Going on a genealogical quest in County Meath, from the Great Hunger to Maureen O'Hara, "The Big House" and scandals.

My wife and I recently brought back relics from Ireland. The small worn head of the Virgin Mary now rests on my bedside table. A faded, hand-painted portrait of St. Joseph with the Christ Child hangs on the wall. They came from the farmhouse in which my great-great-grandfather Michael was born a hundred and 75 years ago.

Over a nine-day journey across the island this March, my wife and I made new relationships with the people, with the country, and with our own histories. So the icons are more than simply religious.

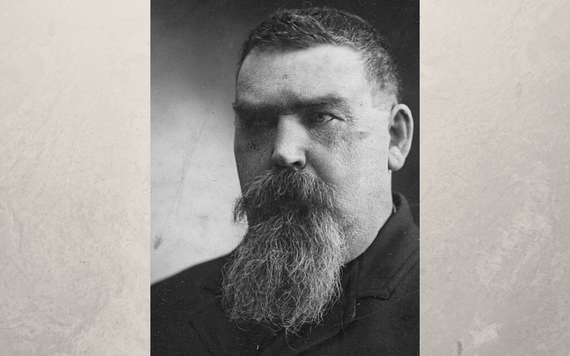

Author’s great-great grandfather, Michael Carolan, a blacksmith, born in in Springville, Co. Meath, on July 24, 1844. He died in Philadelphia in 1906. His wife Annie gave birth to 17 children; six lived into adulthood. Credit: Ann Marie Carolan Moerk

They symbolize our stories, which, like most immigrants from distant shores, are by turns heartbreaking, complicated, and full of longing. The common narrative is one of generational exile and abandonment through pressures of church, state, and society.

My wife’s family was forced to quit the country and give up their children. My own family fled during one of the world’s greatest economic and environmental health disasters of the time. The Great Hunger killed a million people and sent another two million across the seas.

With the unprecedented health crisis surrounding us today, history does not seem so far away. Our son, home from college early, looks at the old framed portrait I brought back. I tell him that it was found in the birthplace of our Irish ancestor. We also have ancestors from Lithuania, Switzerland, and England.

“Really?” he asks. “How lucky is that.”

Before my wife and I left on our trip, I contacted a town historian in Kells, County Meath, which is about an hour north of Dublin. He offered to help in my genealogical quest and so when I arrived, I rang him up. Willie Carr has white hair, worried briefly about the possibility of rain, and chuckled easily.

Home, Springville, outside of Kells, Co. Meath, in the 1950s. Carolans were born here in the 19th century and 19 Brady children were born here between 1906 and 1957. Credit: Conor O’Brádaigh

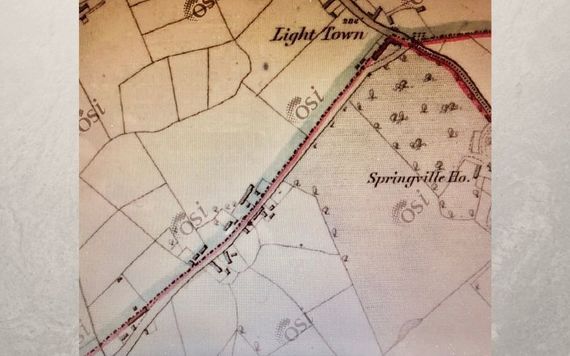

“Welcome to the auld sod,” he says. He knows from our email exchanges before the trip that I have years of yarns, of searching maps, censuses, baptisms, marriages, deaths, and ancestry.com behind me. He drives us to a place with two names—Springville and Light Town—so named for the candlelight that once emanated from the foot-square windows of the former houses there.

Read more

Three men stand in front of a two-story, boarded-up house. Willie introduces us—Patrick Brady is a tall, retired farm equipment salesman, his brother Johnny, a former politician with the Dáil Éireann, lives in a house a hundred yards away. His son Conor is clean-cut and works at a local high school in Oldcastle.

Conor and Johnny Brady at Johnny’s birthplace, Springville, Kells, Co. Meath, March 1, 2020. Credit: Michael Carolan

He spells his surname in Irish—O’Brádaigh—and points to a sentence in a genealogy. “Mary married a Carolan and was a farmer in Springville.”

Springville & Light Town, Burry Parish, Union of Kells, Co. Meath, 1837, showing house and barns of author's ancestors in lower left corner. Credit: Ordnance Survey Ireland

Turns out that the Carolan whom Mary married is my cousin Bryan, from four generations back. Mary’s brother Tom helped tend the farm. Tom married and raised 10 children there. His son Patrick raised 11 children, all born in the house, including the two brothers standing before me.

Mary Connor Brady, Johnny’s mother, with Maureen and Thomas, about 1939. Credit: Conor O’Brádaigh

Next to the house are two gabled barns of cut limestone, shimmering brown-green in the afternoon light, emerging from soil as naturally as trees. There’s a wall and a gate framing a small yard that opens on the lane. The house is plastered grey, with a central chimney, seven windows and a porch sheltering the front door.

It was the home of a middle-class farmer, Willie says, built by the landlord for a valuable employee such a blacksmith, which is what the Carolans were. Inside it’s dark; the wallpaper is peeling, a stairway leads to the second floor where light is spilling in from holes in the roof.

Mary Connor Brady with Maureen, Rose, Thomas, James, Patrick and Daniel, about 1943. Credit: Conor O’Brádaigh

In a bedroom, I find the small head of the Madonna. The dusty framed print of Joseph is leaning against a wall. Outside the house in the sunlight, I hold them up. The brothers grin. “Our mother’s,” they say. “Take them, take them.”

Across the horizon beyond the house, a rainbow appears. I have my wife smile for the photograph and she beams.

Ruth at Springville, Kells, Co. Meath, March 1, 2020. Credit: Michael Carolan

The Big House

Later Willie drives Johnny, his wife Kathleen, my wife, and I to a churchyard on a solitary hill in the middle of a broad windswept plain. There’s high, weathered stonewalls—the ruins of the former Burry Parish chapel, dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Catholics buried here are separated from the Protestants by a ledge. The Carolans are on the lower ground; many used wooden crosses that didn’t last.

Willie points out a headstone that shines, new and polished. Fitzsimons was the grandfather of Hollywood legendary actress Maureen O’Hara. She made a ceremonial visit here in 2012 at age 92. I imagine the scene suddenly: townspeople wheeling the graceful, elderly redhead across the field and up the hill to pay her respects to her relations.

“Your people are related to her,” Willie says, reminding me of the record he found—the Kells parish priest writing in the register that my uncle who remained, Michael, married Ms. Bridget Fitzsimons on July 23, 1833.

The graveyard is part of the Balrath Bury Estate of the Anglo-Irish Protestant landlords. Generations of Carolans and the Bradys paid rent to them. Willie tells us that for the first time ever (since 1671) Catholics live in there.

Cemetery, Balrath Demesne, where author’s ancestors are buried. In 2012, Hollywood legend Maureen O’Hara, at age 92, visited the headstone of her grandfather here.

“Moving up in the neighborhood,” I joke. Kathleen laughs and says, “By degrees, slowly but surely, we are.” Religion is one of the eternal divisions here, mirrored in the estate walls that roll across the emerald fields of County Meath.

Turns out that Willie contacted the owners, who invite us inside the Balrath House. The owner’s wife greets us, apologizing for being called away. Everyone seems to know one another. A gracious short elderly woman named Eileen serves us tea. Her husband Joe, who passed away last winter, worked here most of his life.

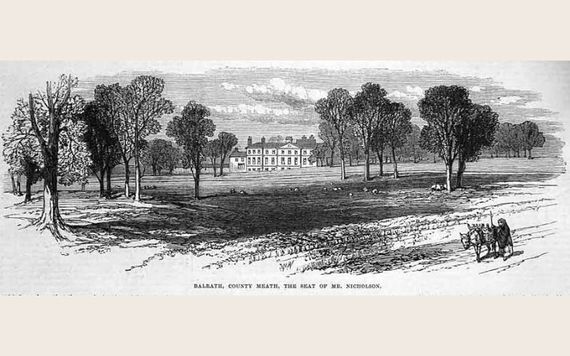

The place today is a two-story, 18th-century colonial revival villa that has been scaled back. An old swimming pool fills the yard where a wing had been removed. This Big House is like many others across Ireland now—decaying testaments to an earlier age.

During and after the Great Hunger, the landlord, John Armytage Nicholson, cleared land for grazing more cattle. Two decades on, Springville’s population had dropped a whopping 80 percent, according to the census.

Impoverished, rent-paying tenants there for generations were furious. An attempt was made upon Nicholson’s life. “It was said that the landlord switched seats on the ride out to the estate,” Johnny told me earlier. “So it was the driver who took the bullet, not the landlord.” Nicholson and his niece were wounded, the carriage driver died.

“They say that near the end of his life, the landlord put a sick lady out into the road,” Johnny says. “The priest went to ring the bells in the parish, and it was said that Nicholson couldn’t get the ringing in his ears to stop, went mad and died.”

Inside the Nicholson Estate, we are shown the dining room, its sculptures, paintings, and Georgian furniture reminiscent of long-gone inhabitants who once stood among the power elite of Anglo-Irish society. Think interiors of Downton Abbey a hundred years on. Nonetheless, Kathleen Brady suggests my wife and I descend the spilling stairs so she can snap a photograph.

We smile big.

I am reminded that I come from people, with very little, who left this life for America, in the middle of an immeasurable disaster, who were ostensibly evicted by the one-time overlords in whose home I now stood, and to make room for what was it? More cattle?

That immigrant’s grandson—my paternal grandfather—sold bread door-to-door at age 14, saving enough pennies to attend Philadelphia’s Drexel University. He went on to build a successful engineering firm in Missouri, where I was born. I think how lucky I am to be helping the fourth generation of my family to receive a college education.

To the West

On the way, we stop at Strokestown Park and the National Famine Museum, in County Roscommon in the middle of the country. We learn that thousands of orphaned girls were sent to Australia to be adopted into families there, which brings us to my wife’s story.

The author and Ruth in the one-time home of the landlord to whom generations of ancestors paid rent in Ireland. Credit: Kathleen Brady

Ruth was adopted, at six weeks old, and raised by a loving family in Rhode Island. She has naturally wondered over the years about her birth parents but never went looking them. Last summer I discovered that one’s real birth certificate, not just the adoptive one, could now be obtained in Massachusetts. It arrived and named her mother, whom we quickly discovered had passed away, but who also had another family after Ruth’s birth.

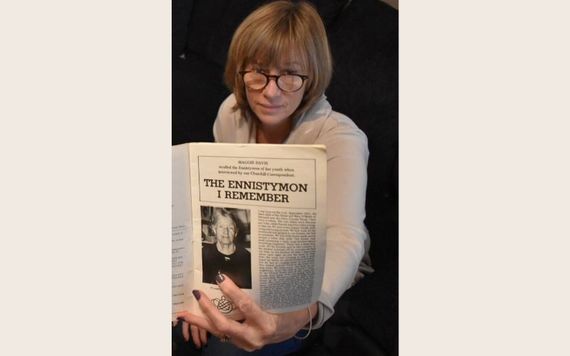

Ruth contacted and met her half-sister who provided much information. Turns out that Ruth’s maternal grandmother was born in Ireland and left for Providence, RI, at age 18, where Ruth’s mother was born. The story went that Ruth’s mother Sandra had been told by her mother, Lena, that her grandmother in Ireland, Maggie, died when young. Suspicious that she was lied to, Sandra sent a friend in the 1990s. The friend went to see the village butcher, where she inquired about Maggie. There she discovered that Maggie had lived to be 103 and only recently died.

Balrath-Bury House and Estate, from April 25, 1870, issue of London Illustrated News in article about the assassination attempt made on landlord John A. Nicholson. Credit: London Illustrated News

So when my wife and I arrived in Ennistymon, a picturesque village not far from the spectacular Cliffs of Moher in County Clare, we were excited. We started with the butcher, naturally, and after one connection led to another, we found ourselves at a door.

A young, bald man answered. He has my wife’s eyes. Ruth tells him the story of their connection—that she believes their great grandparents are the same. That they didn’t have 9 children but had 10. That their first child, Ruth’s grandmother, had two children, one of whom was Ruth’s mother. To prove it, her grandmother’s obituary in the Providence Journal named her parents as Maggie and Patrick.”

Ruth Carolan with article written by her great grandmother, who does not mention her first daughter, born out of wedlock, who immigrated to Boston, then Providence, in 1927. Credit: Michael Carolan

“Those are my great grandparents,” Patrick says, laughing. “They lived right here. That’s crazy. It’s cool.” He looks at Ruth. “You are literally a relative as much as any of my cousins are.”

She explains that Lena was pregnant at age 18 and was likely forced by the Church to emigrate. After she gave her baby up, she married and had children and her daughter, Ruth’s mother, repeated the cycle. “It’s amazing that no one could not have sex,” Ruth says. “No one could meet that requirement of the Church.”

“It’s madness,” Patrick says. “That sex is such a part of life, married or not. And what happened to our great grandparents was very hush-hush. A sin. They take your child because you weren’t worthy of bringing up the child. Tough times, they were. Very cruel.”

I ask if he wants to visit the States. He says he might come but no time soon: rumor is that a doctor in the village recently returned from Italy with the coronavirus. He asks about our lives. The cycle of abandonment has stopped, for now, we joke.

When we married on March 21st, 22 years ago, with our families as witnesses, we were three months pregnant with our son. Our daughter was born a couple of years later.

We’ll keep them as close to home for as long as we can.

* Michael Carolan is a Professor of Practice in the Department of English at Clark University in Worcester. He lives in Belchertown.

Comments