St. Patrick's Cathedral, the Iveagh House and Gardens, St. Stephen's Green, housing for staff - everywhere you look in Ireland's capital you see Guinness's mark.

In school, I was fascinated with Guinness from a graphic point of view - especially their posters and advertisements,” my guide, Stephen Wall, reveals. “However, as soon as I began my architectural training, my interest became less about iconic marketing and more about the family behind the brand.”

As a student, Stephen remembers asking: Why does Dublin look like it does today?

“I soon discovered that so much of what exists in the city is thanks to the Guinness family.”

While folk memories remain about the brewery being good employers, Stephen concedes that few know the full expanse of their contributions to the city.

“The drink is, of course, celebrated the world over,” Stephen says, referencing the Guinness Storehouse, Ireland’s most popular tourist attraction, “but most people aren’t aware that the family donated so many landmarks to Dublin.

“I was determined to make sure that people knew about it.”

And so, using his architectural experience, combined with his passion for history, Stephen developed an exciting tour showcasing the Guinness dynasty’s impact on the city center.

Stephen takes me on a virtual journey into Georgian, Victorian, and Edwardian Dublin – deftly incorporating the best that technology has to offer including maps, videos, and imagery.

While the lion’s share of the tour focuses on the third, fourth, and fifth generations of the Guinness clan, Stephen begins with an overview of how the drink - now one of the world’s most successful alcohol brands - first started.

Humble Beginnings

Arthur Guinness was born in 1725, in County Kildare, and by all accounts, it was a humble upbringing. Stephen explains that at 27, Arthur was bequeathed £100 by his father’s employer, the Archbishop of Cashel.

Using this money - the equivalent to four years' wages at the time - along with the experience acquired from working in the brewery on the Archbishop’s estate - the budding entrepreneur opened his own small brewery in Leixlip.

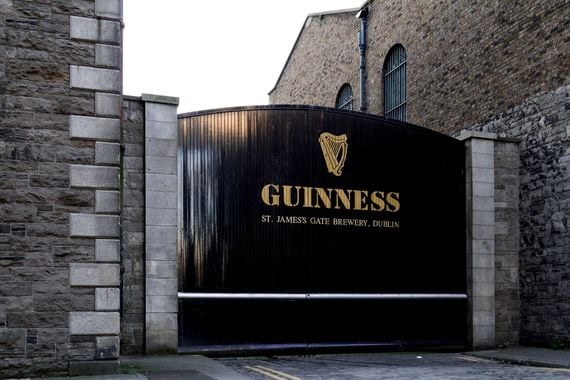

In 1759, drunk with ambition, Arthur left his business to his younger brother before venturing to Dublin, determined to make his fortune. Here, the 34-year-old signed a 9,000-year lease for a disused brewery at St James’ Gate just south of the River Liffey. The annual rent was £45.

The Guinness Storehouse, St James's Gate brewery.

Stephen says: “Initially, they brewed ale, but when Porter - a new black beer from Covent Garden - became popular, he abandoned ale completely, focusing on Guinness instead. The rest, as they say, is history!”

His son, another Arthur, clearly inherited his father’s business acumen and also proved to be a great master brewer. By 1838, Guinness had exceeded Beamish as the biggest brewery on the Emerald Isle.

Guinness's Gates.

However, when discussing the third generation, Stephen warns that things become a little complicated - and not only because another Arthur enters the story, albeit fleetingly.

“Arthur III was groomed to take over the business,” Stephen reports. “However, he had an affair with a male clerk who worked in the brewery - quite the scandal in the 1830s!”

This 18-year-old clerk was, in fact, playwright Dion Boucicault, who later achieved great theatrical success with The Colleen Bawn and The Shaughraun. As a result, a disgraced Arthur III was sidelined by his family and, according to Stephen, given a generous lump sum to purchase a house in Stillorgan, a leafy South Dublin suburb.

St Patrick's Cathedral

And so, younger brother Benjamin was given the responsibility of running the ever-growing empire. As Stephen points out his statue in front of St Patrick’s Cathedral, the National Cathedral of the Church of Ireland, I learn that Benjamin quickly dusted off his sibling’s scandal and soon became one of the wealthiest and most altruistic men in Europe.

St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.

While initially founded in 1191, and noted for having Gulliver’s Travels scribe Jonathan Swift as a former dean, St Patrick’s Cathedral had fallen into complete disrepair by the 19th century.

“Benjamin paid for the entire restoration,” Stephen says. “He planned to spend £20,000, but that figure eventually mushroomed to £150,000.”

This benevolence came with a caveat: in return for saving the building from imminent collapse, Benjamin insisted on acting as his own architect, which, according to Stephen, was an “eccentric and problematic” demand.

“Today, conservation practices are quite regulated. Now, we would restore the building as close as possible to its original condition. However, Benjamin was quite invasive - he retained some mediocre sections while destroying valuable historical fabric. In the end, he left us with a very beautiful personal interpretation of what a medieval cathedral could be.”

As a result of his philanthropy, Benjamin was elected Member of Parliament and received a much-coveted title.

“In the 19th century, to be anyone in society, you needed an aristocratic title,” Stephen mentions. “Otherwise, you were just seen as ‘new money’.

“Other than marrying an aristocrat, a title could be obtained through a government grant in recognition of philanthropy. This was possibly a motivation for Benjamin’s charitable works.”

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Sibling rivalry

But the Guinness’ generosity in this area was not limited to the cathedral. Benjamin inspired his two sons - Arthur IIII and Edward – to continue improving the city. Much to the benefit of Dublin, the brothers continuously tried to outdo each other with their philanthropy.

To say that this generation, the fourth, was colorful would be an understatement. Arthur IIII, or Lord Ardilaun, married Lady Olivia Hedges-White, daughter of the Earl of Bantry, thus ensuring his aristocratic bona fides. However, it was believed that they had an unconventional marriage with talk that, like his estranged uncle, he was gay.

Stephen describes Olivia as being a “snobbish wife” who firmly believed that the aristocracy should not get their hands dirty with jobs. And so, she convinced Lord Ardilaun to sell his share of the business to Edward.

It quickly emerged that Edward was more than capable of going it alone - demonstrated by shrewdly floating the company on the stock exchange while retaining a majority share, thus becoming one of the wealthiest people in the world.

Read more

The Iveagh Trust

Despite the many changes to the original business model, the competitive siblings gamely continued their father’s legacy. In the 19th century, following the Famine, Dublin had some of the worst slums in Europe, especially surrounding Benjamin’s prized St Patrick’s Cathedral.

Stephen reveals: “The Cathedral sat amidst a very rough area, with rampant poverty and prostitution. Not a great setting for the family’s greatest gift to Dublin!”

Edward, who would become Earl Iveagh in 1919, firstly donated a park immediately north of the cathedral.

“If you stand in the middle of the park, almost everything you see around you is connected to the Guinness family,” Stephen mentions, noting the surrounding red-bricked apartments. Called the Iveagh Trust, these apartments have housed thousands of low-income families for over a hundred years.

Notable original features include baths, a play center, and a Working Men’s Hostel that accommodates unmarried men including the late Patrick Kavanagh, one of Ireland’s greatest poets. A flat, inhabited by Nellie Molloy for 95 years, is now a museum and gives a sense of what it was once like to live there.

Today, the Iveagh Trust provides over 10 percent of the social housing in central Dublin.

According to Stephen: “Out of all the money the Guinness family spent on various projects across Dublin, the investment into the Iveagh Trust far exceeds any other venture.”

He continues: “What’s interesting about Lord Iveagh’s contribution to this area is that there was no hidden agenda. As a friend of the Prince of Wales, he had everything in addition to wealth, he boasted the all-important title.

“He genuinely discovered an interest in philanthropy.”

Dublin's Crown Jewel

Not to be outdone, his older brother and former business partner, Lord Ardilaun, was also active with his charity work. In addition to developing the Coombe’s Women’s Hospital and Marsh’s Library, his biggest success was returning St Stephen’s Green to the city - the next destination on our whistle-stop virtual tour.

Marsh’s Library, Dublin.

“Initially, it was a private park,” Stephen explains, “but by the 1880s, it had fallen into decline and so, Lord Ardilaun bought the land.” At the time, Central Park had just been completed in New York to great fanfare. The layout of St Stephen’s Green followed a similar design, which Lord Ardilaun funded. Today, this Green is one of the capital’s crown jewels - an oasis of calm in the center of a bustling European city.

In addition to a large pond, bandstand, and vibrant pops of color thanks to the many floral displays, the park features an embarrassment of riches including the Fusiliers' Arch and the Three Fates fountain. There are also tributes to the Great Famine, Constance Markievicz, W.B. Yeats, and James Joyce.

Fittingly, there is a statue of Lord Ardilaun on the western side facing the Royal College of Surgeons.

St. Stephen's Green, Dublin.

Iveagh House and Gardens

For the final section of the tour, we return a generation. To the south of St Stephen’s Green stands Iveagh House, once home to Benjamin who purchased two properties in 1862 before turning them into just one.

“As we saw with St Patrick’s Cathedral, Benjamin considered himself to be an amateur architect. Once again, with Iveagh House, Benjamin acted as his own architect, and created a beautiful neo-Georgian façade.”

Iveagh Gardens, Dublin.

For this façade, Benjamin used Portland stone, extravagant for a private house. Years earlier, during Georgian times (1714–1837), it was fashionable as it looked like marble, although on account of the cost, it was mainly used for public buildings.

Located towards the back of the property is the 17-acre Iveagh Gardens, often referred to by locals as Dublin’s “secret gardens”.

Here, in 1862, Benjamin co-founded the Dublin Exhibition Palace and Winter Garden Company - primarily intended as a permanent exhibition for Irish art. They were officially opened three years later by H.R.H. Albert Edward, Prince of Wales.

Stephen says: “At that time, there was a craze for exhibitions - cities like London, Paris, and Chicago were all hosting major international exhibitions.”

The gardens were landscaped specifically for the exhibition. Many of the original landscape features are still visible.

Highlights include the Rose Garden, an archery pit, fountains, and the maze, which is said to have been modeled on Hampton Court.

In 1870, two years following their father’s death, Lord Ardilaun and Lord Iveagh re-acquired the buildings and grounds from the Dublin Exhibition Palace Company. In 1883, Lord Iveagh retained the gardens for the family but sold the buildings to the Commissioners of Public Works. Twenty-five years later, these buildings became University College, Dublin; today, they are the National Concert Hall.

In 1939, Lord Iveagh’s son, Rupert, the fifth generation of the family, donated the Iveagh complex to the Irish State. While Iveagh House eventually became the Department of Foreign Affairs, Rupert insisted that Iveagh Gardens remain "unbuilt on" to provide a "lung" for the city. Thankfully, this stipulation is respected to this day.

Stephen concludes: “It simply cannot be overstated how much the Guinness family has done to benefit the city.”

I’ll certainly drink to that!

* Updated in 2024.

Comments