In October 1845, just over a month after the first signs of potato blight had been reported in Ireland, a visitor to the west of Ireland witnessed a funeral taking place at the 15th-century Quin Abbey, in County Clare.

There amid the picturesque ruins, the writer saw "peasants in long blue or scarlet mantles, white caps or kerchiefs tied over their heads" kneeling motionless in silent prayer on the tombstones. Before long the "mournful chant of the death wail" reached the writer's ears.

The burial taking place was that of an 18-year-old girl who had died from fever. Three days earlier the deceased had overseen the burial of her father and that of her sister two weeks previous. Such tragic circumstances left a lasting impression on the writer but within a short period of time death would become an overwhelming feature of everyday life in Ireland.

Hunger brought about by the failure of the potato crop was exacerbated by the onset of fever during the winter of 1846 and the spring of 1847. Soon, death overwhelmed people and normal funeral practice was quickly forgotten.

National and provincial newspapers teemed with reports of mass death across Ireland. In January 1847, it was reported that there were ten funerals a day in the west Kerry village of Dingle. In the same month in the parish of Kilmore, near Skibbereen in County Cork, 14 people were buried on the one day. The following month, on a single day, 13 funerals passed through the town of Killarney. Soon there would not be enough people to help in the burial of the dead, while many more were afraid to do so.

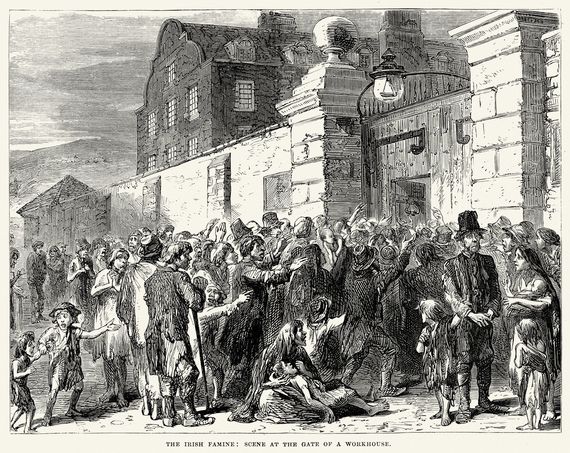

An illustration of Irish gathered outside a workhouse during the Famine.

In Cork city, the constabulary was required to carry out the burial of 21 people where there were no family members present to oversee proceedings. At Elphin, County Roscommon a poor man weak from fever endeavoring to bury his son fell into the grave dead.

By August, the number of burials in the town of Tuam, County Galway was described as "almost incredible". In Dublin, Cork and other provincial town’s advertisements were placed seeking land for the opening of the burial ground.

The Freeman’s Journal newspaper claimed that Fr Theobald Mathew had decided to close the city’s burial ground which had received the bodies of over 10,000 people since the previous autumn. Many of these were buried with coffin or cloth. It was a similar scenario elsewhere. At Kilgobbin, in County Kerry, in March 1847 seven burials took place on one day without coffins. There was such a demand for coffins that the County Offaly land agent, Francis Berry, wryly commented that "the coffin makers" were making a fortune during this period of fever and pestilence.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Almost everywhere the resources of local relief committees were exhausted. At the first meeting of the Rathkenny Relief Committee, in County Cavan, in March 1847, their initial business was completely taken over by the necessity to order extra coffins for the dead.

The committee ordered that for convenience, coffins should be made in three sizes: 6 feet 3 inches; 5 feet 8 inches and 4 feet. Everybody, young and old, were to make do with these sizes. The following month in Cork city the want of coffins was evident in the Jail Road district where the police supplied more than 50 coffins in a week but acting on the orders of their superiors declined to provide any more. The Beamish family, prominent brewers in the city, came to the aid of the poor supplying coffins until the establishment of a new relief committee.

While want of coffins continued to be a problem, in hundreds of cases people neither had the energy or the inclination to carry out the burial properly. The dead were buried barely a foot under the ground which posed problems when animals roamed into graveyards and burial grounds. In some instances horses, cattle and sheep easily disturbed these shallow graves.

In County Kerry, a report in 1847 claimed that the bowels of one corpse could be seen after an animal had dug below the surface. In the same county, at Aghadoe burial ground it was pigs and dogs who were exhuming the corpses. In their defense, people claimed that these shallow graves were necessary to allow them to be easily re-opened in order to inter other family members. The exhumation of bodies for fresh burials also posed a problem to public health and contributed to further disease which was spread by those in attendance.

In some instances, there were little respect paid to the dead. At Mountmellick in County Laois, the guardians were accused of burying people in a pit and in some cases two to a coffin. No humanity was shown to these people in their final resting place. Indeed, one of the guardians, William Pigott claimed that he had witnessed "nine coffins lying beside a hole, ready to be pitched in".

While touring the country to provide relief, Fr James Maher, a county Carlow priest witnessed many who were left unburied on the side of the road or in the ditch. According to Maher, during a visit to the west of Ireland, he witnessed a poor woman dead on the roadside, near Westport and who remained there for a number of days unburied on the highway; a stone at her head and another at her feet reflecting that she had left this world. Likewise, at Knocksaxon, in the parish of Straide he witnessed the body of Rose Hoban which lay for eight days dead before she was interred.

The frequency of death meant that towards the end of the summer of 1847, a witness to a funeral near Skibbereen claimed that the only people in attendance were those who carried the coffin. It was a similar situation in Belfast where funerals passed with "so few attached, either sick themselves or afraid of contracting the contagion". As the people stopped attending, the traditions soon ended. In County Kerry, it had long been a tradition that women present at funerals would be heard crying and wailing as the body of the deceased was lowered into the ground. Now in 1847, as a man who witnessed eleven burials in one day in Aghadoe noted, all of that had ceased.

Instead, the people were interred ‘silently and sadly’ and nobody spoke a word.

*Dr. Ciarán Reilly is a historian of 19th and 20th-century Irish history at Maynooth University. You can follow him on Twitter @ciaranjreilly.

* Originally published in April 2020, updated in Nov 2023.

Comments