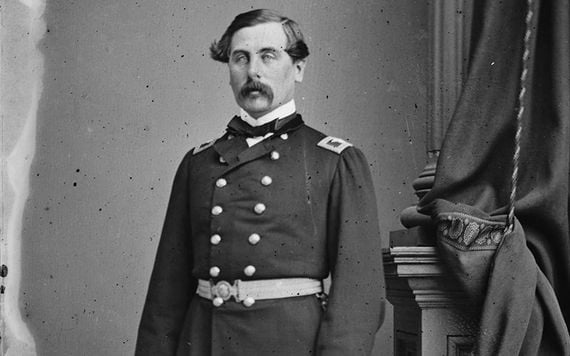

Former Irish Taoiseach and President Éamon de Valera.

These statements represented the anti-colonial and anti-imperial struggle that permeated through Irish nationalism during the early twentieth century. De Valera used his platform as a European to highlight the oppression of other disenfranchised peoples, including that of the indigenous peoples of North America.

Nevertheless, De Valera also used the trip as political leverage against white Americans who did not support the cause of the Irish Republic. De Valera had trouble gaining traction in the corridors of Washington D.C. particularly with Woodrow Wilson, a known Anglophile, occupying the White House. Dev’s reception in major cities was mixed.

In Worcester, the Mayor welcomed De Valera as a war hero and led the parade, however, in Baltimore Mayor Broening greeted De Valera cordially but refused to acknowledge him as the President of Ireland.

Moreover, Cardinal Gibbons, a known Redmond supporter, and Sinn Féin critic, warmly welcomed De Valera and spoke with him about the close link between Ireland and America. He cautiously warned De Valera that he should conduct his trip so it could be “be characterized by wisdom, judgment, and discretion so it may enlist, new friends to your cause.”

John Redmond with National Volunteers.

Gibbons had long been suspicious of Irish nationalist movements and played little or no public role in the Home Rule cause in the 1880s and 1890s, but he had grown to reluctantly support the cause of Irish freedom between 1916 and 1919.

Gibbons only began to support the Rising and De Valera after it became abundantly clear that a majority of working-class Irish Catholics in American cities had embraced Sinn Féin and the Easter Rising, which had inaccurately been attributed as a Sinn Féin uprising, despite their lack of involvement.

In February 1919, Gibbons unenthusiastically read a resolution calling on the peace conference in Europe to apply “the doctrine of national self-determination” to Ireland.

De Valera’s visit to the “Chippewa Reservation” in Wisconsin gave him the opportunity to use Wilson’s language of self-determination against him and shame Americans about their own colonial past.

During the speech, De Valera pointedly stated, “I call upon you, the truest of all Americans … to help us win our struggle for freedom.”

Read more: John F. Kennedy branded de Valera a “lunatic” after 1945 visit to Ireland

Éamon de Valera.

This statement embodies De Valera’s dual support for disenfranchised Native Americans and his desire to push white Americans towards supporting Irish freedom. His language, calling Native Americans the true Americans, instantly compared them to white Americans. De Valera believed that this language would compel the political elite in America into action as well as ensure that working-class Irish-Americans bought Irish bonds.

In 2019, during the centennial of this historic event, we should look back at Éamon de Valera’s visit to the Lac Court Oreille band of the Ojibwe as another chapter in a complex history between Irish people and Native Americans. The Choctaw provided the Irish with relief during the Great Famine in an effort to aid a colonized people.

Thomas Francis Meagher.

Irish people aided indigenous groups in the nineteenth century, yet Irishmen such as General Thomas Francis Meagher also aided the federal government in the displacement and oppression of Native American people.

De Valera’s trip to the Ojibwe nation was a propaganda piece to highlight the hypocrisy of the Wilson administration. However, it was also a genuine call to action by an Irish leader who wanted to use his new-found political platform to embrace the struggles of other oppressed peoples.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments