Remembering the "peasant poet" Francis Ledwidge on the anniversary of the evacuation of Gallipoli.

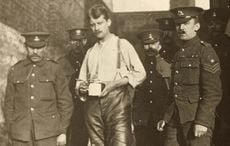

On the anniversary of the final evacuation from the Gallipoli campaign I think about all those who fought and died at Gallipoli, but also about Francis Ledwidge, who survived fighting in Gallipoli, Salonika and Egypt but who fell in the Third Battle of Ypres, aka Passchendaele, 31 July 1917, aged 29.

The ‘peasant poet’ landed in Gallipoli in July 1915, in the middle of a stalemate with neither side advancing, but who said it was ‘‘a great day which he would not have missed[1]”. He took part in the major August offensive, a joint allied attack on Suvla Bay of ‘The Foggy Dew’ fame: 'Twas better to die 'neath an Irish sky than at Suvla or Sud-el-bar’.

Many paradoxes apply to Francis Ledwidge. He left school at 13, worked as a miner and a labourer, started to write poetry as a teenager and went on to become one of Ireland’s best poets. He was a member of the Irish Volunteers and when the organisation split in 1914 he followed John Redmond’s National Volunteers lead to fight in WWI while many of the remaining Irish Volunteers, including many of Ledwidge’s friends, stayed at home to fight in the Easter Rising.

He ‘‘joined the British army because England stood between Ireland and an enemy common to our civilisation, and I would not have had it said that she defended us while we did nothing at home but pass resolutions.' In 1916 he stated ‘my own country has no place amongst the nations but the place of Cinderella’[2] a belief that may have coloured his choice when opting to side with a more influential nation, even if it was Ireland’s own colonizer, to attain Irish freedom through Ireland being rewarded with Home Rule due to its WWI war efforts.

In 1916 he also risked death by court-martial because of failing to report back for duty after the Easter rebels’ executions and for also speaking out at that time in favour of the rebels and the 1916 rising[3]. The idea of a firing squad dressed in the same British army uniform as he himself wore, executing the rebels was a moment of bitter paradox for him and inspired him to write an elegy ‘A Lament for Thomas MacDonagh’. Lucy Collins, UCD, felt that Ledwidge, by 1916 knew he had made the wrong decision by enlisting in the British army and we can sense the crystallisation of his disillusionment with the war in his beautiful elegy[4]. It is one of his most quoted poems and the first four lines are printed on Ledwidge’s own memorial:

He shall not hear the bittern cry

In the wild sky, where he is lain,

Nor voices of the sweeter birds

Above the wailing of the rain.

Perhaps exposure to the Anglo/Irish circle through his patron and mecene Lord Dunsay also made him more comfortable about enlisting in the British army, although Lord Dunsay himself, recognising Ledwidge’s enormous talent, had desperately tried to dissuade him. Suffering heartbreak may have also fuelled Ledwidge’s desire to leave Ireland; he enlisted in October 1914.

Ledwidge knew there would be no funeral or burial service for himself and the other soldiers. In the final lines of his poem ‘Soliloquy’ he predicts ‘‘a little grave that has no name, whence honour turns away in shame’. This line was actually censored from the poem in many publications and was Ledwidge’s prediction of his own fate and the fate of the thousands of Irish men who died in WWI.[5]

Ledwidge said that if he survived the war he hoped that he would write something that would live on. He did not survive, however, the words that he had already written have survived in our memories. In 1980 Seamus Heaney wrote the poem ‘In Memorium Francis Ledwidge’, which ‘acknowledged the complex personal choices that were made by Irishmen during WWI and the changing political landscape following the Rising in 1916[6]’.

Many considered Ledwidge to be a pastoral poet but Seamus Heaney also considered him to be one of the great war poets and penned ‘In Memoriam Francis Ledwidge’ in his memory. Here below one of the many references to Ledwidge’s enigmatic life as an Irish patriot and a WWI soldier.

I think of you in your Tommy’s uniform,

A haunted Catholic face, pallid and brave,

Ghosting the trenches with a bloom of hawthorn

Or silence cored from a Boyne passage-grave.

~~~~~~

[1] https://gallipoli.rte.ie/guides/francis-ledwidge/

[2] Brearton Fran, ‘All the strains / Criss-cross’: Irish Memory and the First World War, Caliban French Journal of English Studies, 33/2013, p. 105

[3] Collins Lucy, ‘A poet’s rebellion Francis Ldwidge and the 1916 rising’, YouTube.

[4]Collins Lucy, ‘A poet’s rebellion Francis Ldwidge and the 1916 rising’, YouTube.

[5] Smyth Gerard, ‘Francis Ledwidge : Farm labourer to war poet.’, The Irish Times, May 2015

[6] Cronin Mike, ‘Francis Ledwidge: the life & death of an Irish poet’, RTE

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments