300 women participated in Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising.

Perhaps the best known is Countess Constance Markievicz, who fought for the duration in Stephen’s Green and who famously advised her fellow female fighters "Dress suitably in short skirts and strong boots, leave your jewels in the bank and buy a revolver."

Then there was Elizabeth O’Farrell, the nurse who delivered Padraig Pearse’s note to surrender to the British forces, whose story has much deservedly been resurrected in the past few years.

But there are many more extraordinary stories of women who bravely aided and fought in the Rising. From gunrunners to frontline fighters to those charged with rebuilding in the wake of the rebellion, here are a few of their profiles in courage.

On the front lines

The role of women in front-line combat is one that's been historically overlooked. Relegated to providers of medical aid and other kinds of support, it's only fairly recently that stories of some pretty incredible women are getting the credit they've long been due. Armed and prepared to die for what they believed in, women like Margaret Skinnider, Winifred Carney and Kathleen Clarke were prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice to see Ireland free.

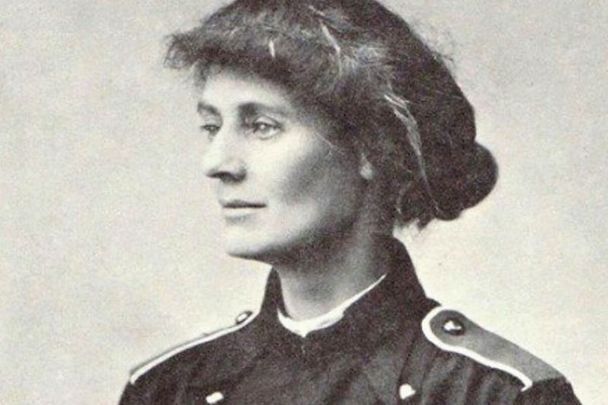

Margaret Skinnider

A Scottish schoolteacher, Margaret Skinnider left her home for Dublin with the intention of joining the fight for Irish freedom. She ended up staying with Countess Markievicz – as did many rebels who had no other place to stay in the city – and would write one of the most telling passages about the horrible conditions she saw in the poorest sections of Dublin.

She wrote, “I do not believe there is a worse street in the world than Ash Street. It lies in a hollow where sewage and refuse falls; it is not paved and is full of holes. One might think that it had been under shell fire. The fallen houses look like corpses, the others like cripples leaning upon crutches. These houses are symbolic of the downfall of Ireland. They were built by rich Irishmen for their homes. Today they are tenements for the poorest Irish people – the poor among the ruins of grandeur.”

Skinnider was recruited first to infiltrate the Beggar's Bush barracks and to collect valuable reconnaissance for those who would later be tasked with destroying it. Even though she didn't know why the recon was needed at the time, she proved to be so good at what she did that she was taken to meet James Connolly and was trusted not only with acting as an escort to members of his family but to collect, transport and distribute explosives.

Handling explosives was something she'd done before – she'd made the trip from Scotland to Dublin with some in her hat, staying on the deck of her ferry and away from any heat or electricity that might accidentally detonate them.

Standing directly behind Padraig Pearse, Elizabeth O'Farrell.

During the Easter Rising, she was based out of St. Stephen's Green and tasked with being a bicycle messenger and scout – which meant that she spent much of the time dodging bullets. By Tuesday, she traded being in the cross-hairs of sniper fire for a rifle of her own and set up on the roof of the College of Surgeons to act as the Rising's own sniper – quite successfully. That still wasn't enough, and by the next day, she was an integral part in planning and executing the bombing of Shelbourne Hotel, along with the bombing of houses along Harcourt Street to cut off British access routes to the College.

Skinnider was shot three times during the attempt and spent the next three days in the College and under heavy fire. Eventually returning to Scotland for a short time she, like many others, ultimately ended up heading to America to gain support for the Irish.

Her fight was far from over on another front, too, and when she applied for a pension in 1925, she was denied despite her well-documented military service. It was argued that military service made her a soldier, and only men could be soldiers, so she wasn't eligible. After a legal battle finally ended with her receiving her pension in 1938, it only started to change the way that the role of women in the Rising would be remembered.

Winifred Carney

Originally born in County Down, Winifred Carney and her family moved to Belfast when she was little and still a child. She was still living in Belfast years later when James Connolly requested she head to Dublin to join the Easter Rising. She did – armed with two of the most dangerous tools of the trade: her typewriter and a revolver.

Carney was no stranger to the fight for Irish freedom, with the area of Belfast the family settled in long known for its history of rioting and conflict. The Catholic Carney met Connolly in 1912 when he was based out of Belfast and working with the Textile Workers Union (and offered her a secretarial post). She became close friends with his daughter and with his family, and not long after she joined the Citizens Army she became his confidante and personal secretary.

Given the moniker 'The Typist with the Webley', Carney was stationed alongside Connolly in his Easter Rising headquarters at the General Post Office. In charge of writing up orders and dispatches, she would record his last orders after his wounding, and be arrested along with the others sent to Kilmainham. She would spend eight months in jail, but her story certainly didn't end there.

Remaining active in political circles, in union debates, and as an anti-treaty protester, Carney was working with the Northern Ireland Labor Party in 1924. There she met – and eventually married – one of the most unlikely men. George McBride was a Protestant and a former soldier for the British, and their marriage meant that they were both abandoned by the people they had fought alongside – on both sides. Outcasts from their respective social circles, they ended up moving to Belfast, joining up with the socialist movement, and remaining happily married until Carney's death 15 years later. Carney was buried in Milltown Cemetery, and because of her marriage, her family refused to put a marker on her grave. One was finally erected by the National Graves Association.

Kathleen Clarke

Born in Limerick in 1878, Kathleen Daly became Kathleen Clarke when she married Nationalist Thomas Clarke, not long after he had been released from prison for his insurgent activities. After spending some time in New York they returned to Dublin in 1907 to join the front lines of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). The Clarkes set up a tobacconist shop, which became a front for IRB meetings and for the planning of the Easter Rising. In 1914, she was one of a dozen founding members of Cumann na mBan, and within only a handful of months, their numbers had risen into the hundreds. Disagreements on whether or not to follow through with the plans for the Easter Rising split the organization (and the Irish Volunteers) with Clarke and her husband firmly on the side of a rebellion.

From the start, contingency plans were put in place should the Easter Rising fail – and Kathleen Clarke was an integral part of those back-up plans. Should the IRB fall, it was going to be up to her to rebuild – and she did. Her brother and husband were both among those arrested and ultimately executed for their part in the Rising, and afterward, Kathleen joined forces with Michael Collins to reestablish the IRB and become one of the driving forces behind Sinn Fein.

With the secrecy of the utmost importance, there were only a handful of people entrusted with all the information that would be needed to rebuild should all the leaders of the IRB be captured, killed or executed – she was one such person. Because of the information she had, she wasn't allowed to take part in the fighting but was still arrested because of her connections with the IRB. Visiting her husband one last time in jail before his execution, she didn't tell him that she was pregnant – she would tragically lose the baby not long after.

But Clarke had been tasked with rebuilding, and by 1917 she was a member of Sinn Fein's Executive Committee. She would also establish the Irish Volunteers' Dependents' Fund, which provided financial support to the widows and children left behind after the Easter Rising.

Clarke was also behind the tricolor ribbon campaign; while World War I saw many people wearing Union Jack ribbons, she created a surge of Irish pride with the replacement of the British flag on the jackets of the people.

The women who armed the nation and changed history

There's no doubt that the events of Easter Week in 1916 changed Irish history forever. Soldiers and civilians alike picked up their weapons as men, women, and children showed that they were willing to give their lives for Irish freedom. One of the biggest challenges wasn't just finding people willing to fight, but arming them – and that task fell to a handful of people who were risking their lives before the first shot was even fired.

Helena Molony

By the time of the Easter Rising, Helena Molony was already a well-known actress who took her politics to the stage. A part of the Abbey Theatre, she was an incredibly outspoken proponent of Nationalist ideals, putting them on the stage where she could reach countless people. Stuck in France at the beginning of World War I, and her involvement with the Abbey Theatre earned her another gig – helping with the organization of the theater troop into a military division of the Irish Citizen Army, all at the request of James Connolly.

Her work in the theater meant that she was pretty much expected to travel all across Europe, and when it came to weapons smuggling, that was a huge bonus. In the first days of 1916, the rebels were concentrating on arming their men (and women). Molony was instrumental in that, even being sent to London on a trip to requisition some firearms. Those guns were simply carried in her suitcase, which they hoped wouldn't be searched by British officials who would have no reason to suspect a theater actress was a gun runner. Not only was she not searched, but a polite British Army recruit was kind enough to carry her bags to the ferry for her.

The days leading up to the Rising were filled with cooking and other prep work, but when the time came, Molony donned a rather smart tweed outfit (likely from a theater costume department), then grabbed a gun and joined the group that stormed Dublin Castle. The assault failed – because of nothing more than a split-second hesitation, which she would later say was the instant that the armed volunteers truly realized what they were in the middle of doing – but Molony and her contingent retreated to City Hall, which she soon left to run for reinforcements. When she returned their commander, Sean Connolly, was killed by sniper fire, and the group remained under fire throughout the night. As British troops advanced on the tenuous stronghold, and the mostly unarmed group surrendered, the prisoners were dealt with amidst the assumption that the women were only present as nurses and medical support, not as the front-line combatants that they were. Ultimately, they were eventually transferred to Kilmainham.

Released in December of 1916, Molony continued to travel, recruit, and continue to be targeted by those who didn't agree with her. A part of the Trades and Labour Council into the 1960s, she remained a stalwart campaigner for trade unions and the rights of workers, and for the equal treatment of women in the new Ireland.

Molly Osgood

The events of Easter week, 1916 would change Irish history forever, but not all monumental events happened in those few days. The fight for Irish freedom had started months earlier, and without the crew of the Asgard, the rebels would have had only a relative handful of guns to arm themselves with.

The ship was designed by one of Europe's finest naval architects, and it was commissioned as a wedding gift for the daughter of Boston physician (and developer of rabies antibodies) Dr. Hamilton Osgood. Molly Osgood was marrying a somewhat eccentric writer – and nationalist – named Erskine Childers. Childers, son of an English father and an Irish mother was English-educated and fought in the Boer Wars, years that shaped his opinion of British imperialism forever afterward.

His young wife, Molly, (who walked with two canes after a childhood incident left her with broken hips), shared his love of the sea. They settled in London but spent considerable time on the ocean, throwing their support in with the Irish Volunteers by 1913 – ten years after Erskine became a household name with the release of his spy thriller “The Riddle of the Sands” and after he toured southern Ireland. That tour saw him come to the realization that some of the same problems he'd already seen with British colonialism were happening in Ireland, too – and something needed to be done.

By 1914, they were at the head of a small group that was financing the purchase of 1,500 Mauser rifles and 49,000 rounds of ammunition from the German-based company Moritz Magnus der Jungere, to be delivered into the hands of the rebels that would make their mark on history that Easter week.

The British government had been on the lookout for just such a shipment, knowing that it was bound to come in response to the 35,000 rifles that had just been moved into Ulster. The Childers spread the rumor that guns were going to be moved into Ireland on fishing trawlers, and while the British scrambled to intercept these innocent ships, the Childers set out from the Welsh coast. Their crew included Mary Spring Rice and another ship, Kelpie, with Conor O'Brien and sister Kitty manning the helm.

Nine days after they disembarked, they met up with the German tug Gladiator, well into Belgian waters. There were so many crates that it took five hours to transfer the cargo, and dodging storms on the way back, Kelpie and Asgard docked at Howth Harbour soon after – where hundreds of members of the Irish Volunteers were waiting, including founder Michael O'Rahilly. Phone lines and communications had already been severed, lookouts were scattered throughout the area in strategic locations, and the guns were passed into the hands of the rebels.

When news of the landing and the distribution of guns reached British ears, police were dispatched. As the newly armed volunteers disappeared, civilians threw rotten fruit at the police force – who opened fire in a skirmish that became known as the Bachelor's Walk Massacre. All told, the trip to arm the Volunteers had taken about three weeks, and was detailed by Mary Spring Rice in logs and diaries that describe the perilous journey from start to finish.

Erskine Childers would ultimately suffer much the same fate as many of the leaders of the Easter Rising, but not for several years. In 1922, he was arrested and charged over the possession of a gun, which had been given to him by Michael Collins. Even though he was offered a reprieve if he re-thought where his loyalties lay, he refused and was executed on November 24, 1922.

H/T Stories from 1916, RichmondBarracks.ie, Easter1916.ie, RTE

*Originally from Attica, New York, Debra Kelly is a freelance writer and journalist who has seen most of the US during her travels. Ready for something new, she's now living in the wild hills of Connemara with her husband and plenty of animals. She is a frequent contributor to Urban Ghosts, Listverse, and Knowledgenuts.

*Originally published in 2016, updated in April 2025.

Comments