On August 19, 1876, the Catalpa rescue reached a conclusion as the whaling ship docked in New York Harbor, having successfully carried six Fenian revolutionaries from a penal colony in Australia.

It began with a letter. In 1873 John Devoy, the famed Irish rebel leader, and exile received a smuggled communication in his New York office from the former Fenian James Wilson, who was imprisoned with other Irish political prisoners half a world away, in the dreaded Fremantle penal colony in Western Australia.

"What a death is staring us in the face," wrote Wilson, "the death of a felon in a British dungeon, and a grave amongst Britain's ruffians. I am not ashamed to speak the truth, that it is a disgrace to have us in prison today.

"A little money judiciously expended would release every man that is now in West Australia. Think that we have been nearly nine years in this living tomb since our first arrest and that it is impossible for mind or body to withstand the continual strain that is upon us. One or the other must give way."

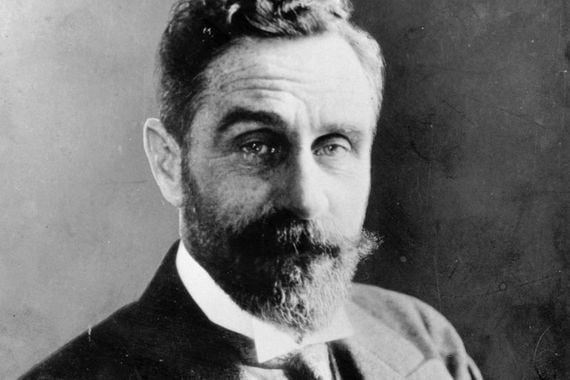

Roger Casement.

To underline this message Wilson added, "Remember this is a voice from the tomb. For is this not a living tomb? In the tomb, it is only a man's body that is good for worms, but in this living tomb the cankerworm of care enters the very soul."

Wilson's powerful words moved Devoy, and he immediately resolved to help him. As a journalist for The New York Herald and an active member in Clan na Gael, Devoy was singularly well placed to take action on Wilson's behalf.

At the very time, Devoy received the secret letter the fight for Irish independence had reached a low point. But in reading Wilson's entreaty, Devoy realized that here was an unfettered cry from the heart, a cry that had the power to move all who heard it.

It was also, Devoy realized, a bracingly political speech that had the power to boost morale and to bring the fight for Irish independence back into focus.

In Ireland in the early 1860s, James Wilson had joined the 5th Dragoon (British Army) Guards. But in secret he also became a Fenian, taking an oath to be obedient to his leaders, and to do his utmost to secure a democratic independent Irish Republic.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

To that end, he deserted with conspirator Martin Hogan in November 1865 after they had secretly enrolled many other Irish soldiers in the organization. But then, as so often in Irish history, local informers gave away the details of renewed Fenian activities to the British forces and Wilson was quickly arrested.

He was court-martialed in Dublin on February 10, 1866, where he was found guilty of mutinous conduct and received a sentence of death, which was later commuted to life imprisonment in Fremantle prison.

It was, in a real sense, a kind of death in life. Wilson was placed on board the Hougomont bound for Fremantle with the other Fenian prisoners. When they arrived in Australia, on the advice of the Catholic chaplain, civilian Fenians were allowed to work together away from the other convicts, but a special contempt for British military deserters like Wilson was expressed by dispersing them among convicts, much to their disgust.

Years passed and by 1869 more than half the Fenian convicts were granted royal pardons, but not a single ex-British soldier was among them. The Duke of Cambridge, it was rumored, had prevented Prime Minister Gladstone from showing them a shred of clemency.

It soon became obvious to Wilson and the others who remained that they would never receive a pardon. The only choice was to serve out their terms or escape.

For Wilson the choice was clear. He wrote his secret letter requesting help immediately.

Although it would take a year coming, help arrived in the shape of the Catalpa, an American whaling ship hired by Devoy from secret donations made by Irish independence organizations across the United States. Amazingly, informers did not foil the daring rescue plan and the ship reached Australia without mishap.

Fremantle was - and still is - an imposing prison. Situated in hostile terrain, there was very little opportunity for escape because on one side there was hundreds of miles of inhospitable (and deadly) desert and a shark-infested ocean on the other. The British guards weren't worried about people running away, assuming escape would be an impossibility.

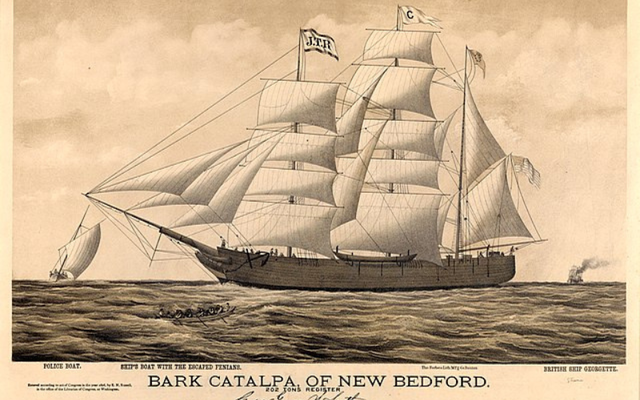

The rescuers rowed to shore to collect the six waiting Irish convicts who had left their posts while working outside the secured area. Their Irish rescuers were waiting with wagons and weapons. But like all good rescue dramas, complications cloud their flight. When the freed prisoners began to row back to the Catalpa a sudden unexpected storm meant they could not reach the ship for another day, by which time the alarm had been raised and British police ships launched.

The British commandeered a gunboat called the Georgette, which they pulled alongside the Catalpa requesting that the prisoners be handed over. Captain Anthony, the ship's celebrated American captain, defiantly refused this request and raised the American flag, warning his pursuers that the Catalpa was in international waters and could not be boarded.

If they fired on the Catalpa they would be firing on the U.S. This parry enraged the Georgette's British captain, who conceded reluctantly.

Eventually, the Georgette was forced to give up the chase, although all on board were convinced they had seen the missing men. Shortly after, as John Devoy predicted, the Catalpa rescue bolstered Irish morale across the globe and spurred the fight for Irish independence, which was finally won in 1922.

Devoy lived long enough to see that lifelong ambition realized and, half a century after being exiled himself, he returned to the country he had fought so hard to free.

* Originally published in Aug 2016. Updated in 2023.

Comments