An excavation is underway to search for the remains of Irish famine victims, 6,000 of whom died of typhoid fever along the banks of the St. Lawrence River in Montreal.

Within what looks like an everyday, average car park in Montreal, an investigation is currently underway to find the tragic “fever sheds” that once held hundreds of thousands of ill and impoverished Irish immigrants attempting to escape the Great Hunger in Ireland for a new life in Canada and America.

The mass graves of 6,000 people who died in the Canadian city after fleeing hunger and poverty in Ireland are somewhere under the car park. Yhe dreams of the Montreal Irish Monument Park Foundation w to find them were dashed last summer as the park where the future memorial was to stand was sold to Hydro-Québec for use as an electrical substation.

However, in a gesture to the Irish Hydro-Québec has now begun an archaeological dig to search for the remains of the buildings that housed the sick Irish, as well as for any human remains that may lie under the ground of the site where the new station was to be built.

Read more: Bravery of the Grey Nuns of Montreal during Great Famine honored

Digging down through over a century and a half of the city’s history, the excavation must first make its way through a football stadium first erected for Expo 67, a former neighborhood, and equipment left behind from workers who built the nearby Victoria Bridge, before they come to the era when the famine Irish would have been making their way to Canada aboard the coffin ships.

“We’ve had to peel off all these layers to see if the old stuff is still there,” explained Hydro-Quebec archaeologist Andre Burroughs to the Toronto City News.

To begin the dig, the original pathway of the St. Lawrence had first to be established, having altered itself some 400 to 500 meters over the last two centuries as a result of human activity. Historic maps then had to be compared to current pictures to see was there any possible similarity that could give them a hint as to where the sheds would have been constructed.

Six thousand Irish buried in Montreal, the largest famine grave outside of Ireland.

Although no skeletal remains have yet been found, they have found traces of lime, which it is believed was sprinkled on graves at the time to speed decomposition.

“We know that there are patches of that (1847) layer that are left, but one of the objectives is to make sure the burial sites didn’t overflow on this plot,” Burroughs said of the possibility that the remains may be buried a little further south, closer to the current Black Rock memorial placed there.

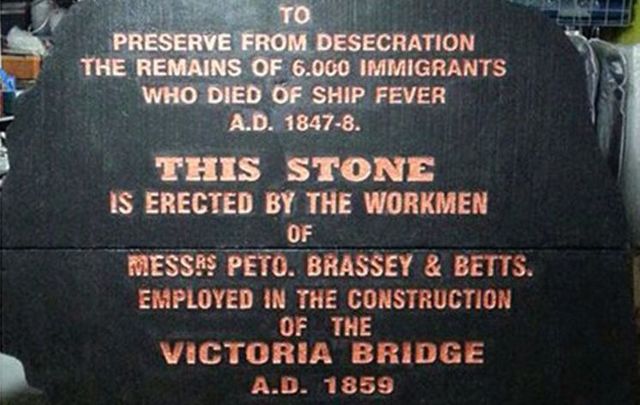

The grave sits in an industrial zone at the foot of the Victoria Bridge in Montreal with little indication that it holds host to the grave of 6,000 Irish and Canadian people.

Many Irish lost their lives here during the typhus epidemic of 1847, a year that is named Black ‘47 in Irish history in memory of the worst period of the Irish Famine and the vast numbers of Irish leaving the country for foreign shores.

Due to the lack of information on the symptoms of typhus, many sick people were considered healthy and allowed to continue on their journey from the Canadian quarantine station at Grosse Ile to the next stop of Point St. Charles in Montreal.

The city was not prepared for the flocks of sick and dying Irish, however, in what was to be one of the hottest summers on record in Montreal. By the end of this “Calcutta summer”, 6,000 lost their lives, including many Canadians who had ventured into the Irish neighborhoods in an attempt to save the famine refugees.

The Prince of Wales Laying the Last Stone of the Victoria Bridge Over the St. Lawrence. Montreal, Canada. Image: Public Domain / WiikiCommons

Despite being the largest single burial site of the Great Hunger in the world outside of Ireland itself, the grave is currently only marked with a 10-foot tall, engraved stone stained black by car fumes and nicknamed the Black Rock. As such, the Irish in the area established the Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation in 2012 with the aim of turning the nearby car park into an official memorial to the thousands of Irish buried here and the Canadians who helped them.

Read more: Montreal’s Irish fight for memorial to the 6,000 famine immigrants who died of typhus

“They knew that going to help those Irish could be a death sentence, and it didn’t stop them,” explained Fergus Keyes, co-founder of the Montreal Irish Memorial Park Foundation.

“Pretty much every language and cultural group sent representatives to help the Irish.”

The group were hugely disappointed when the sale of the land was announced earlier this year after years of petitioning local politicians, but they are happy, nonetheless, that proper excavation work in finally underway on the site to check for remains.

“It’s something we’ve always wanted to do, because there’s always been a curiosity: are there any bodies under the parking lot?” Keyes asked.

He also believes there is a good chance that Hydro-Québec will discover something. The company has promised to leave the remains undisturbed if possible, if this proves to be true.

Should the land have become a memorial park to the Famine Irish? Let us know your thoughts in the comments section, below.

Comments