Ironically, there are few places in Dublin more alive than Glasnevin Cemetery. Domhnall O’Donoghue delves into the history of Ireland's largest burial place.

Spanning 124 acres - and just a short bus ride north of the city centre - this graveyard is synonymous with heroic figures, instrumental in Ireland’s journey towards emancipation. There is a wealth of political titans buried here – namely, Daniel O'Connell, Michael Collins, Eamon de Valera, Charles Stewart Parnell and Countess Markievicz.

Glasnevin is also the final resting place of over a million people, including many Irish Famine victims.

“Glasnevin Cemetery tells the story of Ireland through the turbulent years of resurgent nationalism and the first one hundred years of independent statehood,” explains Luke O’Toole, Head of Development of Glasnevin Trust.

“Political leader Daniel O’Connell founded the cemetery in 1832,” says local man, Dara McCarthy - a charming, freelance guide with exceptional knowledge of the area. “Its original name was Prospect Cemetery, called after the small townland nearby.”

"Political leader Daniel O’Connell founded the cemetery in 1832."

At that time, Ireland was disentangling itself from Penal Laws, initially imposed to force Irish Catholics and Protestant dissenters to accept the established Church of Ireland. Through O’Connell’s campaigning, these oppressive laws were effectively abolished in 1829.

Before that, it was illegal for Catholics to be buried - they had no cemeteries of their own - and it had become standard practice for Catholics to conduct limited funeral services in Protestant churchyards or graveyards.

Despite this background, Dara reveals that Glasnevin Cemetery has, surprisingly, always been non-denominational.

“Many people felt that Glasnevin should be a Catholic cemetery, but O’Connell said no - arguing that that would be discrimination and exactly what the Protestants did to Catholics, Presbyterians and Methodists.”

Strolling through the cemetery, and receiving rain cover from the towering yew trees - which the Celts associated with death - I’m immediately struck by the wide variety of gravestones and sculptures. Austere high-stone erections sit alongside elaborate Celtic crosses - perfectly complemented by the modern Italian marble options.

* This article was originally published in Ireland of the Welcomes magazine. Subscribe here.

Tower of strength

Our first stop is the skyscraping O’Connell Tower, built to commemorate the cemetery’s founder and one of Ireland's most remarkable political figures, Daniel O’Connell.

Designed by famed architect Patrick Byrne, and using granite from the south Dublin suburb of Dalkey, work commenced on this iconic landmark in 1854 - seven years following O’Connell’s death. Taking 16 months to complete, the construction cost spiraled to £18,000 - or €15 million today.

“The design was based on Celtic round towers, which were bell towers created by monks,” Dara explains. “This tower is built on top of a mound, shaped as Newgrange - so you have Celtic and Catholic influences together.”

O’Connell was on a pilgrimage to Rome at the time of his death, hoping that the warmer climates would alleviate his bronchitis. However, he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage in Genoa and relinquished life in 1847.

The Kerryman’s final words were: “My body to Ireland; my heart to Rome; my soul to Heaven.” According to Dara, his friends took him literally.

“He was a lawyer, not known to mince his words,” he reveals. “They put his heart in a silver box and placed it in the Irish College in Rome.”

Where O’Connell’s heart is today remains a mystery, however.

Dara explains: “When the Irish College was moving, they discovered that the heart was gone. We don’t know what happened to it.”

A missing heart is not the only drama associated with O’Connell, post-death. In the 1970s, a bomb exploded at the tower’s base, which Loyalists planted in retribution for the IRA blowing up Nelson’s Pillar in 1966.

Following extensive restoration, the tower, along with the crypt, was recently re-opened and boasts 360-degree panoramic views of the Fair City.

Political giants

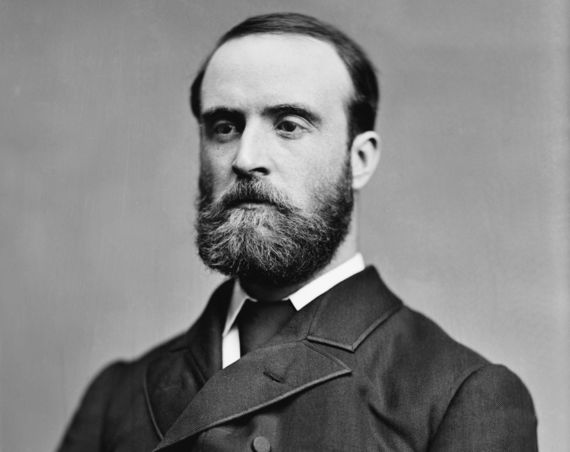

Charles Stewart Parnell - another seminal figure in Ireland’s journey to independence - is buried close-by in what was once considered poor ground. Leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, Parnell died in 1891 in near poverty, having been embroiled in an expensive divorce scandal, which also derailed his formidable career.

Charles Stewart Parnell

Still hugely popular with the Irish public, Parnell’s supporters convinced Glasnevin Cemetery to bury him despite the limited funds.

“Then, this area was poor ground, and nobody wanted to be buried here,” Dara says. “By burying a popular leader in an unpopular part of the cemetery meant those who respected him would want to be buried beside him.”

One such person was James Joyce’s father, John, who worked as an election agent for Parnell. In fact, in Ulysses, arguably the world’s greatest book, Glasnevin Cemetery - or Prospect Cemetery as it was then known - provides one of the backdrops. On Bloom’s Day, Dara reveals that Joycean fans - dressed in costumes from Edwardian times - re-enact parts of Ulysses here.

Another aspect of Parnell’s funeral could have been lifted straight from the pages of a novel. Reporting on behalf of the Freeman’s Journal was W.B. Yeats’ muse, Maud Gonne (who was later buried here). She wrote that the moment Parnell was lowered into the grave, a flash of light illuminated the night’s darkening sky.

“We thought she was exaggerating - or making it up because she liked Parnell,” Dara explains. “But, we checked with Dunsink Observatory, and there was a comet reported on the night he was interred, so it was true!”

* This article was originally published in Ireland of the Welcomes magazine. Subscribe here.

Rest in peace

In 2009, Glasnevin Trust and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission began identifying the graves of Irish service personnel who died while serving in the Commonwealth forces during both World Wars. Two memorials are located near the main entrance. Elsewhere, the Cross of Sacrifice marks the centenary of WWI.

Over 200,000 Irish people fought for the British during WWI when Ireland remained under their rule. Dara notes that while most enlisted for the paycheck; others hoped that Britain would reward their service by delivering their promise to give Ireland our own parliament.

Dara says: “Initially, the soldiers went away as heroes - sacrificing for their fellow man; trying to secure the Irish parliament; trying to get money to pay for their families here in Ireland.

“But a lot changed in Ireland during that time - notably the 1916 Rising where the British army executed Irish leaders in Kilmainham Gaol, turning them into martyrs.”

As a result, when Irish soldiers returned from the war, many viewed them as traitors because they had fought for the then despised British.

“For Americans, the closest analogy would be Vietnam,” Dara muses. “You go away heroes, the country changes its mind, they come back, and it’s a very controversial topic.”

The Big Fella

The next grave is the cemetery’s most visited - and, once again, imbued in Irish history: it belongs to Michael Collins - the country’s first de facto Prime Minister. The Corkman was instrumental in negotiating the 1921 Anglo-Irish treaty, which established the Irish Free State. However, it fell short of uniting the entire 32 counties on the island with six counties - Northern Ireland - being excluded.

Michael Collins grave in Glasnevin.

Some viewed the treaty as falling short of achieving full independence for Ireland; others felt it was a stepping-stone in accomplishing that overall goal. This profound divide resulted in the bloody Irish Civil War where Collins was gunned down in an ambush by anti-treaty forces. He was just 31 years of age.

Understandably, his funeral was the biggest in Irish history - almost 500,000 mourners flocked to the streets.

“Even British soldiers departing Ireland paid their respects,” Dara reveals. “They recognised his military genius.”

The romantics will delight in knowing that the grave of Collins’ girlfriend, Kitty Kiernan, is almost within arm’s reach.

Best of the Irish

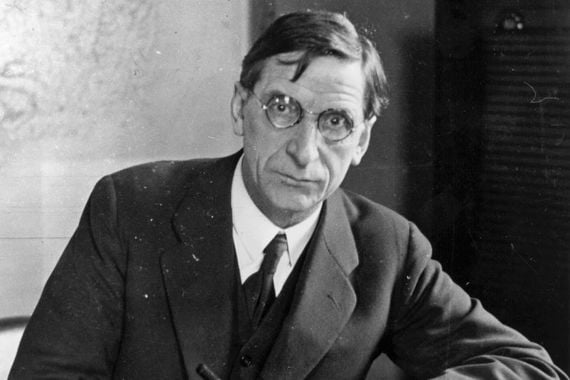

However, Collins’ rival during the Irish Civil War is also buried a stone’s throw away - Éamon de Valera. Saved from the firing squad during the 1916 Rising, he later served several terms as Head of Government and Head of State while also writing our constitution.

Éamon de Valera

“De Valera is a controversial and divisive figure in Irish history,” Dara says. “He was a remarkable man, highly intelligent - but also quite conservative, which is no longer as popular in Ireland. And his role in the Civil War - where he was anti-treaty – is considered controversial.”

Nearby are the graves of other prominent figures from Ireland’s fight for independence. Patrick Pearse’s stirring graveside oration at Fenian leader Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa’s funeral was a crucial precursor to the 1916 Easter Rising just months later.

Others buried in this plot include James Larkin, a founder of the Labour Party, and former Minister of Defense, Cathal Brugha, who, despite being shot by the British over 20 times during the 1916 Rising, survived by singing Irish national songs. He was later killed during the Civil War.

Trailblazer Countess Markievicz - the first woman elected to the British parliament in 1918, and the first cabinet minister in European history - is laid to rest nearby.

Countess Markievicz

“While she came from a very wealthy background, Countess Markievicz represented South Central Dublin, a very working-class part of town,” Dara reveals. “The people of Dublin loved her – and she is still well regarded even today.”

Peadar Kearney, who wrote Ireland’s national anthem, is also buried here - as is his nephew, writer and notorious drinker, Brendan Behan.

“Brendan famously said he was a drinker with writing problems!” Dara jokes. “People who like him get pints of Guinness from the Gravediggers nearby - my favourite pub in Ireland - and place it on his grave.”

Brendan wrote The Borstal Boy - a memoir documenting the three years he spent incarcerated in juvenile prison for being an IRA volunteer - and “The Auld Triangle”, a poem famously put to music by Luke Kelly, also buried here.

The graveyard shift

Other notable features in the cemetery are the high walls and watchtowers. They were built to deter body snatchers in the 18th and early 19th centuries - watchmen also had a pack of bloodhounds who roamed the grounds at night.

“It used to be illegal to touch a corpse under British law, which ran here at the time,” Dara reveals. “The problem was: doctors needed to dissect bodies so they could understand anatomy.

“That created a black market for dead bodies. Where could you get a dead body? The graveyard.”

With the help of a child, shovel, hammer and noose, they would surreptitiously remove the dead bodies before selling them to the medical schools. In the cemetery’s visitor’s centre, The City of the Dead exhibition highlights this grave-robbing phenomenon.

“Before COVID-19, we had already decided to put in place a major new design of the indoor visitor experience,” Luke O’Toole tells me.

“The new experience will be equally entertaining for those with a strong interest in Irish history, and those who want to hear interesting stories about the cemetery itself and the ‘ordinary’ people buried here.”

*Originally published in Ireland of the Welcomes Magazine in July 2022. Updated in May 2023.

Comments