In the latter half of the 19th century, thousands of Irishmen made their way to Butte, Montana, in the U.S.A’s isolated far north-West, searching for a better life.

Some made the six-day journey from the coal mines of the eastern States, and the mid-west. Others came from the mining camps scattered throughout the west, to work in the copper mines of Montana’s inhospitable Rocky Mountain region. Many prospered, though thousands lost their lives or were maimed in what became known as the “Richest Hill on Earth.”

Among the wave of souls who made their way to Butte were my grandfather, his brothers, and sisters, who hailed from Edrim Glebe, Killymard, Co. Donegal. Pat, John, Hugh, Manus, Annie, Winnie and Catherine (Kate), who were all sons and daughters of Patrick and Sophia Carney Sophia of Edrim Glebe, Sophia (nee Ward), hailing from Letterbarrow, made the long journey to Butte just before the turn of the 20th century and were pioneers of the town.

Throughout the 1990s I had been researching and corresponding with great uncle Hugh’s surviving relatives and others in Butte.

In 1998, my two sisters, Sheila and Patricia, and I, decided we must pay the town a visit. On hearing of our plans, our cousin Tommy Quinn, who also has Quinn cousins in Butte, decided he would come along too.

Butte is still a very Irish town with all the old mining pioneer names still in existence. Butte’s residents are still attached to their Irish culture, and indeed many of its second and third-generation Irish, still maintain strong family links with Ireland.

Being brought up in an Irish coal-mining community in South Yorkshire, England, my sisters and I found much in common with the people of Butte, especially since our dad had been a miner of long standing. He spent 40 years working 3,000 ft underground day-in day-out in the coal mines with his west of Ireland mates, and the job took its toll on them all.

It was he who initially sparked our interest in Butte, as he often related tales to us about his dad and uncles and aunts when we had a few pints.

My had grandfather returned to Donegal in 1914, fully expecting to return to Butte with his family to start a new life. However, tragedy struck again in the form consumption when his daughter Sophia died in 1916, aged sixteen. In 1923 my grandmother Mary, nee Sweeney, originally from Drumkeelan also died of the merciless disease.

As we would learn, his siblings back in Butte suffered still more strife and tragedy.

How Butte Became Irish

In the Montana-Territory, in what is now the State of Montana, prospector William, L. Farlin discovered encouraging deposits of rich mineral in his shallow diggings.

After having them assayed in neighboring Idaho, they were found to be rich in gold silver, and copper. Farlin kept his discovery a secret and, being without capital to exploit his find, continued making a modest living working his shallow diggings.

But Farlin never forgot the fact that mineral-bearing quartz lay under his workings. Several years later, in 1874, Congress passed a law compelling owners of claims to perform a certain amount of work or forfeit their claims by January 1, 1875. Farlin relocated his claim and commenced development work in the freezing Rocky Mountain location.

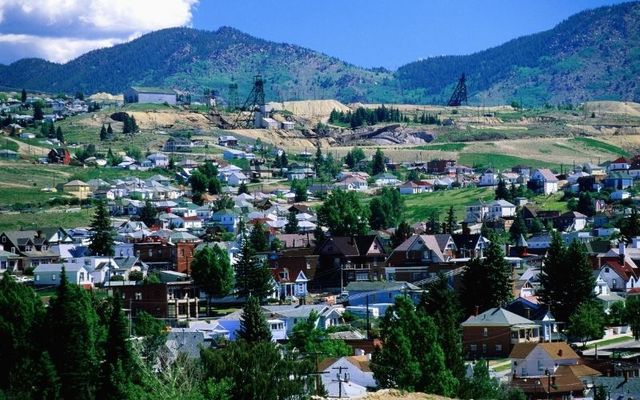

From a mediocre prospecting camp full of tents and rough shacks, Butte, as it was known (named after a mountain peak that stands northwest of the prospecting town) in three months became the most significant silver mining camp in Montana Territory.

News of the camp’s potential spread like wildfire, and soon Butte echoed to the sound of pick and shovel. A 19th-century writer described the camp as a “rough deplorable conglomeration of log cabins, shanties, tents, saloons, and livery stables where no man was safe without a revolver in his belt and a bowie knife tucked in the calf of his boot.”

Irish miners from the Mother Lode mines of California, from the hard-rock mines of Nevada and Colorado, and from the copper mines of Michigan, were among the new arrivals in Butte, along with “greenhorn immigrants” from Ireland. The majority of skilled miners were originally from the parishes of Eyries, Hungry Hill, and Berehaven, West Cork. Men from that area had long experience of mining from the area’s then redundant Puxley-family-owned copper mines (famous in Daphne du Maurier’s novel Hungry Hill), which forced thousands of West Cork men and women and their families to emigrate, with many ending up in Butte. Father Patrick Brosnan, a Butte priest from County Limerick, wrote back to his father that “Everyone here is from Castletownbere---Butte is a great city, we have seven fine Catholic parishes. ” He must have felt that he was in Castletownbere, too, as the most common name in Butte’s Polk directory was O’Sullivan.

Butte quickly grew from a small mining camp to an industrial town with 300 mines operating within the town’s boundary. The rip-roaring frontier town became fondly known as “Hell Roaring Gulch.” The town never slept and had the reputation of being the toughest town in America. It had saloons, as well as gambling joints, dance halls, theatres, Chinese wash houses, restaurants, and shebeens, such as Dublin Dan’s infamous Hobo-Retreat. All were open 24hours a day.

By 1900, half of Butte’s 30,000 population were Irish; Butte’s, suburbs were named Hungry Hill, Dublin Gulch, and Cork Town. Irish societies flourished too, with the Clann na Gaels, the Gaelic League, the Parnell Guard, the Emmet Guard, Daughters of Erin, the Robert Emmet Literary Association, and the Ancient Order of Hibernians. The G.A.A flourished too with the Butte-Based Wolf Tones and the Emeralds of nearby mining town Anaconda, according to one report many a fierce after-match battle took place between Butte’s miners and Anaconda’s smeltermen.

Butte had eight Cork-born mayors; the Irish ran the police, the fire, and education department, the attorney’s office, and the district coroner’s office. There were numerous Irish judges, mine superintendents, shift bosses, mine engineers, and officials, and of course there was the god-like, Marcus Daly. There were seven Catholic churches, built mainly through miners' donations and their own labor. The town also had three Irish newspapers----the Rocky mountain Celt, the Irish American, and the Irish World. There was also an Irish brewery, and Guinness was also on tap in Butte’s saloons.

Many Irish politicians visited Butte on fundraising trips, including Countess Constance Markievicz, Douglas Hyde, founder of the Gaelic League, and first president of the Republic, also Michael Davitt, James Connolly, Eamon de Valera, and Mountcharles-born writer and story-teller Seamus Mc Manus. Butte’s miners were the most generous in the United States.

Butte’s mines also had a notorious reputation as the most dangerous in the world. The life expectancy of a miner being just 10 years. Saint Patrick’s and Holly Cross, cemeteries were the largest cemeteries per head of population in the United States. The town's daily newspapers made grim reading, with headlines such as “blown to bits, legs torn off, crushed, scalded and blinded. Miners blamed accidents on company profit being put before safety.

Nevertheless, Irish miners kept their sense of humor. A fall of rock was a ‘Larry Duggan’ named after Butte’s Irish undertaker. Excessive coughing or miners' consumption caused by the mines' toxic dust was known as the ‘giggles.’ As in all Irish communities, fundraising dances and socials were organized to ease the burden of accidents or death. Stalwarts amongst the Irish societies were the Robert Emmet Literary Association, and the Ancient Order of Hibernians, both of which had relief programs. Members could expect several weeks’ wages if sick or injured and lump sums in the case of death, payments were made to wives and children.

In the center of Saint Patrick’s cemetery stands a 20ft granite obelisk erected by Clann na Gael, it is decorated with harps and shamrocks, and acts as a lone sentinel for the men and women who forged new lives out of the western wilderness.

Read more

What Happened to my Ancestors?

The Carney siblings, from Edrim Glebe, Donegal, settled in Butte, with the men working in the mines. But as my sisters and I would learn, some of their new lives were cut short.

Newspaper clippings from local Butte papers of the day revealed their fates.

The first loss for the Carney family was Pat, the eldest, and under very mysterious circumstances.

Tragedy hits Edrim Glebe family

Eldest son of Sophia, and the late Patrick Carney, shot dead in gunfight.

Butte Intermountain news September 13th, 1902

Shot Carney in self-defense

John Taylor, watchman for the Montana Ore Purchasing Company, shot and killed Pat Carney of Toboggan Avenue, Walkerville at the Cora mine yesterday afternoon at 3 0’clock. The story of the shooting from the lips of Taylor, who is now in custody pending investigation, is as follows. “Paul Hudliff a shift boss at the Cora, told me that Carney, had been there and hit him in the head with a rock, this happened in the forenoon. Carney said at the time he was going to get a gun and kill everybody in sight. I went over and sat on a pile of timber and began talking to the day watchman. Suddenly a bullet came whizzing over our heads. The teamster of the Cora came running up to me, and said:

“Here’s a man with a shotgun coming. He is shooting at me and trying to kill me”.

“I went round the pile of timber and faced Carney, about 20ft away. Carney was holding the weapon in a threatening manner. I yelled to him to drop the gun. He had an old Winchester rifle. And, as I spoke, he blazed away. He kept shooting until he had emptied his gun. After the first shot his movements were rapid and he got behind the timber firing five shots at me. The company team and the timber prevented my receiving a serious wound. I could not get a chance to shoot either for fear I would hit one of the horses or some of the men. I had a six-shooter in my pocket and took it out when Carney began to blaze away”.

“My first two shots went wild. The third hit Carney in the head and he fell dead instantly without a groan. I was sorry to have to shoot so close, but it was a matter of life and death as he was pegging away at me all the time, and might have given me a fatal shot any minute.”

The jury heard that Carney had been none too well since returning from Ireland.

Deputies were after Carney

Deputies were on the track of Carney when he was killed, after the man had beaten up shift boss, Hudliff, and J.P. Sullivan, a day watchman at the Cora. Yesterday forenoon, Taylor, who is also a watchman, came downtown to the office of the County Attorney Lamb and swore out a warrant for Carney’s arrest.

Taylor feared trouble and had armed himself accordingly, as Carney, had openly boasted that “he meant to clean up the ranch.” Taylor came downtown again and gave himself up surrendering to Under Sheriff McGuigan at the courthouse.

At 5 0’ clock Coroner Johnston had been notified and was on his way to take charge of the body which lay where it fell.

Possible motive for crime

There is little doubt that Carney was insane. The only possible motive to be assigned to Carney, in his efforts to kill Taylor and wipe out the entire force up at the Cora, was animosity rankling in his breast on account of an old grudge he had against foreman Burlington of that mine. They had some trouble some months ago over a contract. Carney claimed he was to have been paid $5 a day for a certain piece of work, which, when it was completed, Burlington allowed him only $3. Carney was none to prosperous and felt the loss of the money deeply.

He acted in a peculiar manner

Carney was a native of Ireland and was 45 years of age and lived with his wife and one daughter at their Walkerville home. Last spring Carney went to Ireland on a visit. About two months ago he returned and since that time had been acting in a peculiar manner.”

Carney’s body now lies at Duggan's undertaking establishment where an inquest will be held later this evening.

Then, seven years later, the family lost younger brother Hugh. Like his brother, Hugh died in the mine under mysterious – though not as violent – circumstances.

On the morning of January 9, 1909, the daily newspaper “The Butte Miner” reported the shocking death of my great uncle Hugh Carney:

Mystery Death of Hugh Carney

January 6, 1909

The Butte Miner

Little light shed on Carney

Hugh Carney met his death through falling from the mine cage between the 500 and 600 ft levels of the Bell Diamond, Mine on account of the gate becoming unfastened in some manner unknown to the jury”---was the verdict of the coroner's jury, at the inquest held at Walshe’s undertaking rooms over the death of Hugh Carney, a well-known miner who was killed on Wednesday.”

Verdict of Coroners Jury

The inquest on the body of Hugh Carney commenced yesterday morning but was not concluded until 5 0’clock last evening. The inquire was a most thorough one and every possible point which might in some way explain how the gate of the cage became unfastened was gone into, but no light was thrown on the question.

It was also told at the afternoon session that the door of the gate was found hanging on the wall plate between the 400 and 800ft levels. Deputy State Mine inspector William B, Oram, stated that he went through the shaft after the accident hoping to find anything to indicate how the cage gate had become unfastened. The verdict of the jury was to the effect that Carney came to his death by falling through the cage gate that became unfastened through some unknown means to the jury.

“The inquest lasted from 10 to 5 in the evening thirteen witnesses were examined and the testimony of all was so clear showing that Carne met his death through the fault of the company in not providing a secure gate on the cage.”

Hugh left a wife, Mary Francis, and eight children. In spite of the trying conditions of the weather, the funeral was well attended as Carney was well known and highly respected by the whole community. Hugh was 42 at the time of death, born in Edrim Glebe Killymard, Donegal, he had been amongst the early pioneers to the town. He had been working in the copper mines of Hancock County, Michigan, where he met his wife Mary Francis O’Sullivan, of West Cork parents.

A Butte mining song lamented such deaths:

Only a miner killed under the ground,

Only a miner and one more is found:

Killed by the company, no one will tell,

Your mining’s all over poor miner farewell

When the Mining Days Were Over

The demise of the Irish hold on Butte’s mining world gradually came about as a result of a slowdown in emigration from Ireland in the 1920s, old Irish miners retiring, and fewer miners sons taking up mining because of easier work elsewhere.

Mining finally ceased in the 1970s as mining corporations shifted their investments to South America. Butte now relies heavily on tourism, with an emphasis on its mining past.

And what became of my family? There are to this day still some Carney descendants in Butte, but the rest dispersed across the country as did countless other Irish emigrants in search of the American dream.

Hugh Carney’s children eventually settled in Seattle and California, as many Butte Irish did.

Great uncle John returned to Donegal just before the turn of the century with his West Cork-born wife, Margaret Sheehan, and their children, buying a farm at Ballydavitt. John died soon after in 1901 reputedly from miners’ consumption. A daughter, Kate, married into the Gallagher family of the Castle Bar, Donegal Town. John and Margaret’s surviving descendants Brian, and Eamonn, live in Mountcharles, Cape Cod, Mass., Spokane, WA. And Seattle, WA.

Catherine (Kate) Carney, my great aunt, had married Peter Lorretz in Brooklyn, and made the long trek to Butte in 1901. She became widowed in 1910. Kate spent her last days in California, with her teacher daughters, Mae and Kate, and son, John. Manus, along with Winnie, disappeared from Butte without trace. Annie Carney married Chicago-born John Crimmins in 1900. They had one daughter, Ann, and lived very Irish lives in Anaconda.

During my visit to Butte, I visited Hugh's grave but alas couldn't find any trace of Pat's burial, nor could I find the whereabouts of his wife and child. I've been searching for Pat's burial plot on and off since my visit.

Feadfaidh siad eile i Siochain.

May they rest in peace

---

Seán Carney was born into the Irish coal mining community of Maltby in South Yorkshire, UK. He worked in the construction industry for many years in the UK, Holland, Germany, Denmark, and Ireland. He first started writing in 1996 after visiting Butte, when he described the visit in a letter to an aunt in Donegal.

Since then he has written short stories and articles for the Donegal Times, Donegal Democrat, Irish Post, and The Harp.

In 2012, he published his first book, “The Forgotten Irish” which tells the history of the Irish mining community of Maltby. The book is still selling and can be ordered via Kennys Booksellers.

He has been married to Connemara girl Máire for almost 50 years. They have four children and live in Scarborough, North Yorkshire, where Seán founded the now-defunct but prestigious Scarborough Irish Festival in the 1980s.

*Originally published in September 2015

Comments