Easter Rising leader Padraig Pearse was ultimately put to death for his involvement in the uprising. Here we take an in-depth look at the life of Pearse and his contribution to Irish history.

Editor's Note: The 1916 Easter Rising, the rebellion that took place over the course of five days in Dublin and forever changed the course of Irish history, may have led to the execution of its leaders but, now more than ever, we remember those heroes who put their lives on the line for Irish independence. Below, Dermot McEvoy takes an in-depth look at the life of Pearse and his contribution to Irish history.

Padraig Pearse

Patrick (Padraig) Pearse was born on November 10, 1879, at 27 Great Brunswick (now Pearse) Street. (The building is still there and has been repaired to the way it looked in Pearse’s youth.) His father James was English and his mother Margaret (née Brady) Irish. The father’s stonemason business, also at #27 Brunswick, specialized in ecclesiastic monuments. Pearse was baptized around the corner at St. Andrew’s and educated at the Christian Brothers School at Westland Row. He received his B.A. from Royal University and a law degree from the King’s Inn in 1901 (his law career consisted of one case, which he lost).

From all indications Pearse as a boy was a solitary figure—he prefers reading a book to playing with other children—with his brother Willie his closest friend. His reticence may have been caused by a cast in his right eye which was the reason he was almost always photographed in profile. This may also explain his extreme shyness where women were concerned.

His mother’s family were Irish speakers from County Meath and at 16 he joined the Gaelic League, eventually becoming the editor of its newspaper. According to Richard Ellmann, he was the Irish teacher to a young man by the name of James Joyce. (Imagine, in one room, Ireland’s ultimate ascetic and its greatest satyr!) Showing no interest in the law, Pearse, with his love of the Irish language, turned his attention to education. He was a critic of the education system in Ireland which he believed taught Irish children how to be good Englishmen (he called it “The Murder Machine”).

Thus he started Scoil Éanna (St. Enda’s School) in 1908, eventually settling at the Hermitage in Rathfarnham, which is today the location of the Pearse Museum. The school was a family affair—besides Thomas MacDonagh who served as assistant headmaster, the faculty included his brother Willie, his sisters Mary Brigid and Margaret, and his mother acted as housekeeper. It focused on a bilingual (Irish/English) curriculum and was a success academically, but put tremendous financial stress on Pearse. In 1914 this forced Pearse to go to America on a speaking tour to raise money. There he met John Devoy who he referred to as “the greatest of the Fenians.” The trip raised a much-needed £1,000 for St. Edna’s. He even got time to play tourist, visiting the just-opened Woolworth Building which was then the tallest building in the world.

Pearse’s early politics were moderate: he was in favor of the Irish Parliamentary Party and Home Rule. But the IPP’s failure to bring Home Rule home turned Pearse more militant. He joined the Irish Volunteers in November 1913. At first, Tom Clarke—the puppeteer who was orchestrating this new Irish militancy—was initially suspicious of Pearse because of his previous moderate political views. Clarke needed a frontman for the movement. He and Seán MacDiarmada, the two guys pushing the envelope, couldn’t be the face of the movement because of their jail records and their penchant for inciting havoc against the British. MacDiarmada urged Clarke to let Pearse give the oration at the Wolfe Tone Commemoration in 1913 and Clarke was so impressed with Pearse he exclaimed, “I never thought there was such stuff in Pearse!” Clarke had found his perfect frontman.

Perhaps Pearse foresaw this future role in a poem he wrote called “The Rebel”:

I am come of the seed of the people, the people that sorrow

That have no treasure but hope,

No riches laid up but a memory

Of an Ancient glory.

My mother bore me in bondage, in bondage my mother was born,

I am of the blood of serfs;

The children with whom I have played, the men and women with whom I have eaten,

Have had masters over them, have been under the lash of masters,

And, though gentle, have served churls…

… And I say to my people’s masters: Beware,

Beware of the thing that is coming, beware of the risen people,

Who shall take what ye would not give.

Did ye think to conquer the people,

Or that Law is stronger than life and than men’s desire to be free?

We will try it out with you, ye that have harried and held,

Ye that have bullied and bribed, tyrants, hypocrites, liars!

Pearse shot into prominence with his oration at the grave of the old Fenian Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa in Glasnevin Cemetery on August 1, 1915. Standing next to John MacBride and Tom Clarke—all three would be shot the first week of May 1916—he concluded his funeral oration with a warning to the British:

“…The defenders of this realm have worked well in secret and in the open. They think that they have pacified Ireland. They think that they have purchased half of us, and intimidated the other half. They think that they have foreseen everything. They think that they have provided against everything; but the fools, the fools, the fools! they have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace.”

In the months ahead Pearse would work with Clarke, MacDiarmada, Plunkett and Connolly in planning the Rising. By Easter Monday he was named President of the Provisional Government and as Commandant-General was Commander-in-Chief of the Irish Volunteers. At noon on Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, he stood in front of the GPO and read the Irish Declaration of Independence, which he had written:

POBLACHT NA hÉIREANN

THE PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC

TO THE PEOPLE OF IRELAND

IRISHMEN AND IRISHWOMEN:

In the name of God and of the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of nationhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom…

We declare the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies, to be sovereign and indefeasible. The long usurpation of that right by a foreign people and government has not extinguished the right, nor can it ever be extinguished except by the destruction of the Irish people. In every generation the Irish people have asserted their right to national freedom and sovereignty; six times during the past three hundred years they have asserted it in arms. Standing on that fundamental right and again asserting it in arms in the face of the world, we hereby proclaim the Irish Republic as a Sovereign Independent State, and we pledge our lives and the lives of our comrades in arms to the cause of its freedom, of its welfare, and of its exaltation among the nations…

We place the cause of the Irish Republic under the protection of the Most High God, Whose blessing we invoke upon our arms, and we pray that no one who serves that cause will dishonor it by cowardice, inhumanity, or rapine. In this supreme hour, the Irish nation must, by its valor and discipline, and by the readiness of its children to sacrifice themselves for the common good, prove itself worthy of the august destiny to which it is called.

In the GPO, Pearse was his usual distant self and most of the military decision-making was left up to Connolly. He did interact with all the Volunteers and gave a few little speeches that lifted the spirits of the men and women. By Friday he left the blazing GPO for Moore Street with the rest of the leadership. It was there that he decided to surrender to General Lowe. In captivity in Richmond Barracks before being moved to Kilmainham for execution, Piaras Beaslai remembers how Pearse “sat on the floor, deep in his own thought, so full of them that he noticed nothing around him.” His distant demeanor recalled what Pearse had once written about himself: “I don’t like that gloomy Pearse. He gives me the shivers.”

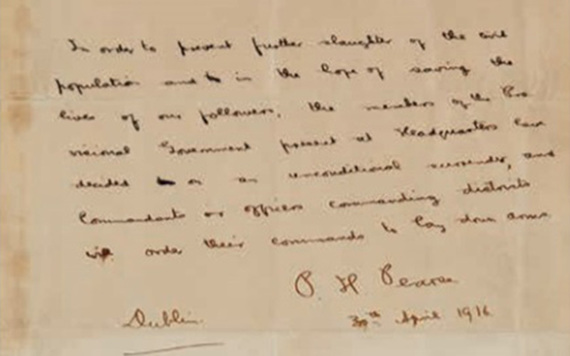

At his court-martial, Pearse stated: “My sole object in surrendering unconditionally was to save the slaughter of the civil population and to save the lives of our followers who had been led into this thing by us. It is my hope that the British Government who has shown its strength will also be magnanimous and spare the lives and give an amnesty to my followers, as I am one of the persons chiefly responsible, have acted as C-in-C and president of the provisional government, I am prepared to take the consequences of my act, but I should like my followers to receive an amnesty. I went down on my knees as a child and told God that I would work all my life to gain the freedom of Ireland. I have deemed it my duty as an Irishman to fight for the freedom of my country.”

He was the first of the 1916 rebels to be executed at 3:45 a.m. Fifteen more would follow.

Pearse's surrender letter. NLI

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany" (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on his website and Facebook page.

* Originally published in 2016. Updated in April 2024.

Comments