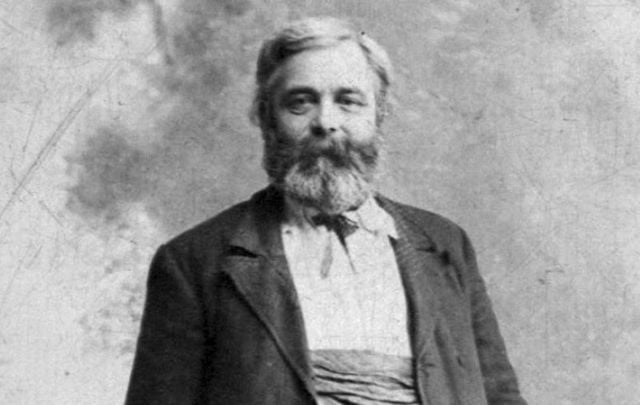

Michael Cusack was born in Carran, Co Clare on September 20, 1847, and went on to found the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). Learn below how the sports organization, perhaps the most valuable group in the State, saved Ireland during its fight for freedom

I met with Hugh McCann of the Department of External Affairs in the 1960s when Ireland was preparing to join the then-EEC. I asked him whether it was the right thing to do.

He replied: "Well yes unless of course, we want to continue supplying cheap food and labor to our neighboring island."

The island of Britain – particularly England – still looms large, but thanks to joining the EU as it now is, we no longer need to be content solely with supplying her with cheap services. The sense of nationality that gave us the courage to join the EU, and a State with which to do it, owes itself in no small part to the GAA.

The proximity of our islands means we seem destined to be entangled in Anglo-Irish knots, Brexit being the most suffocating. We now have Arlene Foster’s use of coded threatening language, warning the red lines of Unionist objection are not merely red but blood red.

However, the combination of independence, education, and a sense of race and place, enhanced so strongly by the GAA, gives us every hope that we will survive these complexities.

No observer looking at Ireland in 1884 when Michael Cusack and a handful of Fenians – with one exception, a rugby-playing inspector in the RIC – founded the GAA in Hayes Hotel in Thurles could have foreseen such promise.

The Irish landscape, psychologically and physically, could easily have been framed out of Goldsmith’s lines: "Ill fares the land... where wealth accumulates and men decay."

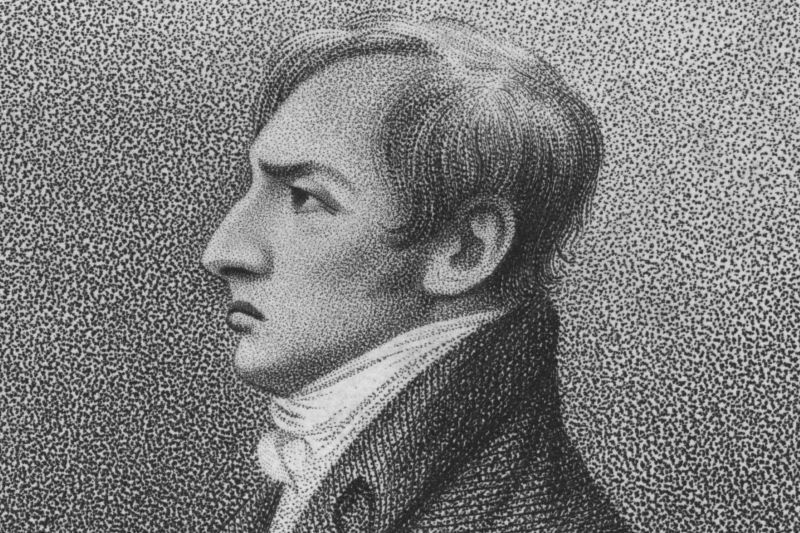

Archbishop Croke readily agreed to become the patron of Cusack’s new association because of his despair at the sight of young men hanging around with no work and little prospect of any. He rightly saw the GAA as a means of injecting energy and purpose into the youth, and of inculcating a sense of Irishness which an education system, based on teaching children that they were English, had done much to erode.

Pádraig Pearse would later say the foundation of the Gaelic League was what recreated the Irish nation.

In fact, the GAA preceded the Gaelic League by four years, and both played a part in transforming the psychological and political landscapes to a degree that is hard to grasp today.

Suffice to say that Cusack’s claim that the GAA spread like a "prairie fire" was accurate.

Initially, it began as an athletic association, with hurling and football coming along afterward. From its inception, the association inter-mingled with the physical force tradition, so the purely sports-minded members such as Cusack continuously struggled with the Fenians for control of the association.

In its early days, and indeed to the coming of the so-called "free education" in the 1960s, another struggle occupied the association: that of the power of the clergy on which the GAA was initially dependent for secretarial and organizational talent. The bishop throwing in the ball at the start of the All Ireland was an apt symbol for the other colonialism vying for Cathleen ní Houlihan’s soul against mother England – mother Church.

The Castle authorities and their agents, the RIC, correctly perceived the GAA from the start as a threat.

Bloody Sunday was no coincidence, when the Brits attacked a GAA game between Dublin and Tipperary in Croke Park, killing eleven including one of the players and injuring 60 civilians. They knew they were striking at the heart of Irish life.

The War of Independence, whose centenary is occurring, owed a great deal to the GAA, whose young men marched on public occasions with ‘Tipperary rifles’ (hurleys) on their shoulders.

The GAA produced miracles of tightrope walking between Fenians and football. After the 1916 Rising, Croke Park was used for a crucial meeting of the underground Dáil.

Croke Park.

This meeting brought the volunteers under its control. But the association could always validly point to its constitution that it was not political and was non-sectarian in outlook.

In Kerry, when the Civil War was at its grimmest, this ruling held fast, allowing Free Staters and Republicans to compete, and then melt into the crowds after the final whistle of the game.

After the war, the GAA played a major part in helping bring opposing sides together. Civic Guards played alongside active IRA men and attendance at matches gave both wounded parties a chance to participate or to watch sports while allowing wounds to heal.

Unfortunately, the seepage of historical poison made the GAA a target for sectarian assassins when the Troubles broke out and the H-Block controversy almost tore the association asunder in the North.

Somehow the vision of Cusack and Croke persisted – the association remained united.

But the tensions and shadows of the past still hover. The Kingspan rugby stadium and the Windsor Park soccer mecca thrive after rejuvenation. At the same time, a proposal to revivify Casement Park was launched. Alas, Casement Park lies derelict and weeds, not footballs, cover its surface.

Such are the twists of history that still influence Ireland in the anniversary year of the War of Independence, and which arguably make the GAA the most valuable organization in the State.

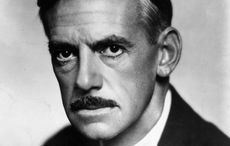

* “The GAA and the War of Independence” by Tim Pat Coogan is published by Head of Zeus and is available on Amazon. Tim Pat Cogan is Ireland’s leading historian who has written definitive biographies on Eamon de Valera and Michael Collins among others.

* Originally published in 2018, updated in 2025.

Comments