Trinity College Dublin historian explores the anti-vaxxer movement, protesting vaccinations against smallpox in the early 1800s as scientists searched for a means of containing and eradicating the disease.

Among the many diseases that could kill you in 19th-century Dublin smallpox was the most feared. Parents dreaded the alarming signs of fever, vomiting, and severe skin rash, death rates in children could reach 80 percent. Survivors risked being left blind and facial scarring might be seen as a lucky escape. On Dublin’s streets, it was not unusual to see adults with pitted faces, the sign of a childhood infection. This common legacy of smallpox gives us the expression ‘pock-marked’.

People who survived smallpox were generally immune afterward, so inoculation was used to prevent infection. Infectious material, perhaps scabs or pus from an infected person, were applied to a small scratch in the skin. The patient would, hopefully, develop a less severe infection from which they would recover – and develop immunity. This was as risky as it sounds.

In 1725, Dr. Bryan Robinson treated five Dublin children by this "variolation" method, two of them died. So Edward Jenner’s discovery that inoculation with the much milder cowpox produced resistance to smallpox was a real breakthrough. His safer procedure, called vaccination - after vacca the Latin for cow - was first used in Ireland in 1800.

Jenner’s method became widespread. Free doses of cow-pox, in the form of needles impregnated with calf lymph, were provided to vaccinate the poor and the risky variolation method was outlawed. Vaccination was so successful that from 1853 it was made compulsory for all infants in the United Kingdom. This was a radical move for a British parliament. Parents who did not produce proof that their child was vaccinated were fined, and if they persisted the fines mounted up, resulting in the imprisonment of the most determined objectors.

This created determined opposition in Britain – but it had far less impact in Ireland. The British Anti-Vaccination League, established in 1853, attacked the state’s infringement on personal liberty and the medical risks involved. The law, they argued, was despotic and un-British as it gave the government power over citizens’ bodies. Parents had a God-given right to protect their child’s welfare, enforced vaccination was against Natural Law. (Interestingly, when the Canadian government tried to enforce compulsory vaccination on French Canadians in Montreal, rioters resisted this despotic "English" practice.) Campaigners claimed that animal matter, "the filth of the cowshed", was being injected into their children, along with other diseases such as syphilis. They alleged a cover-up by the medical profession to hide evidence of deaths from vaccination.

This British opposition was not mirrored in Ireland. Compulsory vaccination arrived here along with the registration of births, which began in 1864, and this may account for public acceptance. Neither nationalist politicians nor the Catholic church raised objections. In Britain, pressure from the anti-vaccination movement forced a change in the law. Parents who opposed childhood vaccination on moral grounds could claim exemption by appearing before a special tribunal. This introduced "conscientious objection" into British law; it would become more famous during the First World War (1914-1918) for men refusing compulsory military service.

Ireland was not included in this new vaccination exemption scheme, so an Irish Anti-Vaccination League emerged in 1898 to address this. However, it never achieved the same level of popular influence as its British counterpart. The public response in Ireland seemed to be a mixture of amusement and bemusement. The Southern Star newspaper in 1898 observed that: "Englishmen sneer frequently at Irish agitation, but to the Irish mind nothing could be more ludicrous than the anti-vaccination crusade."

The opposition had some support in Ulster, inspired by the ‘Natural Law’ argument and the unionist desire for British law to apply fully in Ireland. The Belfast Newsletter gave occasional coverage to the movement, but far less than British newspapers gave opposition there. Pockets of activism appeared in Dublin’s southern, unionist suburbs, and in Enniscorthy and Nenagh. George Bernard Shaw sent a letter of support to the League’s 1911 conference in Waterford describing the distribution of ‘dirty and dangerous’ calf lymph to children as ‘nothing short of attempted murder’.

An alarming outbreak of smallpox in Dublin focused public attention in Ireland. In 1902, from an initial case of one infected sailor arriving into a crowded tenement, smallpox began spreading through the community, threatening the entire city. Lethal outbreaks were claiming many lives in Liverpool and Glasgow, port cities trading regularly with Dublin.

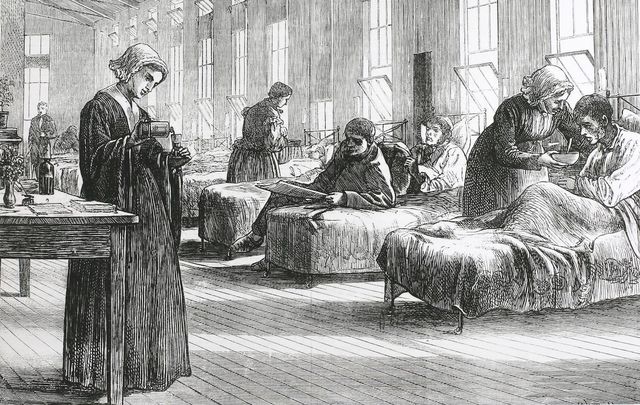

Dr. Charles Cameron, Dublin’s long-serving and renowned medical superintendent of health, took very vigorous action. He ordered the rapid construction of an isolated smallpox hospital. Close contacts were placed in a municipal refuge, their homes were disinfected and whitewashed, the clothing and bedding incinerated. Vaccination and re-vaccination played a key role. A poster campaign publicized new vaccination centers that operated late into the night. The posters also warned of fines for concealing cases of smallpox. By autumn 1903, after 360 cases, 33 deaths, and no new infections, Dublin could breathe a sigh of relief. The medicine was unpleasant but it had worked.

Small-scale opposition to vaccination survived in Ireland, enduring into the new state as an occasional letter to the press. By 1915 the editor of the Nationalist and Leinster Times reflected the weariness with the issue. Printing the final exchange of letters in the endless vaccination argument he wrote: "This correspondence must now close. So far as we can see, the arguments of laypeople … have been used to the fullest and a general meeting of the medical faculty might relieve the minds of the ordinary public." But perhaps the Registrar General for Ireland’s 1919 report was more conclusive. While smallpox persisted in England, Scotland, and Wales, there had been no death from smallpox in Ireland in over a decade.

Professor Ciarán Wallace, Trinity College Dublin, will speak as part of a public seminar ‘Population Health Advocacy: The Legacy of Sir Charles A. Cameron’, on 2 March 2021. Registration details here.

* Dr. Ciarán Wallace is a Historian and Deputy Director of the Beyond 2022: Ireland’s Virtual Record Treasury at Trinity College Dublin. The Trinity Long Room Hub Arts and Humanities Research Institute is Beyond 2022’s Public Humanities Partner.