Founded by WB Yeats and Lady Gregory while Ireland remained occupied by the British, the importance of the Abbey in Ireland's history cannot be overstated.

“Growing up in Donegal, I’d never been to the Abbey Theatre, but my late mother, Margaret, had always hoped that I would perform there.”

So says seasoned performer Ruth McGill. After uprooting to Dublin and having seen Fiona Shaw play the titular character in Medea, the then 18-year-old was determined that one day she too would grace Ireland’s national stage. Her first production was The Cherry Orchard and, since then, Ruth has been a regular fixture there, receiving rave reviews for her nuanced performances.

“When you enter the stage door on the first day of rehearsals, an energy envelopes you - a reminder of the Abbey’s history and the ideals it was built upon,” Ruth reveals. “It feels like you’re walking on sacred ground.”

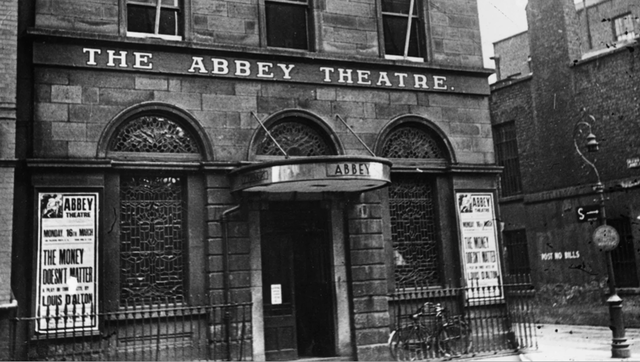

This history cannot be overstated. The Abbey Theatre was founded in 1904 when Ireland remained occupied by the British Empire. Its arrival was linked to the growing Gaelic Revival Movement, which had previously yielded Conradh na Gaeilge (Gaelic League) and the Gaelic Athletic Association.

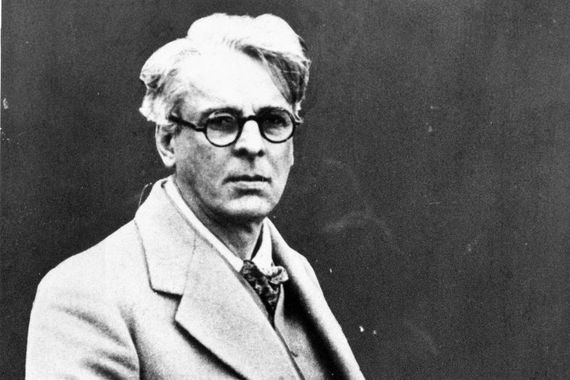

Spearheaded by poet W.B. Yeats and writer Lady Gregory, the theatre was located on Abbey Street and Malborough Street in central Dublin. Purchased by an English theatre patron Annie Horniman and designed by Joseph Holloway, it comprised of two separate buildings - a bank and city morgue, fitting considering the founders wanted to sound the death knell on the then-popular melodrama and buffoonery theatre and, instead, breathe life into Ireland’s ancient idealism.

W.B. Yeats.

While the Abbey wasn’t Dublin’s first theatre, it was undoubtedly the first of its kind to produce plays that were written by Irish playwrights and performed by Irish actors.

“Before this, to be successful, Irish playwrights including Oscar Wilde, G.B. Shaw and Dion Bouccicault had to write for English audiences,” says Caitlin White, a PhD candidate in public history who also runs excellent tours in Dublin. “The Abbey wanted to produce plays about Irish nationalism, identity and freedom.”

She added: “At the time, many believed they belonged to an ancient Gaelic race, separate from the British, and were agitating for political independence.”

An example of a play fitting this early manifesto was Cathleen Ní Houlihan, co-written by Yeats and Lady Gregory. It proved so popular that people were being turned away by the third night.

In the play, Cathleen initially appears as a haggard, old woman and arrives in a house revealing that her four green fields - an allegory for Ulster, Connacht, Munster and Leinster - have been taken away from her. Enraptured, the men fight her cause. Their sacrifice transforms Cathleen into a young, beautiful queen.

“Cathleen is an old allegorical name for Ireland,” Caitlin tells me. “It’s such a thinly veiled, political play - it’s wild to think that they staged this while Ireland was apart of the British Empire, and people paid to see it and it wasn’t broken up!”

The Playboy riots

Another pivotal moment in the Abbey’s youth was The Playboy Riots in 1907, where audiences disrupted performances of J.M. Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World.

The Abbey Theatre, Dublin.

The play tells the story of Christie Mahon, whose claims of slaughtering his tyrannical father impresses locals in a rural shebeen - notably Pegeen Mike, the fortnightly barmaid.

“One of the reasons the audiences rioted was because of the representation of Irish women,” Caitlin explains. “Another was because nationalists felt Synge was presenting a barbaric image of Irishhood to the world. How could a nation full of Pegeen Mikes and Christies, who glorify the savage killing of a father, be able to govern themselves?”

Synge’s intention, however, was to bring realism and naturalism to the Irish stage - a style that was then becoming increasingly popular thanks to the likes of Norwegian playwright Henry Ibsen.

“Synge wanted to show life as it was, not as it was perceived to be,” Caitlin says.

In the red

From on-stage death to off-stage debt, drama ensued in 1910 when benefactor Annie Horniman severed ties with the Abbey because they wouldn’t close the theatre following King Edward VII’s death.

“While she was great friends with Yeats, Horniman didn’t necessarily agree on the theatre’s nationalistic outlook. When they refused to close as a mark of respect, she withdrew her support immediately.”

The theatre struggled financially afterward, so, in the decade that followed, they toured America extensively - a profitable endeavor as many Irish emigrants in the States retained nationalist sympathies. However, it was far from incident-free.

In 1912, The Playboy of the Western World’s cast was arrested in Philadelphia for performing “immoral or indecent” plays. The case was ultimately dismissed.

The 1916 Rising

In addition to being its inaugural production in 1904, the Abbey scheduled Cathleen Ní Houlihan for Easter Monday in 1916. In a case of life imitating art, many of the actors due on stage were actually playing out the themes of blood sacrifices on Dublin’s streets - one, Seán Connolly, died.

The streets of Dublin in the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising.

“Because of the strong connection between the founding of the Abbey and the promotion of Gaelic identity, it’s no surprise that so many of these actors, employees, producers and playwrights became involved in the violent struggle for independence,” says Caitlin, noting the plaque in the theatre that commemorates these heroes.

One of many lesser-known examples of the courageous role that the Abbey played in shaping Ireland’s national history in the early 20th century relates to larger-than-life actor and socialist Helena Molony.

During the 1913 Lockout - a long-lasting industrial dispute between 20,000 workers and 300 employers - Helena dressed Jim Larkin, a Labour Party founder and wanted man, in costumes and wigs from the Abbey. This elderly woman's disguise helped him evade the police’s attention, allowing him to address the masses from a balcony on O’Connell Street’s Metropole Hotel.

Three years later, Helena was entrusted with the printing press used to produce the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

“At the time, you had to register your printing press because you could be printing seditious material,” Caitlin reports. “Liberty Hall, then the headquarters of the Irish Citizen Army, was beside the Abbey. When there were tip-offs about raids, Helena would rescue it and hide it under the Abbey stage.

“The night before the 1916 Rising, they stayed up all night printing the proclamation and Helena slept on the many copies, safeguarding them.”

The Plough and the Stars

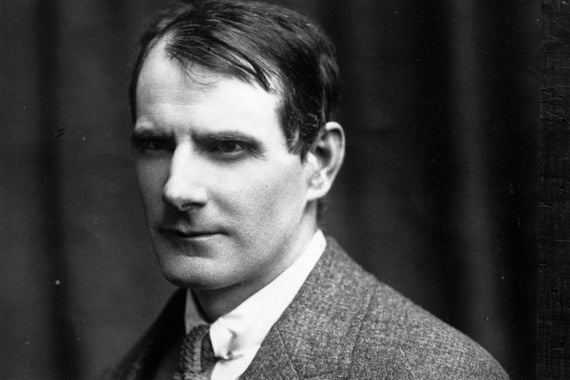

Additional theatrics succeeded the 1926 premiere of Seán O’Casey’s seminal The Plough and the Stars - a sober and realistic depiction of the Rising. Even though the Abbey retained its nationalistic character some 22 years following its genesis, the institution was, first and foremost, a theatre that strived to highlight the truth of people’s lives.

Sean O'Casey.

“O’Casey didn’t glorify the Rising. He didn’t make heroes of those who participated in it - he showed them as real people,” Caitlin insists.

“But at this point, in this nation-building, post-colonial era, that wasn’t supposed to be mentioned. The Rising was nothing but good; no one suffered. It didn’t impact negatively on people’s lives - anything other than that couldn’t be said in the public sphere, which is why the riots followed.”

The first State-funded theatre

Another boast, worthy of a curtain call, arrived that same year when the Abbey became the English-speaking world’s first state-funded theatre, saving them from financial ruin.

“The Abbey doesn’t belong to anyone,” Caitlin proudly mentions, “the Abbey belongs to Ireland - that’s what makes it different to other theatres. Whatever role you’re working in, you’re only a gatekeeper for the next person.”

A year later, in 1927, the Abbey welcomed a second theatrical space, the Peacock, which also enjoys the distinction of being the stage where I made my professional acting debut, in 2004, in Finders Keepers, written by Peter Sheridan!

Over the decades, the Peacock has earned a reputation for experimental and Irish-language productions. The famous ballerina, Ninette de Valois, even ran a ballet school there during the mid-20th century.

Phoenix from the ashes

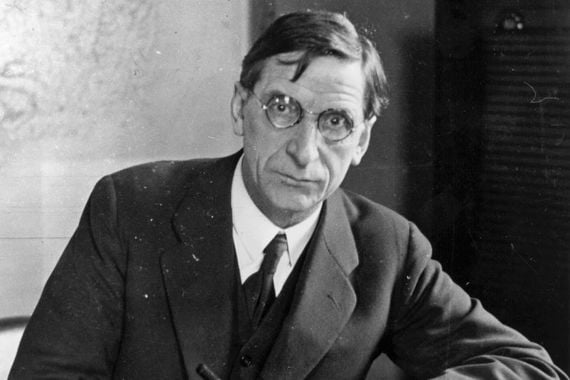

In 1951, disaster struck when a backstage fire engulfed the entire premises. After a 15-year stint in the Queen’s Theatre on Pearse Street, President Eamon de Valera opened the new Abbey Theatre, in 1966, which coincided with the 50th anniversary of the Rising. Joining him were the surviving Abbey employees who had participated in the events of 1916.

President Eamonn de Valera.

Dublin architect, Stephen Wall, tells me: “The concept by Michael Scott - who also designed Bus Áras nearby - was very modern. He wanted the building’s drama to be on stage, so the theatre itself - a box of sorts - was extremely plain from the outside. But once you enter, this magical stage reveals itself.”

Stephen adds: “What that meant, in reality, was that it was quite a dull building with plain brick façades and minimal architectural detailing, which is why I don’t think the public warmed to its external appearance.”

In 1991, McCullough Mulvin designed the entrance portico, which extends to the bar on the first floor - this addition, according to Stephen, “enlivens the front façade and gives the theatre a proper entrance.”

In 2007, the auditorium’s seating was re-jigged, based on the principles of a more democratic space.

“Yes, there are seats that have different prices, but there is no physical marker to distinguish them,” Caitlin reports. “It’s reflective of a wider societal shift in a democratic, egalitarian society.”

Caitlin also mentions that, in the foyer today, there is an ornate, Celtic-design mirror from the original building, saved by locals during the 1951 fire. Unfortunately, its companion piece mysteriously disappeared that night.

Artists take flight

In the new premises, the Abbey continued to act as a springboard for renowned or up-and-coming playwrights, including Brian Friel, Tom Murphy, Hugh Leonard, Frank McGuinness, and a personal favorite, Marina Carr. Celebrated actors such as Siobhán McKenna, Brendan Gleeson, Stephen Rea, John Mahoney, and Ruth Negga have performed across the duo of stages.

In addition to a promise to promote female voices, recent initiatives at the Abbey have included free previews and inexpensive front seats.

“In the last 20 years, these changes have helped to bring in a new demographic that you wouldn’t normally associate with the Abbey,” Caitlin praises. “And when you have a more diverse audience, you have a more diverse programme.”

Curtain falls

Of course, the Abbey’s progress was hampered in 2020 by the unwelcome arrival of the pandemic.

“COVID shut us down two nights before our official closing date,” says Limerick actor Patrick Ryan who was performing in The Fall of the Second Republic at the time. “We were given a couple of hours’ notice to clear out the dressing rooms - it was very swift how the country shut.”

Despite the abrupt curtain call, Patrick says it was a great feeling to perform in the Abbey - “every Irish actor has a desire to play there.”

The Abbey recently announced the exciting appointments of Caitríona McLaughlin as its new Artistic Director and Mark O’Brien as its new Executive Director.

According to Mark: “As we emerge from the current worldwide crisis, we have the exciting opportunity to take stock, listen and recalibrate - allowing us to develop processes, structures and spaces where people are supported to flourish and create great work in a trusting, creative environment.”

Despite risings, fires and pandemics, it seems the show will always go on at the Abbey Theatre.”

* This article was originally published in May 2021 and updated in Nov 2024.

Comments