For over a century she was vilified as the woman whose actions burnt down the Windy City, left 300 dead and 100,000 homeless.

Catherine O’Leary was an Irish immigrant who was born some time in the 1820’s. Until the fateful events of the night of October 8, 1871 her life had passed without note and without the events of that night it’s likely not even her descendants would remember her today.

Chicago at that time was still a new city. Founded a mere 30 years earlier, it was reckoned to be the fastest growing city in the entire world. Most of it had been constructed in haste – and poorly at that – almost everything was made of wood and tightly packed together.

The summer of 1871 had been a scorcher and with winter approaching most of the city’s barns were packed with fuel and animal feed. Strong winds were rattling through the city and at around 9pm Daniel “Pegleg” Sullivan spotted flames dancing up and down the O’Leary family’s barn.

It took 20 minutes for fire engines to arrive and by then the flames had already engulfed the street and the strong winds were fanning the blaze towards the city's center at an alarming speed.

As the Great Fire spread the wind whipped it into a “fire whirl,” which is best described as a tornado of flames. The hopes of helpless residents that the Chicago River would act as a firebreak were cruelly dashed when the oil on the polluted waterway helped the flames to cross unhindered to the north side.

Prisoners were sprung from the local jail and the mayor sent pleading messages to nearby towns, begging them for urgent help.

Valiantly, the city’s firefighters continued to battle the gluttonous fire, but it was not until the evening of the 9th that the wildfire began to die down.

But it was days before the burning cinders had cooled to ashes and only then could local officials begin to survey the damage. In total, the fire had ripped through an area of the city four miles long and three quarters of a mile deep, leaving only scorched black ashes in its wake. An estimated $222 million ($4 billion) worth of property had been destroyed.

But the heartbreak and the damage were never going to deflect intrigue – even temporarily – as to who started the fire, and no sooner had panicked Chicagoans been raised from their beds did rumors begin to swirl about the origin of the blaze. It was not long before the finger of blame was pointed at Catherine O’Leary.

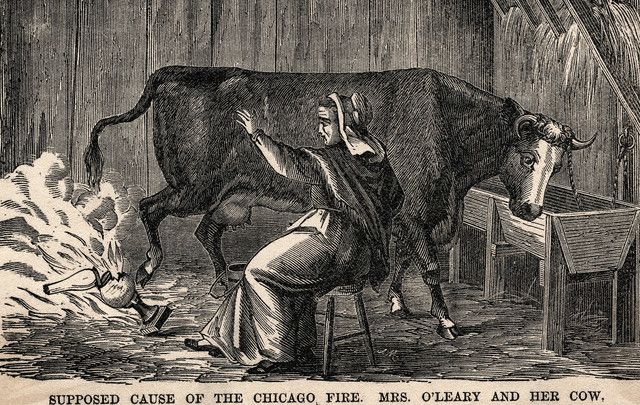

O’Leary, it was alleged, had been milking her cow in the barn when the animal had kicked over a lantern, engulfing the building in flames. Despite the distraught woman’s protests that she had been in bed the whole time, the rumor was believed by many and the event was famously depicted in cartoons.

O’Leary was in many ways the perfect scapegoat: she was poor and Irish – a much maligned social group at that time. So ingrained was anti-Irish prejudice at the time that many newspapers even reported that she had been passed out drunk when her barn caught fire.

Other theories are that “Pegleg” Sullivan caused the blaze himself and blamed the O’Learys to avoid the finger of suspicion being pointed at himself. In later years a local journalist admitted that the story had been fabricated and in 1942 a wealthy local business man confessed on his deathbed that the fire had broken out when he and a few teenage friends had been playing cards in the O’Leary barn.

O’Leary died – “heartbroken” and unexonerated” – in 1895 but her descendants never gave up the fight to clear her name.

126 years after the Great Fire of Chicago a number of O’Leary’s relatives – watched by curious journalists – gathered before the city’s Committee on Police and Fire to hear her officially cleared of all guilt.

Testifying alongside historians, her great-great-granddaughter Nancy Knight Connolly put across the family’s version of events that night. The panel concluded that actions of “Pegleg” Sullivan should have been further examined.

"We always knew that she was innocent," a thrilled Nancy Knight Connolly enthused afterwards. "But everybody else thought they did it. So now we'll be exonerated."

It was a case of justice delayed but ultimately not denied.

Comments