The story of how the Irish came to Milwaukee is a quintessentially American tale of immigration, hardship, community, and adventure.

The first trickle of immigrants from Ireland to Milwaukee arrived in the 1830s. At this time, Wisconsin was not yet a state but a vast territory almost devoid of white settlement. Today we think of the state as being part of the ‘Midwest’ but then there was thought to be nothing ‘middling’ about its geography: it was a part of the West, plain and simple.

To make the journey to Milwaukee and set up home there required true pioneer spirit and the hardy handful of Irish who were among the city’s first inhabitants were flushed with a sense of adventure.

In the early years, Milwaukee was dominated by Germans; they were the city’s preeminent group but by the end of the 1840s growing number of Irishmen and women had begun to settle in the city.

The reason was not hard to pinpoint. The Great Famine that began in 1845 left a scar on the Irish soul that will never heal. A million died and a further million and a half fled - the vast majority going to America.

Chased across the Atlantic by sharks that tailed the coffin ships looking for an easy meal, the result was that by 1848 some 15% of the population of Milwaukee was Irish.

Few when stepping aboard a ship bound for the New World would have told their fellow travelers they intended to strike out west. Most made a go it at first back east and the average arrival had already spent seven years in America before they decided to hitch their wagon west.

For those that did, a few common trends emerged. First of all, the land was cheaper the further you got from the east coast and after centuries of landlords, many Irish found the prospect of buying a patch of land to call their own an irresistible pull.

For others, it was simply a sense of adventure. They had come this far, seen so much, why not push on even further?

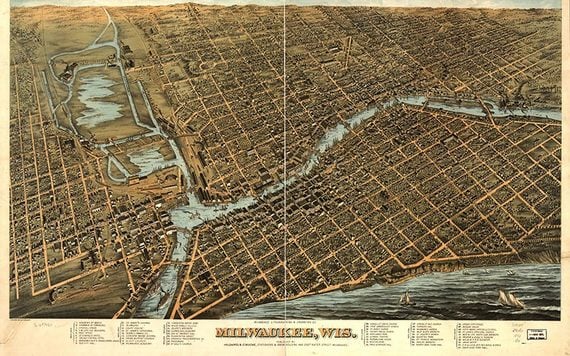

Milwaukee in 1872.

One Mrs. Greaney persuaded her husband and his brother to move west because she, “could always see bright things in the distance.”

Three brothers from the Burren in Co. Clare - an area particularly badly hit by the Famine - had thought to settle in Illinois but after they were told there was a fever in the state they decided to press on to Wisconsin which an old man had told them had “the best drinking water in the world!”

Often, all it took was for one Irishman to end up in Milwaukee and dozens more of his friends would follow.

For their part, the Territorial Government was eager to encourage more immigration and placed adverts in all the major Irish newspapers back east urging readers to make the trip west.

It took, “An entrepreneurial spirit and a willingness to take chances [for people] to make the trek westward”, the historian David Holmes concluded and the result was a city of hardy Irish folk, keen to work hard and willing to make a success of their new city.

The building of railroads saw a flood of Irishmen race west to help in the construction and after the tracks were laid and the last paycheck cashed hundreds decided they wouldn’t leave but settle down in Wisconsin.

As with everywhere in America, sectarianism against the Irish was rife and one of the great attractions of Milwaukee was that many of their new German neighbors were Catholic, too.

Nevertheless, it took several generations before the two would seamlessly blend together and most Irish lived strictly amongst their fellow countrymen and women.

Most settled in Downtown Milwaukee and the area soon garnered something of a reputation as an Irish “ghetto”.

Others preferred to set up home in the more rural areas that surrounded the city and it was here, isolated from German or Anglo-Saxon influences, that the Irish culture took root deepest of all.

One William Shea, a native speaker of the Irish language, recalled asking two teenage girls for directions to his Uncle Joe’s in broken English shortly after arriving in Wisconsin.

“When I asked them the way to Uncle Joe’s, they started making fun of me, and I told them in Irish they could kiss my ass and one girl answered back in Irish and said, ‘I don’t have to.’”.

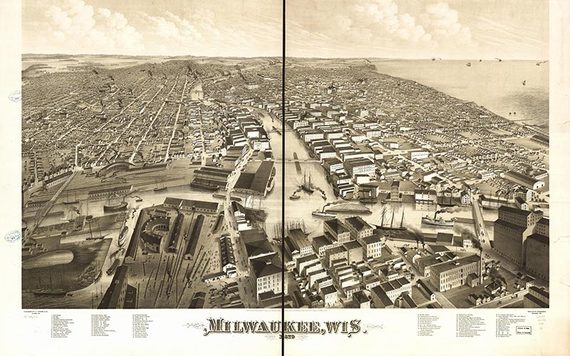

ilwaukee in 1879.

As they put down roots, so the Irish became into politics and, although the Milwaukee Irish never grew into as strong a faction as the Irish in New York in Massachusetts, they did exert a certain influence over the politics of their state.

Most Irish became strong supporters of the Democratic Party - the Republicans were regarded suspiciously as a Protestant party and the Democrats hailed as the champions of immigrants.

In 1852, the state legislature’s Irish caucus succeeded in passing a motion condemning Britain for their imprisonment of Thomas Francis Meagher and his associates following the Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848.

Tragically in 1860, just as the community was beginning to flex its political muscles, many of its best and the brightest were snatched away.

One night in September the PS Lady Elgin left Chicago where many passengers had been to hear Lincoln’s opponent, Stephen A. Douglas, give a campaign speech.

But the ship was soon being buffeted by gale force winds and crashed into a small schooner. Within 20 minutes the ship had sunk below the wild waves of Lake Michigan, taking 300 souls with it.

The vast majority of the dead were Irish and every single Irish family was said to have lost a relative. Due to the political nature of the trip, a great number were involved in politics and historians have since speculated that the loss of so much talent permanently transferred the balance of power to Milwaukee’s German community.

The community did go on to provide the city with its longest-ever serving mayor, Daniel Hoan. Mayor Hoan was elected in 1916 and served 24 years back to back in office. A staunch socialist, he is credited with launching the city’s system of public buses after the death of a friend at the dangerous driver.

But few would argue that the Wisconsin Irish ever wielded the same power or clout as their relatives to the east.

As the last of the city’s first generation immigrants died off after the First World War, so too did the community’s collective political cohesion. The Irish in Milwaukee were just as likely to vote for the Republican candidate as their neighbors and many proudly cast their votes for the most hated man ever spawned by Irish America: Senator Joseph McCarthy.

McCarthy grew up in eastern Wisconsin where few of other Irish had settled and his mostly Dutch Catholic neighbors dubbed his home, “the Irish settlement".

In the 1950s, there was still a general suspicion amongst Protestant Americans that Catholics’ primary loyalty was to the Pope and not the United States. Historians have debated whether McCarthy’s rabid anti-communism was an attempt to prove his loyalty to the country he loved.

And many of his Irish American constituents flocked to his banner of hatred with enthusiasm.

“Everyone knows,” one letter wrote to an Irish paper opined, “the great job Senator Joseph McCarthy is doing in fighting communist infiltration in America. Only recently the Bishop of Cork, after a visit to America, revealed the courageous fight McCarthy has made against communism. It is the duty of the Catholic… not to sit idle, or remain indifferent to this attack on a fellow Irishman and Catholic of whom we are proud.”

If Irish Wisconsinites were key to the rise of one famous Republican, 60 years later they received a mixture of ire and praise for helping elected Donald Trump as President. The state had been regarded as part of Hillary’s “blue firewall” but the hemorrhaging of the Catholic vote saw the Badger State turn a surprising shade of red on election night.

Today, only 6.5% of Milwaukee’s population claims Irish heritage (rising to 11% across the state of Wisconsin) but they’re an influential few percent without a doubt.

Comments