The key facts to help you understand Ireland's 1916 Easter Rising

Editor's Note: Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising." This passage is taken from his book “Irish Miscellany: Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Ireland.” This chapter is entitled “Can’t tell the rebels without a scorecard?”

In Ireland there will always be a throwaway reference to some (failed) moment in Irish history: “Sure Pearse and the lads didn’t have a chance in the GPO, did they?”

You can admit your ignorance, nod your head with false sagacity, or know that “Pearse and the lads” in question were involved in the Easter Rising of 1916, where they were brutally crushed by the British forces.

Read more

So here are some historical figures and moments that every (or would-be) Irishman (or woman) should have in their rebel vocabulary:

The Patriots of the 1916 Easter Rising

Theobald Wolfe Tone, Lord Edward Fitzgerald, Robert Emmet: this group of “modern” Irish revolutionaries were from the landed Protestant gentry and were members of the United Irishmen who fought the British with only pikes in the Uprising of 1798.

They were annihilated by British infantry at the Battle of Vinegar Hill in Wexford, a moment in Irish history eerily brought to life by Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney. In his haunting poem “Requiem for the Croppies” he recalls how the rebels of 1798—the “croppies” because of their short, cropped hair—moved swiftly in rebellion:

“The pockets of our greatcoats full of barley...

No kitchens on the run, no striking camp...

We moved quick and sudden in our own country.”

In defeat they were forgotten until their graves were marked when:

“…in August... the barley grew up out of our grave.”

The sacrifice of the United Irishmen was to inspire Irish patriots for nearly two hundred years:

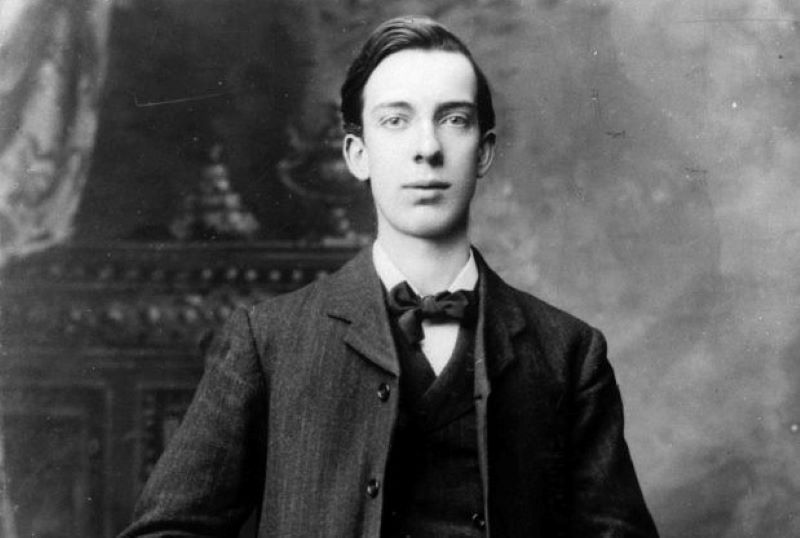

Padraig Pearse: The “President” of Irish Republic, the existence of which he declared on the steps of the General Post Office (GPO) on Easter Monday 1916. Under his command, the occupying rebels held out for nearly a week before surrendering. He was executed on May 3, 1916, by firing squad at Kilmainham Gaol.

Padraig Pearse (US Library of Congress)

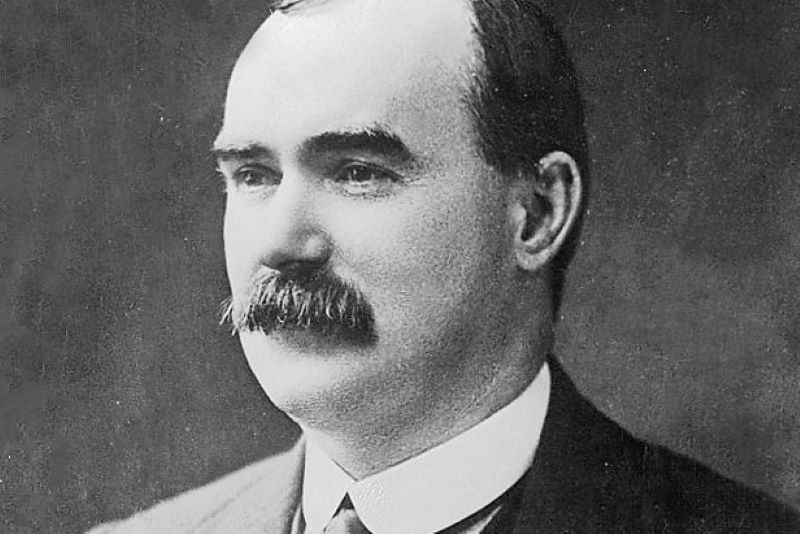

James Connolly: Irish socialist labor leader, founder and commandant general of the Irish Citizen Army who was severely wounded in the leg in the GPO. His injuries were so severe that the British shot him in a chair at Kilmainham on May 12, 1916.

James Connolly (Public Domain)

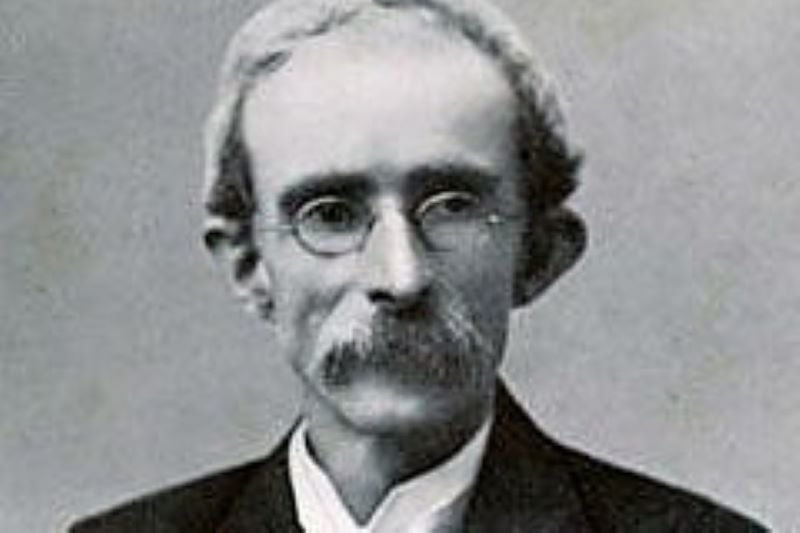

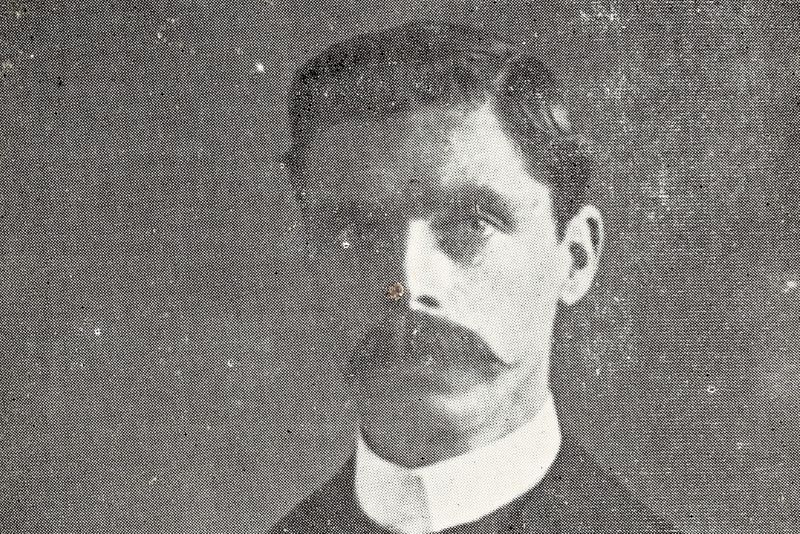

Thomas Clarke: The cagey old Fenian and the real force behind the Easter Rising. His nurturing of such young rebels as Seán MacDiarmada, Joseph Mary Plunkett and Pearse would change the course of Irish history. Naturalized in Brooklyn while in exile, he was the only American citizen to be executed by the British, as a result of the skirmish, on May 3, 1916.

Thomas Clarke (Public Domain)

Countess Constance Markievicz: Co-commander of St. Stephen’s Green in 1916 and the first woman to ever hold a cabinet ministry. Read more about Markievicz in Chapter 7, “Ferocious Fenian Women.”

Countess Constance Markiewicz (Public Domain)

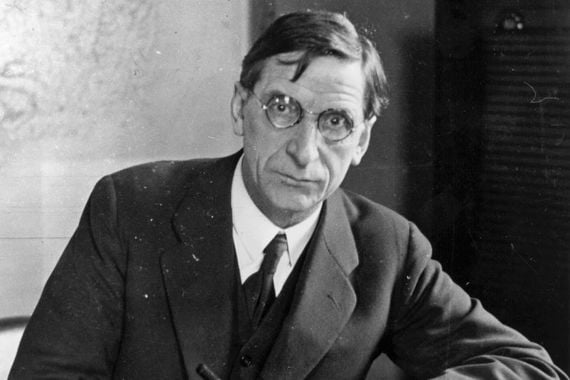

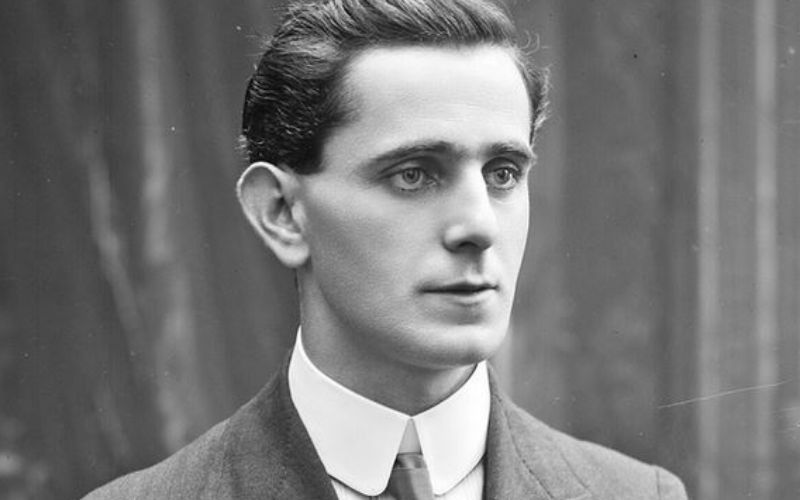

Éamon de Valera: The senior commandant of the Easter Rising who was not shot because of his natural-born American citizenship. He would be for the next fifty years either Taoiseach (prime minister) or President of the Republic of Ireland. He died in 1973 at the age of 92.

Eamon de Valera (Getty Images)

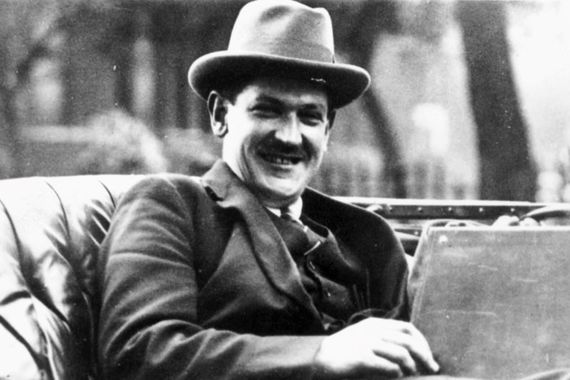

Michael Collins: The legendary IRA leader and the father of the modern Irish state. During de Valera’s absence in America during the War of Independence, he systematically created an intelligence network that targeted British agents and spies. On the morning of November 21, 1920, his personal assassination squad eliminated most of the British Secret Service in Dublin.

Just over twelve months later he signed the Treaty that created what is today the Republic of Ireland. He died in an ambush on August 22, 1922, at the age of 31.

Michael Collins (Getty Images)

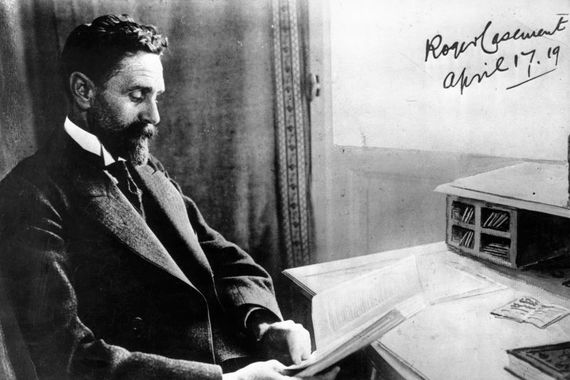

Sir Roger Casement: The last of the sixteen rebels executed for their participation in the Easter Rising. Casement’s job during the Rising was to land rifles in County Kerry, which turned into an outright disaster. Captured by the British he was brought to London to stand trial.

During the trial, his notorious “Black Diaries” were leaked to suppress calls for his exoneration by such notables as George Bernard Shaw and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The diaries—still controversial to this day—allegedly revealed Casement’s homosexual romps on two continents.

He was hanged by the British on August 3, 1916, in Pentonville Prison in London. W.B. Yeats wrote a poem about him with the haunting refrain: “The ghost of Roger Casement/Is beating on the door.”

Sir Roger Casement (Getty Images)

Kevin Barry: An 18-year-old medical student and IRA volunteer, Barry was captured in northside Dublin in an ambush that went awry in October 1920. Despite cries for mercy, he was hanged in Mountjoy Prison on November 1, 1920, All Saints Day. One of Ireland’s most popular rebel songs was written in his honor:

“Another martyr for old Ireland,

Another murder for the crown,

Whose brutal laws may kill the Irish,

But can't keep their spirit down.

Lads like Barry are no cowards.

From the foe they will not fly.

Lads like Barry will free Ireland,

For her sake they'll live and die.”

24

24

Kevin Barry (Public Domain)

Kevin Barry (Public Domain)

The 1916 Executions

The frenzy to execute the leaders of the Easter Rising began on May 3 and continued until May 12.

“I am going to ensure,” said General Sir John Grenfell Maxwell, general officer commanding-in-chief of the British forces in Ireland, “that there will be no treason whispered for 100 years.” Ignorantly, he began the process that would drive Britain out of most of Ireland for the first time in 700 years.

W.B. Yeats in his poem, “Easter 1916” remembered the sacrifice of those who rose up and were executed for their efforts:

“I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.”

Besides the aforementioned Pearse, Clarke, Connolly, and Casement, the honor roll of martyrs executed by the British in May 1916 include:

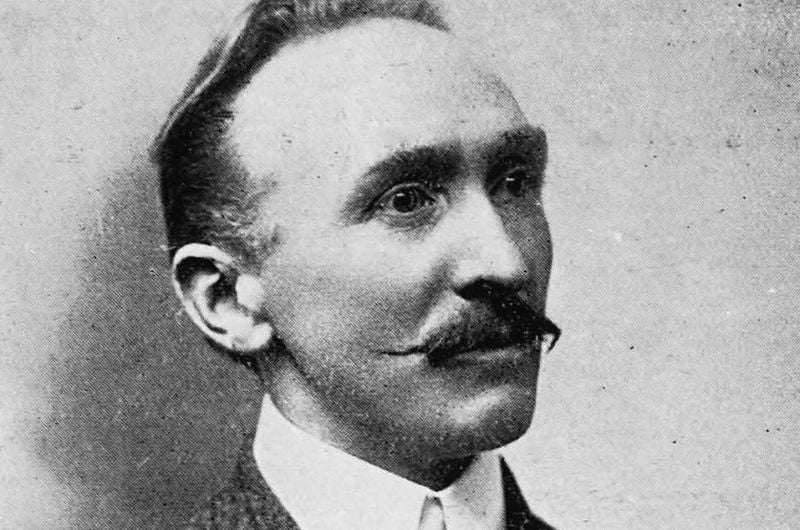

Thomas MacDonagh: Poet, author, school teacher, he was the commandant in charge of Jacobs Biscuit Factory, another skirmish location. He was a close friend and associate of Pádraig Pearse and taught at Pearse’s school, St. Enda’s in Rathfarnham. He was married to Muriel Gifford, Grace Gifford’s sister. Executed by firing squad, Kilmainham Gaol, May 3, 1916.

Thomas MacDonagh (Public Domain)

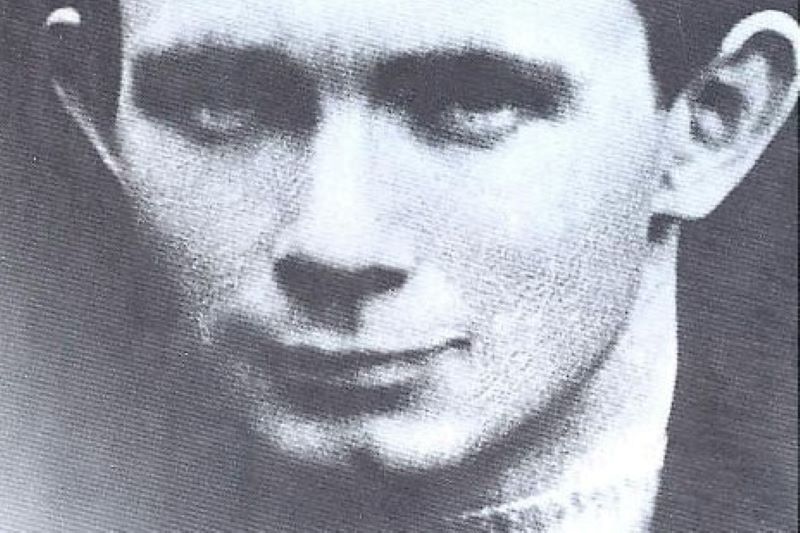

Joseph Mary Plunkett: One of the most mysterious leaders, he served as the movement’s foreign minister, traveling to Germany trying to drum up support for the coming insurrection. At the time of the Rising, he was dying of tuberculosis of the neck glands. Michael Collins was his personal bodyguard and aide-de-camp.

Hours before his execution he married his fiancée, Grace Gifford, in the Catholic chapel at Kilmainham. Immediately after the wedding he was taken out and shot on the morning of May 4, 1916. (See more on Grace Gifford Plunkett in Chapter 7, “Ferocious Fenian Women.”)

Joseph Mary Plunkett (Public Domain)

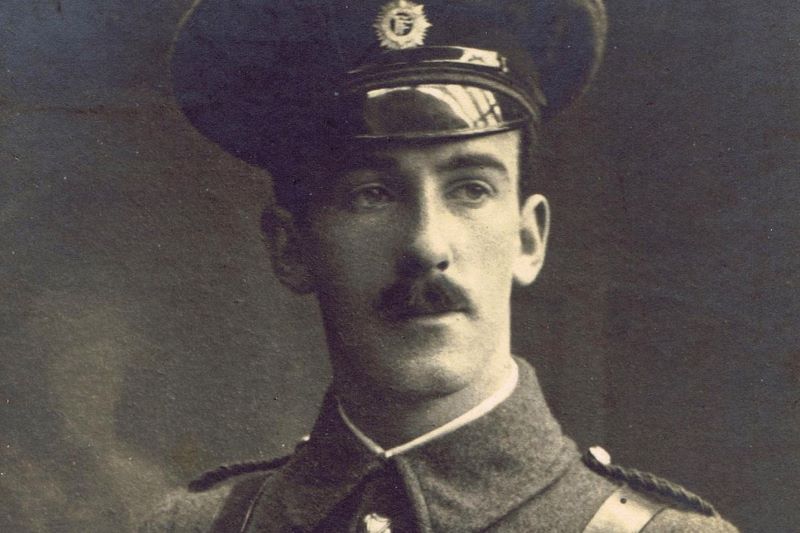

Edward (Ned) Daly: Commandant of the Four Courts. A member of the fiercely Fenian Daly family of Limerick. Brother of Kathleen Clarke and brother-in-law of Tom Clarke. Executed at Kilmainham, May 4, 1916.

Edward (Ned) Daly (Public Domain)

Michael O’Hanrahan: Vice commandant to Thomas McDonagh at Jacobs. Executed at Kilmainham on May 4, 1916.

Michael O’Hanrahan (Public Domain)

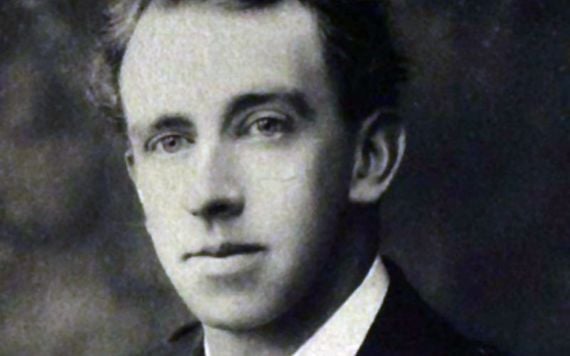

William (Willie) Pearse: The younger brother of Pádraig Pearse, which was the main reason he was executed. Although he held the rank of captain in the Irish Volunteers, he was not part of the senior leadership. He was a talented sculptor and his work can be viewed at the Pearse Museum in Rathfarnham, St. Andrew’s Church, Westland Row, and St. Stephen’s Green. Executed at Kilmainham on May 4, 1916

William Willie Pearse (Public Domain)

John (Seán) MacBride: Was on his way to his brother’s wedding reception when he ran into the revolution and decided to take part, fighting at Jacobs. Husband of Maud Gonne and father of Seán MacBride, who would go on to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1974. His hatred of the British led him to go as far as South Africa to fight against them in the Boer War. Although he was a romantic rival for Maud Gonne with William Butler Yeats, Yeats remembered him in “Easter 1916” as “A drunken, vainglorious lout…Yet I number him in the song.”

John (Seán) MacBride (Public Domain)

Éamonn Ceannt: Co-founder of the Irish Volunteers, he commanded the South Dublin Union during the Rising. Executed at Kilmainham on Mary 8, 1916.

Éamonn Ceannt (Public Domain)

Con Colbert: Commanded the rebels at the Marrowbone Lane distillery, not far from the Guinness Brewery. Executed at Kilmainham on May 8, 1916.

Con Colbert (Public Domain)

Seán Heuston: A railroad worker, Heuston commanded the Mendicity Institute on the Liffey, holding off the British for several days. The nearby Heuston Railroad Station, where Seán worked, is named in his honor. Executed at Kilmainham on May 8, 1916.

Seán Heuston (Public Domain)

Michael Mallin: chief of staff of Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army, he commanded, along with the Countess Markievicz, St. Stephen’s Green and the College of Surgeons during the Rising. Executed at Kilmainham on May 8, 1916.

Michael Mallin (Public Domain)

Thomas Kent: along with Roger Casement, he was the only rebel not to be executed at Kilmainham. Executed at Cork Detention Barracks on May 9, 1916.

Thomas Kent (Public Domain)

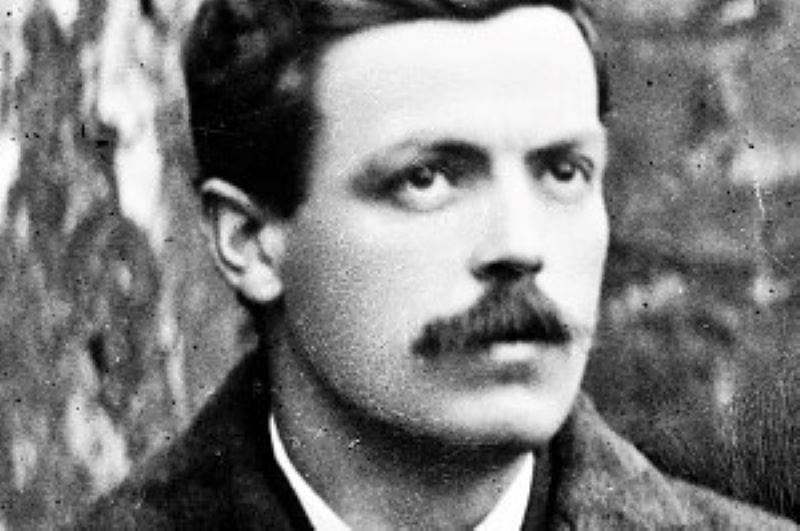

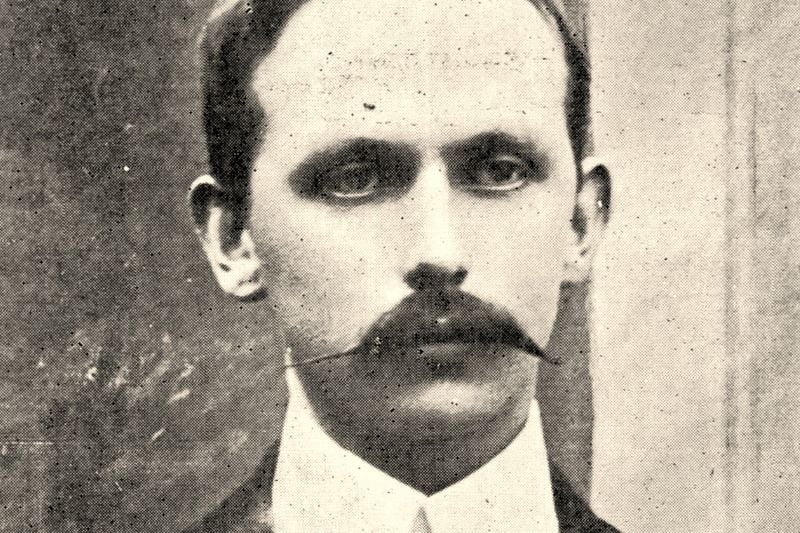

Seán MacDiarmada (John McDermott): Next to Tom Clarke, he may have been the most influential man behind the Rising. He was a master organizer and people were drawn to the movement because of his charismatic character. A former Belfast barman, he was stricken with polio in 1912. Executed at Kilmainham on May 12, 1916.

Seán MacDiarmada (Public Domain)

Yeats remembered the executed rebels in his poem, “Sixteen Dead Men”:

“O but we talked at large before

The sixteen men were shot,

But who can talk of give and take,

What should be and what not

While those dead men are loitering there

To stir the boiling pot?”

The Events

The War of Independence: the name given to the struggle for Irish independence during the years 1916-1921.

GPO: The General Post Office, O’Connell Street, Dublin, where the Easter Uprising began on Monday, April 24, 1916. It is the most important building in Irish history and is still functioning as an active post office.

GPO (Ireland's Content Pool)

Kilmainham Gaol: This 18th-century prison fortress is located on the south side of Dublin. In the weeks following the Easter Rising fourteen leaders were executed here by firing squad. There is a riveting, albeit disturbing, tour of the prison and the breaker’s yard where the rebels were executed and should be on every tourist’s must-do list.

Kilmainham Gaol (iStock)

Glasnevin Cemetery: Located on the north side of Dublin minutes from the City Centre, this is the final resting place of many a famous Irishman from Parnell to Brendan Behan. It is, however, the place where most of Ireland’s revolutionaries are planted, including Michael Collins and Éamon de Valera. You can visit the grave of Sir Roger Casement and Kevin Barry and visit the appropriately named Republican Plot where the likes of Cathal Brugha, Harry Boland, John Devoy, and Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa are interred. It was at Rossa’s grave in August 1915 that Patrick Pearse made his famous speech, proclaiming, “The fools, the fools, the fools, they have left us our Fenian dead.”

IRB versus IRA: everyone knows what the Irish Republican Army (IRA) is, but many are confused about what the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) was. The IRB was formed in 1859 in New York City by John O’Mahony and its members were known as “Fenians,” because they were followers of the ancient Celtic warrior, Finn. It was a highly secretive organization, dedicated to freeing Ireland from British rule by force. Many of its members participated in the Rising of ’67 and spent time in prison. (They also invaded Canada twice from the U.S.) In the 1880s another branch called “The Invincibles” terrorized the British both in Ireland and England. Almost all the hierarchy of the Easter Rising were members of the IRB and its last head was Michael Collins. It effectively died with Collins in 1922.

Bloody Sunday: There are three “Bloody Sundays” in modern Irish history. The first one occurred in 1913 when police charged striking workers in O’Connell Street; the second in 1920 when Michael Collins’s agents assassinated fourteen agents of the British Secret Service in Dublin and the British retaliated by firing into the crowd at a football match in Croke Park, killing another fourteen; the last occurred in 1972 when the British army, unprovoked, murdered fourteen civil rights protesters in Derry.

Michael Collins in Croke Park the day of Bloody Sunday in 1920 (Getty Images)

The Treaty: The Treaty is the name given to the piece of paper Michael Collins signed on December 6, 1921, creating the Irish Free State, which eventually evolved into the Republic of Ireland in 1949.

Civil War: the conflict between pro- (Collins) and anti- (de Valera) Treaty forces in 1922-23. It left scars that have only disappeared in the last few years.

Béal na mBláth: The area of County Cork where Michael Collins was gunned down. In Irish, it means “the mouth or the gap of the flowers.” Brendan Behan’s mother, Kathleen, always called Collins her “laughing boy” and Behan wrote his most famous poem:

“The Laughing Boy,” about Collins’s death:

“It was on an August morning, all in the morning hours,

I went to take the warming air all in the month of flowers,

And there I saw a maiden and heard her mournful cry,

Oh, what will mend my broken heart, I've lost my Laughing Boy.”

The Twelve Apostles: the nickname given to Michael Collins’s personal assassination Squad, famous for shooting most of the British Secret Service in Dublin on Bloody Sunday 1920. Members included:

Vinny Byrne, who started out in Jacob’s Biscuit Factory in 1916 at the age of 15 and by 1922 was a commandant-colonel in the Free State Army. Vinny was an extremely active member of the Squad and responsible for the slayings on Bloody Sunday at 38 Upper Mount Street. In old age he described for a joint BBC/RTE history of Ireland what happened that day: “I put the two of them up against the wall. May the Lord have mercy on your souls. I plugged the two of them.”

Mick O’Donnell and Paddy Daly were two of the leaders of the Squad. Daly, from Parnell Street, went on to be a general under Michael Collins during the Irish Civil War.

Charlie Dalton wrote a wonderful reminiscence of the War of Independence called With the Dublin Brigade, in which he describes the utter terror he experienced on Bloody Sunday.

The scope of the Bloody Sunday operation was so huge that the members of the Squad could not handle it by themselves. So members of the Dublin brigade were brought in to supplement them. One of these members was Seán Lemass, who shot British agents in Baggot Street. Lemass went on to serve in de Valera’s cabinet and was responsible for the establishment of both Aer Lingus and Ardmore Studios before he became Taoiseach in 1959. He was the first Taoiseach to travel to the North, trying to find common ground between the two governments of Ireland. He has, perhaps, the greatest quote about his short time in the Squad: “Firing squads don’t have reunions!”

--

Dermot McEvoy was born in Dublin in 1950 and immigrated to New York City four years later. He is a graduate of Hunter College and has worked in the publishing industry for his whole career. He is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising," "Terrible Angel," "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," and "The Little Green Book of Irish Wisdom." He lives in Greenwich Village, New York.

Comments