Editor’s note: On the anniversary of the Kingsmills Massacre, which took place in the early evening of January 5, 1976, a minibus full of workers from the Glenanne textile factory were shot dead on their way home in what is believed to have been an act of retaliation for the murder of two Republican families the night before. 10 Protestant men were killed; the only Catholic among them had been ordered to run away. One man, Alan Black, survived, despite being shot 18 times. In the wake of the attack, it was claimed by the South Armagh Republican Action Force, but former IRA leaders have come under pressure in the decades since to take responsibility. Some, including Black, have alleged state forces were somehow involved.

In 2016, Yvonne Watterson, originally from Northern Ireland and now living in Arizona, reflected on that murderous day:

It is January 5, 1976, at the end of a workday, and sixteen men are in a red minibus on their way home from the textile factory. Four of them get out at Whitecross, and the van continues on to Bessbrook. The craic turns to football and which team will make it to the top of the First Division, but it is tempered by what happened the day before when six local Catholics were murdered, ripping apart the Reavey and O’Dowd families.

Naturally, the men aren’t surprised when they spot the red lamp swinging up ahead near the Kingsmills crossroads. Increased security would be expected following yesterday’s murders. And this is South Armagh – “bandit country.”

What words work for what happens next? The men are ordered out of the van by gunmen who have been waiting for them in the hedges. Masked gunmen. This is not a British Army checkpoint. They are ordered to line up and put their hands on the roof of the van. They are asked to state their religion – Protestant or Catholic. There is only one Catholic among them, Richard Hughes, and when he is asked to identify himself, his Protestant workmates are terrified. In their dread, in their desire to protect him, they cover his hands with theirs, but he is identified and forced away.

It is this moment that is forever lodged in the corner of my heart that never left Northern Ireland. It is this moment – this split second of humanity – that Seamus Heaney recollects in his 1995 Nobel lecture:

“One of the most harrowing moments in the whole history of the harrowing of the heart in Northern Ireland came when a minibus full of workers being driven home one January evening in 1976 was held up by armed and masked men and the occupants of the van ordered at gunpoint to line up at the side of the road. Then one of the masked executioners said to them, 'Any Catholics among you, step out here'.

"As it happened, this particular group, with one exception, were all Protestants, so the presumption must have been that the masked men were Protestant paramilitaries about to carry out a tit-for-tat sectarian killing of the Catholic as the odd man out, the one who would have been presumed to be in sympathy with the IRA and all its actions.

"It was a terrible moment for him, caught between dread and witness, but he did make a motion to step forward. Then, the story goes, in that split second of decision, and in the relative cover of the winter evening darkness, he felt the hand of the Protestant worker next to him take his hand and squeeze it in a signal that said no, don’t move, we’ll not betray you, nobody need know what faith or party you belong to.

"All in vain, however, for the man stepped out of the line; but instead of finding a gun at his temple, he was thrown backward and away as the gunmen opened fire on those remaining in the line, for these were not Protestant terrorists, but members, presumably, of the Provisional IRA

"All in vain. In less than a minute, ten of the men are gunned down and left to die on the side of a road slippery with rain and blood. Tit-for-tat."

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

40 years later, the sole survivor, Alan Black, seeks no revenge. A survivor – and a witness – he is often stuck in those moments when, shot 18 times, he was left for dead. Every January, he finds himself going “into countdown mode — I look at the calendar and at the clock and think to myself ‘the boys have only five days or five hours or five minutes to live’, right up to the time of the ambush.” He seeks acknowledgment and justice for the boys and their families.

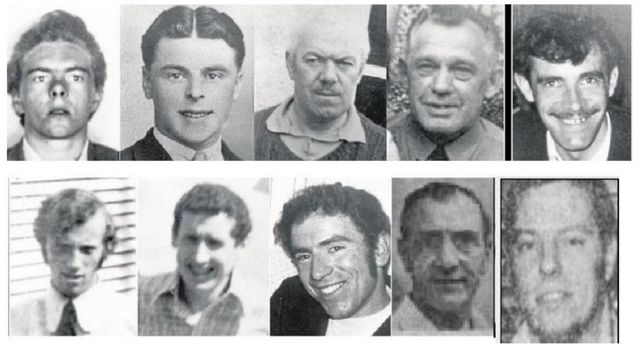

These men are known to me only through the tiniest details from a Belfast Telegraph article written in 2011: “Joseph Lemmon, whose wife was standing over their tea as he died; Reginald Chapman, a Sunday school teacher who played football for Newry Town; his younger brother Walter Chapman; Kenneth Worton, whose youngest daughter had not even started school; James McWhirter, who belonged to the local Orange lodge; Robert Chambers, still a teenager and living with his parents; James McConville, who was planning to train as a missionary; John Bryans, a widower who left two children orphaned; and Robert Freeburn, who was also a father of two. The van driver, Robert Walker, came from near Glenanne.”

The answers may never come, nor justice. What remains for us and what belongs to us, is the humanity on the side of a country road in South Armagh forty years ago. We would do well to hold on to it.

The birth of the future we desire is surely in the contraction which that terrified Catholic felt on the roadside when another hand gripped his hand, not in the gunfire that followed, so absolute and so desolate, if also so much a part of the music of what happens.

*Yvonne Watterson, originally from County Antrim, emigrated to the US in 1988 and settled in Arizona where she has enjoyed a highly successful career in public education. A graduate of Queen's University Belfast, Yvonne has been recognized for her work not only in school reform but also for her activism in immigration. Yvonne writes a bi-weekly column, "News Travels," for her hometown newspaper, The Antrim Guardian, contributes to IrishCentral, and runs her own website, Time to Consider the Lillies.

*Originally published in 2016. Updated in January 2025.

Comments