From the late eighteenth century, the small island of Ireland played a major role in both the movement to end the slave trade and the movement to end enslavement wherever it existed.

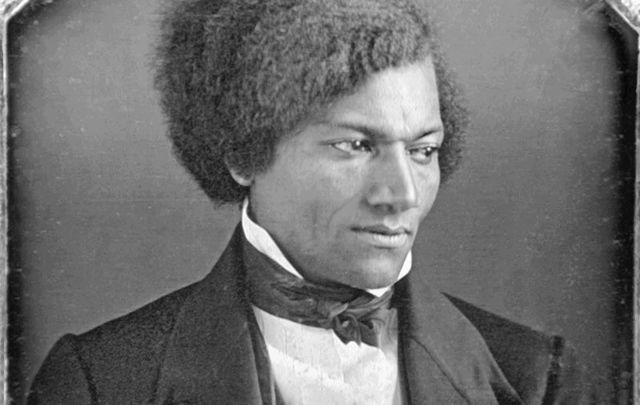

Early activists included members of the United Irishmen who hosted the visit by African-born Olaudah Equiano in 1791. Equiano was the first of almost 30 black abolitionists—both men and women—who lectured in Ireland in the decades prior to the American Civil War. The most well-known of these visitors was Frederick Douglass, who admitted that one of the reasons he remained in Dublin for a month was in the hope of meeting his hero, Daniel O’Connell. Their meeting changed his life.

The historic meeting between the 27-year-old American and the 70-year-old Irishman took place in Dublin on September 29, 1845. The American had been born into hereditary enslavement but had self-emancipated seven years earlier. By the laws of his country, however, he was designated a ‘fugitive slave’. The Irishman had been born a second-class subject in his own country. During their long and eventful lives, both men would overcome prejudice and overturn legal obstacles to fight for the civil rights of all people regardless of their colour, gender, ethnicity or religion. Almost 200 years later, they continue to be remembered as champions of peaceful political action that can lead to positive change.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Douglass had fled from America only one month earlier as he was in danger of being captured and returned to enslavement following the publication of his best-selling Narrative or life story. On his journey across the Atlantic, he had been denied access to a cabin because of his color. Following his arrival in the port of Liverpool, Douglass traveled onwards to Dublin where Richard Webb, a Quaker publisher and ardent abolitionist, had offered to print an Irish edition of his Narrative. Douglass came to Ireland intending to stay for four days, but the warmth of the welcome meant that he remained for four months. During this time, he gave almost 50 lectures and his Narrative proved to be so popular that a second Irish edition was published.

Even before arriving in Dublin, Douglass was aware of Ireland’s tumultuous history and the long search for religious equality and political independence. While still enslaved, he had read speeches by Irish nationalists, including several by members of the United Irishmen and by O’Connell. He was impressed not only with their patriotism but by the fact that they placed their own struggles in a wider demand for international human rights. He would later acknowledge that during his stay in Ireland he had come to realize that it was not enough to be a single-issue abolitionist—oppression had to be fought wherever, and in whatever form, it existed, he wrote, ‘I confess I should be ashamed to lift up my voice against American slavery, but that I know the cause of humanity is one the world over’.

A pivotal moment in this transformation came when he attended a Repeal meeting in Conciliation Hall in Dublin in order to hear O’Connell speak. As was usual, part of the ‘Liberator’s’ speech was spent denouncing slavery in America. Douglass was transfixed. He admitted to being ‘completely captivated’ by hearing the Irishman speak: ‘His power over an audience is perfect’. When O’Connell was made aware of Douglass’s presence, he invited him to join him on stage and to address the meeting. Although Douglass was self-educated—it was illegal to teach slaves to read or write— the young exile proved that he was a match for the elder statesman in his ability to mesmerize an audience. Paying tribute to O’Connell’s achievements, Douglass told the audience that change would only come if people were willing to ‘Agitate, agitate, agitate!’

Douglass returned to America in April 1847, his freedom having been ‘purchased’ by women abolitionists. He devoted the remainder of his life to fighting not only for the end of enslavement but also for equality for all. Like O’Connell and many other Irish abolitionists, he was frustrated by the failure of many Irish Americans to oppose slavery, which culminated in the disgraceful Draft/Race Riots in New York in 1863.

The two men did not meet again but, until his death in 1895, Douglass would refer to his time in Ireland and to O’Connell as the inspiration for his own political development. In 1889, then an elder stateman himself, Douglass was appointed Consul General to Haiti—the first black republic in the world. Haiti’s economy (once the richest island in the world) had been bankrupted by being forced to pay reparations to France for daring to seek their independence. For Douglass, the comparison was obvious, he told an audience in 1893:

It was once said by the great Daniel O’Connell, that the history of Ireland might be traced, like a wounded man through a crowd, by the blood. The same may be said of the history of Haiti as a free state …

Douglass died in 1895, aged 77. That very day, he had attended a meeting for women’s rights, where he had received a standing ovation.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

To honor the historic meeting of these two humanitarians in 1845—one then reaching the end of his remarkable career, the other on the path to becoming an international champion of human rights – the African American Irish Diaspora Network is hosting a Diaspora Leadership Award Gala in New York on 29 September 2022. Those being honored include President Mary McAleese. This event will also be a time to reflect on what we, as individuals, and as descendants of two great diasporas, can do to effect positive change in the world.

For more information on the Gala, contact Carla at: [email protected] or click here.

Professor Christine Kinealy is a Board Member of the African American Irish Diaspora Network. She is the author of "Frederick Douglass and Ireland. In His Own Words" (2018) and "Black Abolitionists in Ireland" (2020). For more information, click here.

Comments