African Americans traveled from the US to Ireland on behalf of anti-slavery groups in the 1800s

February marks the observance of Black History Month, a national celebration in the US honoring African Americans and recognizing their contributions to the history of the United States. In the 1800s, many traveled across the Atlantic on behalf of various American anti-slavery organizations.

Read More: When Frederick Douglass met Ireland's "Liberator" Daniel O’Connell in 1845

Ireland was a safe haven for black abolitionist lecturers, both fugitive slaves and free-born persons, who journeyed transatlantically in order to highlight the evils of slavery and to plead the case for the anti-slavery movement with a goal to secure an Irish alliance.

For more than three decades, African-Americans who traveled to various parts of Ireland on their lecture tours found receptive audiences for their anti-slavery discourses as they were treated with tolerance and respect and experienced the freedom and equality denied to them in America.

These transatlantic campaigners, a few of which are highlighted below, were credited with creating “deep interest in the anti-slavery cause…many [in Ireland] who never thought on the subject at all, are now convinced that it is a sin to neglect.”

In 1823, when Daniel O’Connell, the Kerry native referred to as the “Liberator” for his efforts on behalf of Catholic Emancipation and human rights, expanded his portfolio to include abolition, he condemned American slavery as anathema to the fundamental principles upon which the country was established:

"Of all men living, an American citizen, who is the owner of slaves, is the most despicable; he is a political hypocrite of the very worst description. The friends of humanity and liberty, in Europe, should join in one universal cry of shame on the American slaveholders! ‘Base wretches,’ should we shout in chorus – base wretches, how dare you profane the temple of national freedom…"

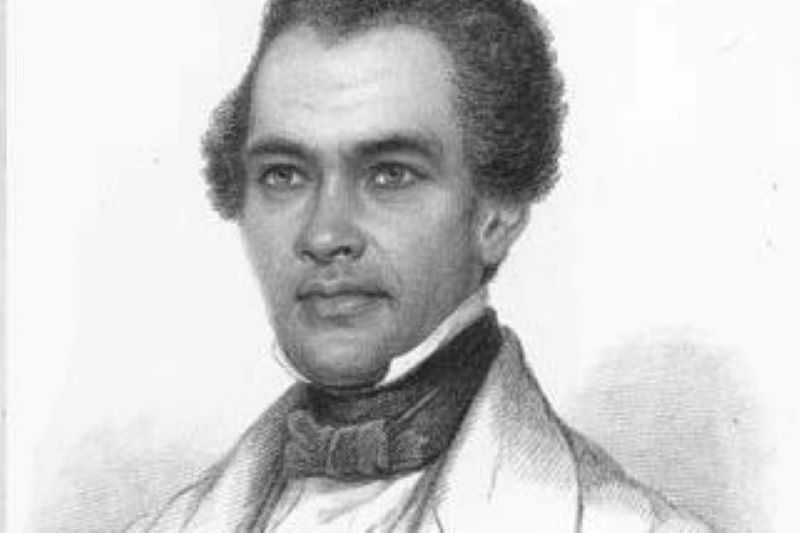

Charles Lenox Remond

Charles Lenox Remond (Samuel Broadbent / Boston Public Library)

O’Connell’s stirring words reverberated across the Atlantic, beckoning Charles Lenox Remond, the first black lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society, to visit Ireland. The son of affluent merchants and staunch abolitionists, and the grandson of a veteran of the Continental Army who served during the American Revolution, Lenox Remond was free-born in Massachusetts. For a black man in antebellum America, his free-status and distinguished lineage, rooted in the founding of the nation, was distinctive.

In a speech in Dublin, Lenox Remond acknowledged Ireland’s own long-standing pursuit of freedom from oppression, saying, “I stand here to advocate a cause, which, above all others, be, and ever has been, dear to the Irish heart – the cause of liberty.”

When Lenox Remond returned to America, he carried with him a petition signed by O’Connell and 60,000 Irishmen urging immigrants in America to join the movement. The document, entitled “Address of the Irish People to Their Countrymen and Countrywomen in America” and known as the Irish Address, made a plea to Ireland’s exiles to “unite with the abolitionists…until perfect liberty be granted to…the black man as well as the white man.”

Read More: Galway to honor Virginia slave who died in Ireland, America's first sports star

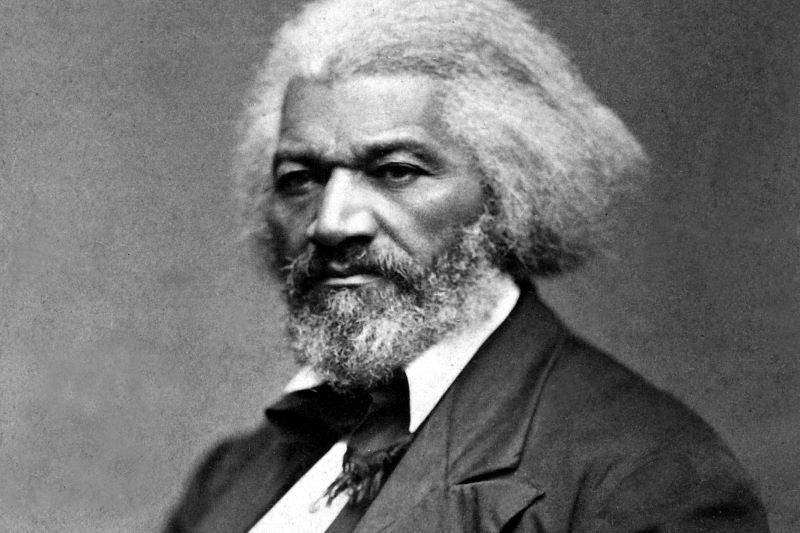

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (Public Domain)

In 1845, 27-year-old Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave from Maryland, traveled throughout Ireland, delivering forty, well-attended, lectures in Dublin, Limerick, Belfast, Wexford, and Waterford. Douglass’ masterful oration skills, combined with his unfaltering commitment to freedom and equality, induced the “Liberator” to laud Douglass as the “black O’Connell.”

Richard Davis Webb, a Dublin printer and founding member of the Hibernian Anti-Slavery Society, published an Irish edition of Douglass’ autobiography. The initial run of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, American Slave sold out quickly.

The second run contained significant additions – a preface and an appendix. These modifications enabled Douglass to articulate the political and social changes he envisioned for America, thus making the Irish edition a noteworthy publication in the canon of his works.

The Irish people’s acceptance of Douglass, evident by their “crowded to suffocation” attendance at his lectures and treatment of him as an equal, although a fugitive slave, had a profound effect on him. He acknowledged to a friend: “I seem to have undergone a transformation.” In a letter to William Lloyd Garrison, a prominent American abolitionist, Douglass explained the basis for this metamorphosis:

"One of the most pleasing features of my visit, thus far, has been a total absence of all manifestations of prejudice against me, on account of my color. The change of circumstances, in this, is particularly striking. . . . I find myself not treated as a color, but as a man – not as a thing, but as a child of the common Father of us all."

Read More: How an Irish book tour transformed Frederick Douglass

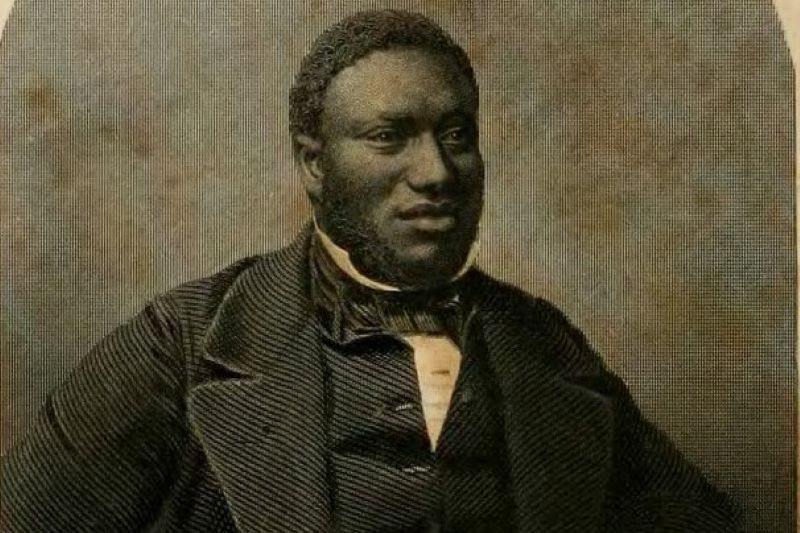

William Wells Brown

William Wells Brown (Public Domain)

William Wells Brown, an escaped Kentucky-born slave and abolitionist lecturer, was on a tour in Europe when the Fugitive Slave Act was enacted in the U.S. The act required all escaped slaves, once captured, to be returned to their owners. Due to Brown’s increased risk of apprehension because of his public profile, he chose to remain abroad for an extended period.

Brown’s travels to Ireland, England and France are recounted in his book, Three Years in Europe: or Places I Have Seen and People I Have Met. In reference to his visit to Dublin in 1849, Brown unequivocally expressed his opinion of the Irish people:

"The Irish are indeed a strange people. How varied their aspect, how contradictory their character! Ireland, the land of genius and degradation, of great resources and unparalleled poverty, noble deeds and the most revolting crimes, the land of distinguished poets, splendid orators, and the bravest of soldiers, the land of ignorance and beggary!”

Samuel Ringgold Ward

Samuel Ringgold Ward (Public n)

Similarly, Samuel Ringgold Ward, an abolitionist born into slavery in Maryland, journeyed to Ireland in 1854 as an agent of the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada. A chapter in Ward’s Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro describes his travels in Ireland, highlighting visits to Dublin, Belfast, Sligo, Mullingar, Limerick, Cork, Cobh, and Mallow.

When visiting Killarney, a tourism destination dating to the 1740s, Ward was struck by the magnificence of the landscape and the friendliness of the people, writing:

"The rich romantic scenery, the beauty of the lakes, the fine old ruins of Mucruss [sic] Abbey and Ross Castle, the beautiful grounds…the affability of the company we met, all gave us a variety of most pleasing sights and sounds; and, being favoured with extraordinarily fine weather, we could but be gratified with our short sojourn in that picturesque locality."

Read More: Ireland's has only one pro-slavery Confederate memorial - is it next to fall?

Sarah Parker Remond

Sarah Parker Remond (Public Domain)

Lecture tours were not limited to men. Sarah Parker Remond, a younger sister of Charles Lenox Remond, visited in 1859 on behalf of the American Anti-Slavery Society. Like her brother, she was free-born and had endured cruel acts of discrimination because of “an unpopular complexion.”

By embarking on a transatlantic voyage to serve the cause of abolition, Parker Remond also hoped that she “might for a time enjoy freedom.”

After addressing the Dublin Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, Parker Remond spent a month traveling to Waterford, Clonmel and Cork meeting with local societies. Parker Remond used her femininity to expose the horrific miseries endured by female slaves in order to establish an emotional bond of sympathy with the Irish women in her audiences.

Though the subject matter of her talks was intensely sensitive, accolades were bestowed on the speaker for possessing convincing presentation skills, “in all she said, there was something so persuasive.” Parker Remond transcended the gender barrier at a time when it was uncharacteristic for any woman, particularly an exotic “lady of colour,” to make a public presentation.

In honor of Black History month, the following powerful words, spoken by Parker Remond in Dublin, may serve as a tribute to the African-American champions of freedom who visited Ireland:

“The lives of good men [and women] are not lost when they die for justice sake; for so great is justice that she rewards all who suffer for her with greatness....the just cause for which they rendered up their lives gives them immortality, and their spirits walk the earth.”

Black Irish Identities: The complex relationship between Irish and African Americans

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments