A human crush on 15 April 1989 at Hillsborough football stadium killed 96 people and injured 766. Ciaran Casey was one of the thousands of football supporters who watched the worst disaster in British sporting history unfold.

I got the train that morning. I had cut short a holiday home to Dublin and returned to Liverpool on the Friday evening. Liverpool had drawn Forest in the semi-final of the FA Cup and there was no way I was going to miss this one. The previous season, Liverpool had won the league and lost to Wimbledon in the FA Cup – this year we were on track to do the double. I was 26 years old, living and working in Liverpool and this was to be a day that I’d never forget.

I’ve never written about Hillsborough. In fact, I’ve never really spoken about it. I have read many reports, books and judgements and have seen many dramas and documentaries. I doubt there is any event that has been so forensically examined and analyzed.

So, when I think about it now, it’s hard sometimes to distinguish between details that I know to be facts because of what I have read and seen, and the details drawn from my own distinct memories. For example, the Taylor Report told me the train arrived in Sheffield just before 2pm and that most passengers were in the ground by 2.20pm. I don’t remember these times but accept them to be the case.

I had a season ticket for Liverpool’s home games but wasn’t a seasoned away supporter. Nevertheless, the train journey was relaxed and uneventful. I read a newspaper and chatted with other supporters about the game. Most of my fellow passengers were elderly or middle-aged, some with kids. There was an air of contained excitement as is the case before any big game. Otherwise, I have no standout memories of that train journey.

When we got to Sheffield, we were met by mounted and foot police who started to escort us from the station. This was bizarre as we were obviously a motley crew of harmless supporters and not the least bit threatening. All around us, supporters were getting off coaches and parking up cars to make their way freely to the ground. It was ridiculous that it was deemed necessary to provide an escort to those arriving by train. Despite this, everyone was in high spirits and good humored – loads of slagging (Scousers know how to slag).

At some point the police realized how senseless the whole escort thing was, so it just fizzled out and we were free to wander down to the stadium. It was an unseasonably warm sunny day and the atmosphere around the stadium was fantastic. I headed into the ground via the Leppings Lane end without incident and took my seat in the North Stand.

I had never been in Hillsborough before, so those early minutes were spent surveying the ground. As with any supporter, I was keen to see where the respective support bases were located. I was sitting in line with the goal, behind which the Liverpool fans were gathered to my right. Away to my left, behind the goal at the far end of the pitch, was the Forest end. I remember chatting to other supporters as the ground was filling up and kick-off was approaching.

At this point, it was clearly noticeable that the area immediately behind the Liverpool goal was congested while there was so much space at either side that I could see the concrete steps. I must admit that this observation was not made for any health and safety reasons. It was simply that the Forest supporters looked more of a collective that was ‘even’ and better organized and there was more of them. The Liverpool supporters, as a collective, looked fragmented and disjointed and I remember this bothering me. I wanted our supporters to look ‘well’ and as a single body, together in unison, because I felt that was important – idiotic thoughts I know, but I had them.

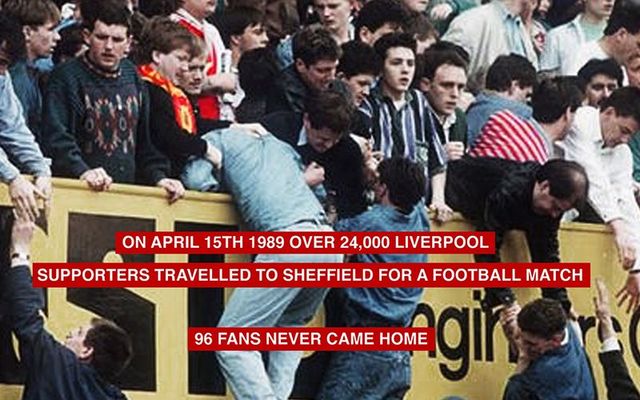

Crowds trying to pull people out of the crush Hillsborough.

I think it was just before kick-off that a supporter came in with his ticket intact saying that it was “crazy out there” but he took his seat and the game started. I don’t believe I ever got tuned into the game. The Liverpool supporters behind the goal were in my line of vision and there was something unsettling about what was happening. There was still plenty of space at the sides while the central area immediately behind the goal was obviously overcrowded. I had no understanding of the pen structure and was confused as to why they just didn’t spread out. I felt irritated that this was distracting me from the game.

I remember Liverpool hitting the crossbar and I remember trying to focus on the football but, by now, supporters were climbing over the fences onto the pitch. As more supporters spilled on to the pitch, a policeman and the Liverpool goalkeeper ran towards the referee and the game was abandoned. I remember starting to realize there was something wrong – wrong. This wasn’t a pitch invasion. These were desperate people trying to escape from horror. The look on their faces, the way they stumbled to find some space to sit down – totally exhausted. Some collapsed and lay prostrate on the pitch.

Meanwhile, supporters were being hauled up to the stand behind the terrace area as others tried to climb the pen fencing to access the empty spaces at the sides. Around the ground, some of the crowd were booing thinking this was an act of football hooliganism, which only heightened the desperation and panic in those that could see what was actually happening. Some police officers were preparing for confrontation while their colleagues close to the terrace did what they could to relieve the pressure.

The crowd on the pitch was increasing now and some supporters were trying to deliver first aid to their friends. I had been rooted to the spot watching this unfold – frozen, confused and in what I can only describe as a deep state of shock. I walked down to the pitch and I remember feeling like I was floating around what was happening, unseen and not really there.

Lying on the ground was a young lad, maybe 20 years of age. Around him were three of his friends desperately trying to give him CPR. They didn’t know what to do – nobody knew what to do. They called his name, pumped his chest, blew into his mouth and all the time were looking frantically around for someone to help. Yards away, another lad was lying on the ground while his pals worked on him and, close by, there was another and then another and then another. These harrowing images are ingrained in my memory. And as awful as they are, I am still to this day filled with respect and admiration for the courageous actions of these young lads. While all around them was in total chaos, they tried so hard to do the one thing they could do – save their friends from dying. In my mind, they were heroes.

Some of the faces of the 96 people who were killed in the Hillsborough disaster.

I don’t actually remember physically leaving the stadium though I do remember an atmospheric shift from being in the middle of these chaotic scenes to being in the middle of the more comforting silence of a stunned crowd outside the ground. I think I wandered around for a bit before asking a policeman for the directions to the train station.

These were the days before mobile phones, but the people of Sheffield opened their homes to let supporters use their home phones. I remember long queues of Liverpool supporters outside rows of houses waiting to call home. I think it was because I feared missing the train or maybe it was because I had no idea of the scale of the disaster but, for whatever reason, I didn’t join these queues, so it would be late that evening before family and friends were assured that I was okay.

The train journey back to Liverpool was long, tedious and very quiet. There were police on the train, but they wouldn’t answer any questions about how many had died. I remember thinking they knew but wouldn’t say. I knew some people had died and, chatting with other supporters, we made an estimate of somewhere between 15 and 20. There was some speculation as to how or why it happened, but we were very much in the dark and I think it was close to 10pm before we got back to Liverpool.

There were very emotional scenes at Lime Street station amid the bright lights of the TV crews. There was more chaos and confusion, with unbridled joy for some and quiet desperation for others, as they waited for the train that was due in later that night. I spent the rest of the evening listening because everyone knew more than I did but I’m pretty sure that nothing really sunk in. In the days that followed, the people of Liverpool struggled to come to terms with what happened, but they did so with dignity and respect. I was proud to be with them and felt privileged to have shared their grief.

What happened next was unthinkable – the newspaper lies, the police lie, the cover-up and the denial of justice was an extraordinary and sinister response to the worst disaster in British sporting history. With some notable exceptions, the entire establishment lined up to protect its authority by suppressing the truth. In response, Liverpool fought back and continues to fight – collectively, passionately and with a resilience that is as dogged as it is rare. Just like the young lads that fought to save their friends that day, Liverpool has more heroes that continue to fight for justice.

Sometimes when I look back at everything that happened that day and since, I can get overwhelmed with a combination of grief and anger. Anger can be a dangerous emotion, so I try to suppress it but it’s always there and maybe it always will be. The greatest wrong about Hillsborough was the established attitudes at that time toward football supporters – I believe this was the fundamental root cause of why Hillsborough happened. In perhaps the most class-structured society in Europe, football supporters were regarded as the lowest of the low. This perspective wasn’t just within the police; it was within the media, the body politic and the legal system.

The very institutions that have a duty of care to support and protect its citizens colluded to corrupt the truth and exacerbate the torment and distress of innocent people. I have to believe that those attitudes have changed. This is what I tell myself when the anger surfaces. This is how I explain it to my kids. It was a long, long time ago and something like this could never happen again.

Here's a BBC report, published in 2017, on what happened at Hillsborough:

* Originally published in Tatler Man.

Comments