“Rebellion runs in my family’s blood,” wrote Barney Rosset in his posthumous autobiography, the just published Rosset: My Life in Publishing and How I Fought Censorship (OR Books). “We have never shown a willingness to accept unthinkingly what authorities told us was right or wrong, in good taste or bad. The repression of imposed conformity has always been something we fought against, no matter what the odds.”

Rosset changed publishing in many ways. As the publisher of the Grove Press he was essential, along with Richard Seaver, in bringing the works of Samuel Beckett to a wide American audience. He was also instrumental in fighting the United States government and having the censorship ban on D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer lifted.

Rosset is the product of what used to be called a “mixed marriage.” His father was a non-religious Jew and his mother, an Irish-Catholic. Liberal politics, not religion, played the most important part when he was growing up as his mother was a big Al Smith supporter. As for religion, he said he “declared myself an atheist at an early age.”

There is absolute pride as he discusses his rebel Irish family: “On July 10, 1884,” he wrote, “in Carrick-on-Shannon, County Leitrim, Ireland, my great-grandfather, Michael Tansey, was sentenced to death for the murder of one William Mahon.” Mahon was a “British landlord’s man” and gamekeeper and his job was to keep poachers off the land. Rosset’s great-grandfather was convicted on trumped up charges. However, he was spared the death penalty, and Fenianism became part of the family’s DNA. His grandfather eventually made his way to Michigan where Rosset’s mother, Mary was born in 1891.

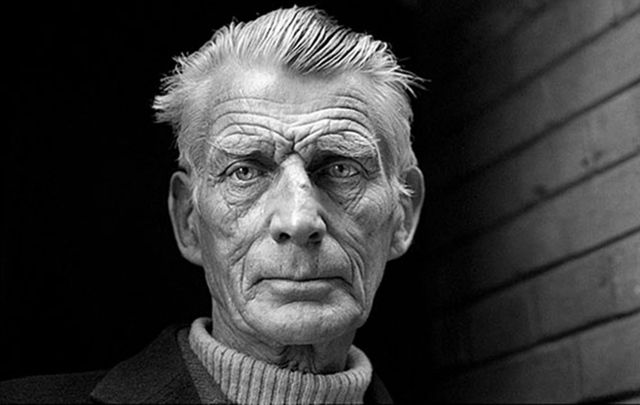

Samuel Beckett and Barney Rosset.

It is obvious that the Irish side of his family had the greatest impact on him as he was growing up: “My maternal grandparents, Roger Tansey and Maggie Flannery, retained their undying hatred for the English. No explanation of this was ever given to me. But I do vaguely remember hearing something about the Black and Tans from time to time. Although my grandparents spoke in Gaelic when they did not wish me to understand, I got the message quickly and never forgot it. British colonialism had brutalized Ireland and its native people. Indeed, Roger had left Ireland with a price on his head. Nevertheless, he was a very gentle man, tall, handsome, and the patriarch of the immediate neighborhood, which was largely made up of working-class people. Roger worked for the city, building and maintaining sewer lines.”

Hooking up with Beckett—with the help of Richard Seaver

Rosset may have been the American who published Beckett, but the late Richard Seaver is really the American who discovered Beckett. Seaver, who went on work with Rosset and Beckett at Grove and eventually started his own company, Arcade, first came across Beckett when he lived in Paris after World War II. Seaver wrote an essay on the then unknown Beckett and Rosset came across it.

Beckett and Richard Seaver.

On the centennial anniversary of Beckett’s birth in 1906, I interviewed both Seaver and Rosset about catching up with the reclusive Beckett. “Barney wrote me a letter,” Seaver told me, “saying, ‘I read your piece and I’m coming to Paris in the spring [of 1953] and can we meet?’ I said absolutely. We had lunch together and we talked a lot about Beckett. Barney wanted to meet Beckett and I said, ‘I’m not allowed, because Beckett was very secretive. I can’t give out his address. But here’s the name of his publisher and I will call the publisher and say you’re going to come by and see him.’”

“We met him at the Pont Royal Hotel in Paris,” Rosset told me. “He came in very jaunty, wearing a raincoat. Said he didn’t have much time. That would have been around seven and we stayed with him until four in the morning. It was very calm and very wonderful.” For a $1,000 advance, Beckett became a Grove author.

In 1959 Seaver joined Rosset at Grove. “I got a wonderful letter from Beckett saying, ‘I’m so glad you’re there, that’s where you should be, now we’re together again.’ So, for the next 10 or 12 years I was at Grove I edited his work. It was an enormous pleasure. He’s the most impeccable writer I have ever worked on.”

Walter Winchell thinks “Waiting for Godot” is a Communist play

The problem of who was going to translate Godot into English was a thorny one,” Rosset wrote in his autobiography. “Perhaps when Beckett wrote in French, no one looked over his shoulder, and he could achieve a more dispassionate purity. Perhaps he was also angry at the British for failing him as publishers. His novel Murphy and a short story collection, More Pricks Than Kicks, had achieved little notice in England. Perhaps Beckett felt he was too lyrical in English. He was always striving to strip away as many of his writer’s tools as possible before finally ceasing to write altogether—taking away tools as you would take away a shovel from a person who wants to dig.” Eventually, after much prodding, Beckett agreed to do his own translation.

Beckett was also worried about being censored, but Rosset told him not to worry about it. “And in 1956,” Rosset wrote, “Bert Lahr himself would perform the role of Estragon in the first American production of Waiting for Godot, which opened in a new theater, Coconut Grove, in Coral Gables. When it opened, Walter Winchell proclaimed it a Communist play. The joke of the week was: ‘Where is the hardest place in Miami to get a taxi?’ Answer: ‘Standing in front of the Coconut Grove after the first act of Waiting for Godot.’ Now the theater proudly celebrates the fact that the first American production of Godot was put on there.”

Beckett comes to New York and meets the Mets and Buster Keaton

Beckett only came to the United States once, in 1964. He came to make a film with silent film star Buster Keaton which, Beckett being Beckett, was called, naturally, Film.

Rosset tells about the Beckett-Keaton collaboration: “Sometime after Film was finished and being shown, Kevin Brownlow, a Keaton/Chaplin scholar, interviewed Beckett about working with Keaton. Beckett said, ‘Buster Keaton was inaccessible. He had a poker mind as well as a poker face. I doubt if he ever read the text—I don’t think he approved of it or liked it. But he agreed to do it and he was very competent. He was not our first choice …It was Schneider’s idea to use Keaton, who was available…He had great endurance, he was very tough, and, yes, reliable. And when you saw that face at the end—oh. At last.’”

Beckett and Buster Keaton on set of "Film".

During his time in New York Beckett was brought to a Mets baseball game by Seaver, who, by the way, was a second cousin of New York Mets Hall-of-Famer Tom Seaver. The 1964 Mets were awful and hopeless, so naturally Beckett took to them. These Mets played baseball as if they were in a Beckett play:

Ever tried.

Ever failed.

No matter.

Try again.

Fail again.

Fail better.

The Mets won the first game of the doubleheader and Beckett insisted in staying for the second, which surprised Seaver. The Mets, astonishingly, also won the second game. Seaver in his wonderful memoir, The Tender Hour of Twilight, recalls: “As we stood to depart, Beckett said with a sly grin, ‘Perhaps I should come to see the Mets more often. I seem to bring them good luck.’”

Except for the Mets, it seems that Beckett did not take to New York as Rosset tells the tale. “‘This is somehow not the right country for me,’ Sam told us at the bar. ‘The people are too strange.’ Then he said, ‘God bless,’ got on the plane, and was gone, never to return to the United States again.”

Rosset publishes Casement’s “Black Diaries”

Beckett was not the only controversial Irish author Rosset would publish. He also took a great interest in Sir Roger Casement’s notorious Black Diaries and decided to publish them.

“The British,” wrote Rosset, “said he was homosexual and the Irish said he wasn’t. But he was. He had written diaries while he was in the Congo, mostly about the treatment of people there, but he also wrote about his love affairs. The British brought out the diaries and the Irish said they were forgeries. What ultimately happened is the British came to the United States and got the Catholic Church to stop Irish Catholics from supporting Casement because they were raising all kinds of money for his defense. Maurice [Girodias] obtained the original diaries and published part of them and made him seem very sympathetic. I published the book here and received marvelous comments from Paul O’Dwyer, who said Casement was not homosexual. He understood immediately Casement’s importance. If you don’t get somebody mad, no one is ever going to hear about it. This was all due to Maurice, who wanted the world to know that Casement was a political renegade who was fighting for the rights of people in the Amazon and the Cong, who also happened to be gay.”

Friends to the last

Rosset sold Grove Press to heiress Ann Getty with the promise he would continue to run the company. It was not to be and he was soon fired. Beckett, a man who Richard Seaver called “the most faithful of writers,” took this as a personal affront. And like a lot of Irishmen, he had a long memory. Rosset tells the story:

“A later, thornier encounter at Le Petit Café involved Beckett and Peter Getty, son of the famously wealthy Ann Getty, who, with Lord George Weidenfeld, had bought Grove, in a sad story to come, from me in 1985. (After Getty and Weidenfeld promised to keep me as CEO, they would wind up ousting me without ceremony the following year.) Smart and young, Peter Getty, who often borrowed subway fare from Grove employees to get uptown to his Fifth Avenue apartment, had learned I was meeting Beckett in Paris soon after my ouster, and asked to be introduced. I agreed, and Getty flew over, checked into a suite at the Ritz, and taxied out to Beckett’s unlikely hangout, Le Petit Café, with a book he wanted autographed.

“This was the only time Sam was not friendly to someone I introduced him to. It was a short, tense meeting. After autographing the book, he glared at Peter and asked, ‘How could you do this to Barney, and what do you plan to do about it?’ Peter was very embarrassed, and mumbled something about consulting with his mother. Later, I heard that Beckett had told another suppliant from Grove, ‘You will get no more blood out of this stone,’ and he never allowed them to publish anything new of his again. To me and a group of others assembled in his honor at La Coupole he said, ‘There is only one thing an author can do for his publisher and that is write something for him.’ And he did exactly that. It was the little book called Stirrings Still. It was to be his last prose work, and he dedicated it to me.”

Their relationship was so close that Rosset named one of his sons “Beckett.”

Samuel Beckett died in Paris in 1989 at the age of 83. Barney Rosset died in New York in 2012 at the age of 89. Together their respective genius, once it came together, made publishing history.

Read more: 'All things come to an end': A last meeting with Samuel Beckett

* Dermot McEvoy is the author of The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising and Our Lady of Greenwich Village, both of which are now available in paperback, Kindle and Audio from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him at www.dermotmcevoy.com. Follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook at www.facebook.com/13thApostleMcEvoy.

Comments