One a former farmer in America, another who was already dying! Here are some incredible facts about some of the Easter Rebellion leaders.

On this week, 105 years ago, an armed Irish republican insurrection was mounted against British rule in Ireland, aiming to establish an independent Irish Republic. Sixteen of the Easter Rising leaders were executed in May 1916. Here are some interesting facts about the leaders of the Easter Rebellion.

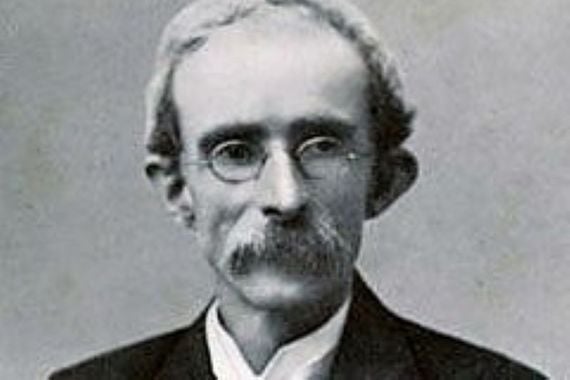

Why Patrick Pearse was always photographed in profile

Patrick Pearse was always photographed in profile and many wonder why.

The reason is that Pearse had a pronounced squint in one eye and this made him camera-shy. It also made him determined only to be photographed from the side, to conceal what he felt was such a disfiguring squint.

Read more

In family pictures or pictures of him with groups of colleagues, Pearse always struck a sideways pose even though everybody else in the picture would be looking straight at the camera.

A new book of pictures taken throughout Pearse's life clearly shows this. It is called “Patrick Pearse A Life in Pictures” published by Mercier Press.

But the book also includes a rare image of Pearse looking at the camera face on, which, although somewhat blurred, shows the extent of his squint.

The book, compiled and written by the curator of the Pearse Museum, Brian Crowley, says that Pearse was "very self-conscious" about his eyes.

"It appears to have affected him from birth and was hereditary. Whenever possible, he made sure that he was only photographed in side profile," Crowley writes.

Joseph Plunkett was already dying of “galloping consumption”

Joseph Plunkett.

Joseph Plunkett was dying of what was then called “galloping consumption” (a wasting disease, especially pulmonary tuberculosis) in the GPO and had to be dressed by a young Michael Collins for the last two days of combat.

He had just been operated on and was very weak but no one fought more bravely according to Volunteer accounts. With Connolly badly injured much of the defense fell to Plunkett who did not shirk his task despite his illness.

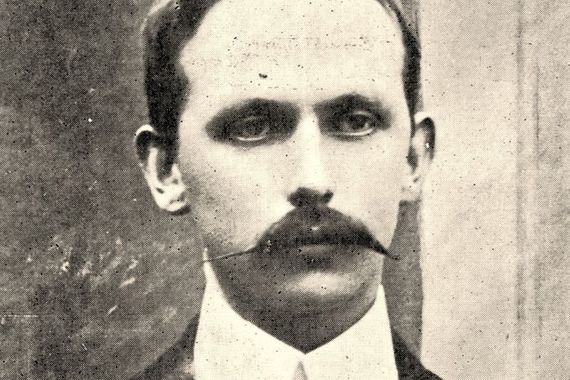

Thomas Clarke’s American years as a farmer

Thomas Clarke.

Clarke, born in England, settled in Ireland and became a fierce opponent of British rule. He chose the emigration route and in 1881 set sail for the US. Immediately after arriving, he joined Clann na Gael, the successor to the U.S. branch of Fenian Brotherhood.

His first job in the US was as a night porter in the Mansion House Hotel, in Brooklyn. After that, he worked as an explosives operative on construction projects where he learned to handle and set explosives. His expertise in this area was recognized by the leadership of Clann na Gael as a valuable asset that would augment the dynamite campaign underway in England to bring the war to the mainland.

In 1883, Clarke was sent to London to join an active service unit deployed to bomb high-profile sites in London and elsewhere throughout England. Among the targets bombed were the posh Carleton Club, the police headquarters at Scotland Yard, and the British House of Commons. The London Bridge was also on the list, however, a premature explosion killed two of the attackers.

Clarke was betrayed and arrested in April of 1883 and tried at the Old Bailey the following June under the notorious Treason Felony Act. He was found guilty and sentenced to penal servitude for life. He served 15 years in brutal conditions in Pentonville prison before being released under a general amnesty for Fenian prisoners in 1898.’

Read more

After his release, he returned to Ireland and was made a freeman of the city of Limerick. It was there that he met his future wife, Kathleen Daly, niece of John Daly, the Fenian leader whom Clarke had met in prison, and the sister of Edward Daly, commandant of Dublin's 1st battalion who fought in the Four Courts during the Easter Rising of 1916. Daly was executed on May 4, 1916.

Unable to find work in Ireland, he returned to the U.S. in 1899 with Kathleen Daly whom he married in 1901. They settled in Brooklyn and became a U. S. citizen in 1905. During his second stay in the U.S., he worked with John Devoy in the offices of the Gaelic-American newspaper. He moved to Suffolk County in Long Island in 1906 and purchased two plots of land totaling 60 acres in the Town of Brookhaven.

In May of 1987, the AOH and a number of trade unions erected a two-ton obelisk of Wicklow Granite on the land in Manorville once owned by Clarke.

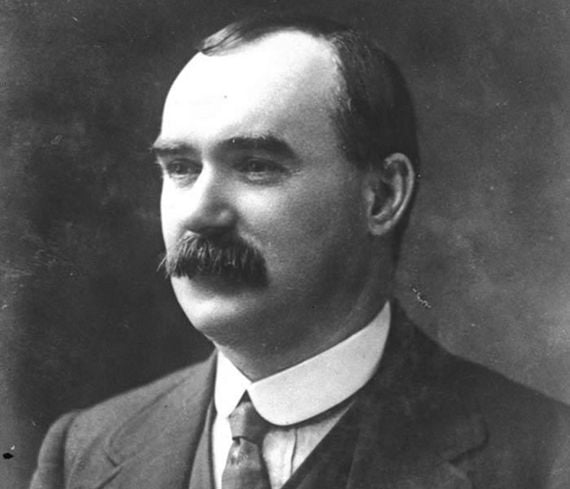

James Connolly, the last moments by his daughter Nora

James Connolly.

An account of what happened appears in a witness statement that Nora Connolly gave, and that is among the collection of James Connolly’s personal papers that the National Library of Ireland has just put online, to mark the centenary of 1916.

“My mother and I . . . were driven to Dublin Castle,” Nora said. “On entering we were directed to a flight of stairs. At the top of the stairs were six soldiers with fixed bayonets, and on the floor about a dozen more were lying on mattresses.

“We passed through the soldiers and entered an enclave where there were two soldiers with fixed bayonets. They stood aside to let us enter the door. When we entered my father was lying in the bed with his head turned to the door.”

It is clear from Nora’s testimony that her mother still hoped that her husband’s life might be spared. She was shocked when he told her that he was to be executed. Connolly told his wife, “Well, I suppose you know what this means.” Lillie responded, “Not that James, not that.”

Nora continued: “My father said, ‘Yes, for the first time I dropped off to sleep. And they wakened me to tell me that I was to be shot at dawn.’ ”

Lillie said, “Your life, James, your beautiful life.”

“Well, Lillie,” he answered, “hasn’t it been a full life, and isn’t this a good end?”

Nora told him of the executions of Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh and others. “He was silent for a while. I think he thought that he was the first to be executed. Then he said, ‘Well, I am glad that I am going with them.’ ”

Nora also told her father about the clamor to have the executions stopped. “I told him that it had been in the papers that there was to be no more shootings. ‘England’s promises, Nora, you and I know what that means.’ ”

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

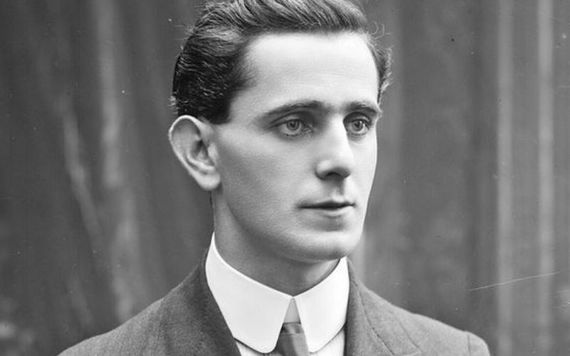

Of the five sisters of Sean Mac Diarmada, four came to America

Sean Mac Diarmada.

Sean Mac Diarmada signed the proclamation and was executed. Unable to bear the grief his siblings emigrated en masse to the US, with the exception of his sister Maggie, who remained in the family home in Kiltyclogher, County Leitrim. She wrote to the Department of Defence in June 1937 to say she’d read in the Irish Press newspaper that a new army Bill allowed for pensions to be paid to the sisters of the 1916 Proclamation signatories. “I never heard a thing about it until I saw it on the paper. I never got a penny. I expect I should be entitled to it as he always helped me while he was alive,” she wrote.

In order for her to receive a pension, she had to verify her identity. The matter was so sensitive that Garda commissioner Eamon “Ned” Broy was asked by the minister for defense to make “discreet inquiries”, without approaching Mrs McDermott (she was also married to a McDermott), as to whether or not she truly was the sister of Seán Mac Diarmada.

Maggie McDermott eventually received a £100-a-year pension from the State. According to the files, in 1938 she was the only one of Seán Mac Diarmada’s two brothers and five sisters still living in the country that he had fought and died to liberate from the British.

His other sisters in the US – Rose, Catherine, Bridget (Bessie) and Mary Anne– also received £100 a year each.

Eamonn Ceannt played the pipes for the Pope

Eamonn Ceannt.

"Eamonn Ceannt was an intellectual, a native of Galway, where he was born in 1881. At heart a fiery gospeller for independence, his actual manner was reserved, almost aloof. He had great enthusiasm for the cause, but outwardly it was shown to only a few. His working hours were spent as a clerk in the City Treasurer’s office while every moment of his spare time was devoted to the great ideal of independence for Ireland.

"He was recognized as one of the best teachers of Irish and he had music, his native music especially, in his soul. He was also a good athlete and in the year 1908 he was a member of a party of Irish athletes visiting Rome for the Jubilee celebrations in honor of His Holiness Pope Pius X. While there he was invited, as a piper, to play before the Pope. Ceannt had an impressive military bearing, and as Commandant of the Fourth Battalion during the Rising fully displayed his military abilities."

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

* Originally published in March 2016.

Comments