Early in the morning of 6 December 1921, the "Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland" – better known as the Anglo-Irish Treaty – were signed in London by British and Irish negotiators led by David Lloyd George, the British prime minister, and Arthur Griffith, Dáil Éireann’s minister for foreign affairs.

The two sides had been negotiating in London since 11 October. The frenetic final week of the talks ended with protracted meetings beginning on 5 December, during which Lloyd George threatened a renewed British war in Ireland unless the Irish negotiators agreed to the terms on offer. There are differing accounts of the precise words Lloyd George used, but the meaning was clear.

After a final round of discussions and revisions that stretched the talks beyond midnight, the Treaty was signed, according to Griffith, at 2:15 am on 6 December 1921.

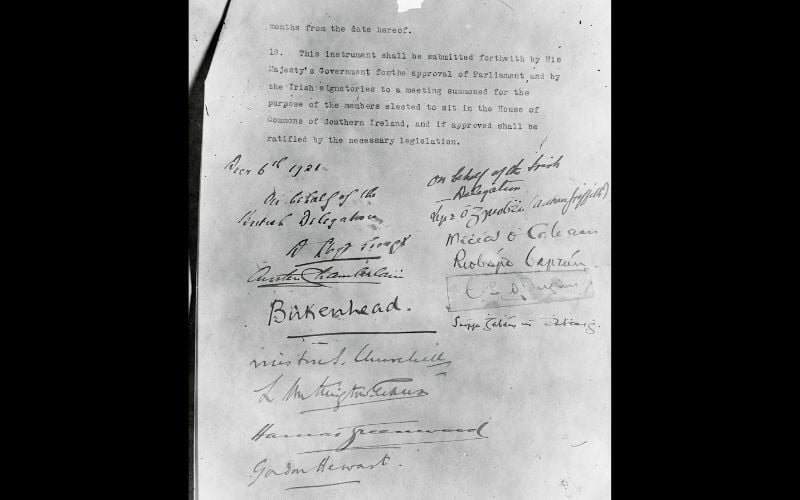

British and Irish signatures on the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 6th December 1921, which established the Irish Free State. (Getty Images)

Initially, the Treaty was only signed by those present at the final meeting in 10 Downing Street: Griffith, Michael Collins, and Robert Barton on the Irish side, and Lloyd George, Lord Birkenhead, Austen Chamberlain, and Winston Churchill on the British side.

The Irish delegation had made their headquarters at 22 Hans Place in the fashionable London district of Knightsbridge, to which they returned with their signed copy of the Treaty at 2:45 am. The last two Irish negotiators signed it there: George Gavan Duffy and Éamonn Duggan, who apparently signed it without taking the cigarette out of his mouth.

Based on the description left by Kathleen McKenna, Arthur Griffith’s personal secretary, this is the document retained today in the National Archives in Dublin, and which is at the heart of their new centenary exhibitio,n The Treaty, 1921: Records from the Archives.

There is also a British copy. Later in the morning of 6 December, Duggan took the Irish document to Dublin, but in the afternoon, the British called at Hans Place seeking the remaining signatures of the Irish plenipotentiaries for their own copy. The absent Duggan’s signature was cut from an autographed copy of a programme for a reception held for the delegation at London’s Royal Albert Hall in October and was pasted onto the British text, where it remains clearly visible. But regardless of cosmetic differences between the two copies, the substance remains the same.

The Treaty is over 2000 words long, consists of 18 articles, and established a self-governing Irish state after centuries of British rule. The first four articles defined the status of the Irish Free State that was to be created by the Treaty as having the ‘same constitutional status' as the autonomous settler colonies of the British Empire (the so-called ‘white dominions’): Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. In a concession to reassure the Irish negotiators, the Irish Free State was to have the same status as Canada. It would also have a royal representative modeled on the governor-general of Canada, and members of any new Irish parliament would have to take an oath requiring that they be ‘faithful’ to the monarch (article 4, in which the latter was specified, contained the first official usage of the term ‘British Commonwealth of Nations’).

Two key issues emerged during the negotiations in London. The first was Ireland’s future relationship with the British Empire. The British were not prepared to let Ireland break away from the empire lest it set a dangerous precedent; this was the issue on which peace or war hinged. The Irish Free State was to be a part of the British Empire, and this would, more than anything else, split the independence movement that had sought an independent Irish republic. The following few articles dealt with financial obligations, trade, and British military requirements. Then came articles 11 to 16, which dealt with the second key issue in the negotiations: the partition of Ireland and the existence of Northern Ireland.

It is often wrongly assumed that the Treaty partitioned Ireland. It did not: Ireland had been divided into two jurisdictions in 1920. During the negotiations, the Irish had sought concessions on what they described as the ‘essential unity’ of Ireland, as they felt that an accommodation with the British Empire could be acceptable if they could secure a route towards Irish unity. However, the British were not prepared to coerce or undermine the new Ulster Unionist government in Northern Ireland. In theory, the Treaty established a 32-county Irish Free State, but Northern Ireland was given the right to opt out, in which case a ‘boundary commission’ would determine the final border between north and south. This was the most that was on offer from the British. The Irish negotiators hoped that it would drastically reduce the size of Northern Ireland and make unity inevitable, but there was no guarantee this would happen. There were also provisions for a north-south ‘Council of Ireland’ to enable the governments in Dublin and Belfast to co-operate, but this never met.

The final articles dealt with the transition from British to Irish rule, which was to be managed by a ‘Provisional Government’. The Irish Free State was to come into existence on 6 December 1922, exactly a year after the Treaty was signed, and it did. But much else happened in the interim. By December 1922, Griffith and Collins were both dead, and a brutal and devastating civil war convulsed the 26 counties that became the Irish Free State. The British had been prepared to use force to ensure compliance with the Treaty and closed off avenues that might have led to any compromise between the pro- and anti-treaty wings of the republican movement, which would fight each other in the civil war. At the end of the negotiations in London in December 1921, the British may have gotten more of what they wanted, but the Treaty gave the Irish something that they could, in time, work with and build upon. Whether one agrees with it or not, the document signed in London on 6 December 1921 provided the basis for an independent Irish state, making that date a milestone in the struggle for Irish independence and the Treaty itself one of the most essential documents in modern Irish history.

*John Gibney is Assistant Editor with the Royal Irish Academy.

** Originally published in 2021, updated in December 2025.

Comments