A unique concept is rooted in the Irish psyche—respectability. Respectability can mean many things, but it meant only one thing among Irish Famine immigrants: financial security. Whether working as a street peddler and putting money in the bank or owning your own business and putting money in the bank, there was only one way to achieve respectability—saving your money.

In Tyler Anbinder's "Plentiful Country: The Great Potato Famine and the Making of Irish New York", the reader is transported to witness this yearning for respectability among our famine ancestors. Through meticulous research, Anbinder recreates the socio-economic climb of the Irish who arrived in New York during Ireland's Great Hunger, 1845 – 1852.

As you may have already guessed, money is how they ascended the ladder and how Anbinder traced their ascent in combination with census records and dedicated amateur genealogists.

The Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank (EISB) records are a treasure trove of details about the Irish who made deposits into their bank accounts when it opened in 1850. Anbinder provides us with information that bank clerks used to confirm the identity of each depositor.

Think of these details as today's passwords for phones or computers; only the depositor would know them: the name of the ship that delivered them to the port of New York, the date they arrived, family members traveling with them, and family members who already lived in America, to name a few details. Combined with census records and having successfully traced descendants of some depositors who expanded on their histories, Anbinder tells how some Irish Famine immigrants achieved financial success, and others lost it.

The records are available at the New York Public Library, but Kevin J. Rich compiled the records of solely Irish depositors into four volumes.

It was a pleasant surprise for someone interested in reading about Ireland's Great Hunger to read a few success stories about famine immigrants. Although the Irish depositors in the EISB represent only five percent of the Irish living in New York at that time, it is essential to keep the remainder of that percentage in our sights and acknowledge that 95% of the Irish who were delivered to the port of New York during the years 1845 – 1852 suffered greatly.

Anbinder estimates that number at 960,000. Of that number, 20-25% died, either on arrival or later on, when they came in contact with diseases such as typhus ("Irish Fever") and work-related diseases. The city was a Petrie dish for many rural Irish immigrants, exposing them to dust particles and germs they had never encountered in the Irish countryside. Between 192,000 to 240,000 Irish Famine immigrants died on arrival or after working for a few years and contracting illness in this "plentiful country."

From the highly organized chain migration practiced by the natives of Killybegs, County Donegal, and Bodoney, County Tyrone, to the meteoric rise of a pool table manufacturer who made his home in Darien, Connecticut, and the meteoric rise and fall of a wholesale liquor retailer who made his home in Stamford, CT, I found myself unable to stop reading this book.

Anbinder gave a talk about his research at the American Irish Historical Society in New York on Thursday, April 18, 2024. I asked if there were any relevant lessons about immigration gleaned from his study of this period. According to Anbinder, the biggest lesson is that there was always anti-immigrant sentiment when refugees or immigrants arrived in America. The Irish were not the first refugees and were not the first to experience racism either. It is a sad lesson, one we seemed doomed to repeat.

My takeaway, and as they say, hindsight is 20/20, was to move to the environs mimicking where you grew up. If you were from rural Ireland, go west. If you have a skill, use it and expand on it, like the millionaire pool table maker. It goes without saying, women had a more challenging time than men. However, as Anbinder correctly points out, your character was the most significant determining factor of your success. Males and females alike had to work hard to save their money.

For the 5% of Irish who deposited money into their accounts in the Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank in the years after they left Ireland as victims of the Irish Famine, leaving behind family members who were starving or already dead, this nest egg of ten dollars, fifty dollars, or sometimes even more, provided a sense of security they would not have been able to achieve had they stayed in Ireland, and, as Anbinder says, provide "a path to middle-class respectability."

* "Plentiful Country: The Great Potato Famine and the Making of Irish New York", by Tyler Anbinder. Published by Little, Brown, and Company. Available to purchase on Amazon.

Loretto Leary is the secretary and a board member for Ireland's Great Hunger Museum of Fairfield. Leary is a freelance journalist and author.

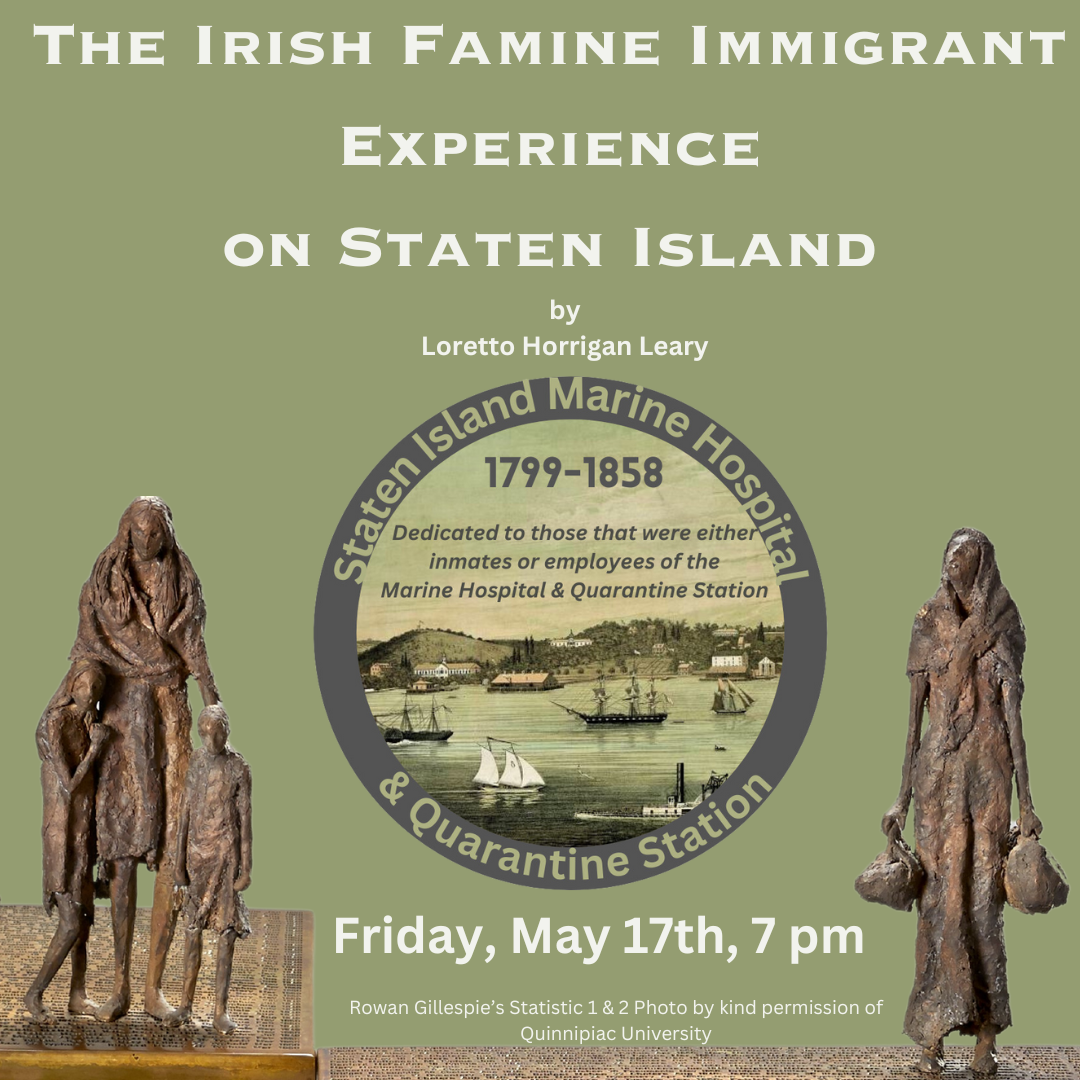

On Friday, May 17th, at 7 p.m EST., she will deliver a talk and slideshow presentation on the Irish Famine Immigrant Experience in Staten Island at the Gaelic American Club of Fairfield.

Irish Famine Commemoration Day is Sunday, May 19th, 2024.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments