Among the many people we lost in 2016, Tom Hayden was one whose death didn’t quite register among the political leaders, musicians and actors. A student radical in the 1960s, the Michigan-born Hayden was also a keen historian and scholar of the history of Irish America.

His 2003 book Irish on the "Inside: In Search of the Soul of Irish-America" called for Irish Americans to “reappraise” their history – as a poor, “foreign” people who came to the U.S. fleeing violence and starvation, hoping for a better life, and who were met with hostility when they got here. That understanding, Hayden argues, would allow Irish Americans to connect with others facing similar struggles today. Hayden contends that the Irish-American experience is one of forgetting: forgetting Ireland (or remembering it only as a “theme park”) and forgetting how hostile a place America was.

Let’s take a moment to remember the history of the links between Ireland and Connecticut.

This article appears courtesy of Connecticut Magazine.

The Earliest Irish

According to Neil Hogan of the Connecticut Irish American Historical Society, the first recorded Irish people in the state date back to the early 1600s, when several were brought to Connecticut as indentured servants.

In 1750, Matthew Lyon, a native of County Wicklow, was brought to Woodbury as the indentured servant of a wealthy merchant. After his indenture he moved to Vermont, where he joined the Green Mountain Boys under the command of Ethan Allen and fought in the Revolutionary War. When Irish revolutionaries back home, inspired by the American and French revolutions, organized the Society of United Irishmen in Dublin and Belfast to agitate and organize for an uprising to achieve independence from Britain, Lyon was one of the founders of the American Society of United Irishmen.

Canal Diggers

The first discernible wave of immigration came in the early 1800s. Throughout the United States, the Irish dug. They dug canals in New York (the Erie Canal in particular) and in New Orleans. Connecticut had its own version: the Farmington Canal and the smaller Windsor Locks Canal, which was largely dug by Irish laborers in the 1820s. The Farmington Canal, which opened in 1828, would for a brief period become a vital part of the growing Connecticut economy.

Writing for ConnecticutHistory.org, historian Richard DeLuca notes that “apples, butter, cider and wood flowed southward to New Haven, imports such as coffee, flour, hides, molasses, salt and sugar headed to towns upstream.” The canal would eventually prove to be too much of a loss-operator for its investors, and the growth of the emerging railroad economy would render it useless by the 1840s. In the fall of 2016, The Connecticut Irish American Historical Society and the Knights of Columbus gathered in Cheshire to unveil a new sign on what is now a walking trail, celebrating the contributions of Irish workers.

An Gorta Mór

While Irish immigration to the U.S. had previously been something of a trickle, the famine of the 1840s changed everything, both in this country and back in Ireland. The Irish-language name for the famine – An Gorta Mór, or “The Great Hunger” – reveals more truth than the more commonly known Potato Famine term used in English. The starvation and disease that cut the population of Ireland by roughly 25 percent – the population has still not entirely recovered today – was as much a product of Victorian economics and population engineering as the potato blight. John Mitchel, the political agitator who was deported to Australia, put it bluntly when he wrote “the Almighty, indeed, sent the potato blight, but the English created the famine.”

Mitchel’s quote is emblazoned on a video screen in Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum in Hamden, which is affiliated with Quinnipiac University. Because of the massive influx of immigrants – Connecticut’s Irish population exploded from 10 percent of the people in the state in 1850 to 25 percent in 1870 – the famine is in many ways the founding moment of Irish America.

Read more: Great Hunger museum at Quinnipiac an Irish American treasure

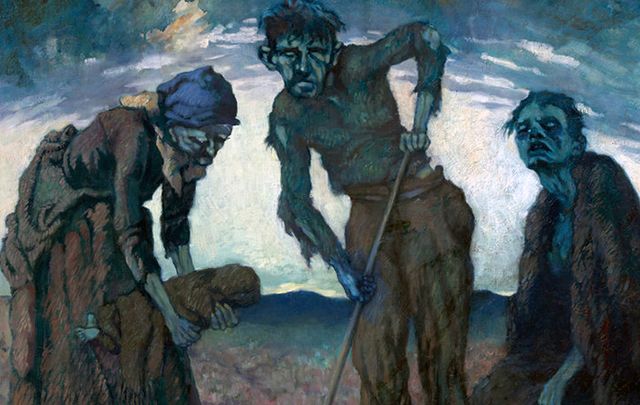

Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum asks difficult questions, rather than providing easy answers. How do we conceive of suffering? How do we remember devastation? The museum, says Executive Director Grace Brady, is “trying to tell the long story. You can’t survive on just telling the seven-year story [of the famine from 1845-1852].”

The museum itself, housed in a nondescript former public library building on Whitney Avenue, is designed as an expression of the famine story. First, the museum-goer enters a floor situated slightly below ground, into a low-ceiling, dimly lit space resembling a basement. The low light and cramped confines are gestures toward the conditions in which many Irish came to the country, cramped below deck in the disease-ridden vessels colloquially known as “coffin ships.” The profoundly affecting museum has also published a wealth of research and scholarship on the famine through its Famine Folios series.

Brady says the mission of the museum is two-fold. “The first part is the obvious: to teach people about the full story of the Great Hunger … not just about the potato crop, but that there was neglect by the government,” she says. “The second part of the mission is to showcase great Irish visual art, Irish and Irish American. Because nowhere anywhere is there a museum of this type that focuses on the story, and how to tell it visually,” she says.

One of the most arresting pieces in the museum’s collection is the sculpture "Surplus People" (2010-11) by Kieran Tuohy. It depicts a starving family, their forms ethereal and ghostlike, their faces haunting. Made from ancient oak pulled from Irish bogs that have preserved its form, "Surplus People" evokes the long history – embedded in landscape – that defines the Irish experience. In his poem "Bogland," Seamus Heaney identifies the Irish inclination to delve deeper into the self, in opposition to the American experience to drive West and settle the land:

They’ll never dig coal here,

Only the waterlogged trunks

Of great firs, soft as pulp.

Our pioneers keep striking

Inwards and downwards

The museum also features an exhibit on the travels of Elihu Burritt, a New Britain blacksmith who went to Ireland during the famine and delivered to American readers some of the most harrowing accounts of what he saw there. Burritt is widely credited as bringing the story of the famine to Americans.

Read more: Whatever happened to the compassion of the Irish?

The Civil War

Many of the Irish who fled starvation to come to Connecticut would find themselves caught up in the violence of the Civil War. While the famous “Fighting 69th,” the mostly Irish regiment from New York, is more well known, Connecticut had its own version. The Ninth Connecticut Infantry Regiment was formed in 1861, and led by Col. Thomas Cahill of New Haven. Attached to Gen. Benjamin Butler’s Army of the Gulf, they sailed from Boston Harbor for Mississippi, where the regiment saw action at Pass Christian. The Ninth Connecticut – with soldiers from counties Kerry, Cavan and Antrim – became the first Union regiment to capture Confederate colors.

A recruitment poster for Connecticut's ninth regiment Via Middlesex Historical Society

After securing their position at Pass Christian, they were sent to New Orleans, which had already fallen to Union forces, and eventually on to the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg. Just like in decades before, these Irish Nutmeggers dug. In this case, commerce was not their purpose. Rather, the Ninth Connecticut was tasked with digging a canal to divert the Mississippi River in an attempt to bypass Vicksburg and win control of the river.

In 1903, representatives from 28 states from both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line were invited to participate in the creation of a monuments park. Connecticut was snubbed, and so veterans and others interested in remembering the contributions of the Ninth Connecticut set about creating their own monument in New Haven, which still stands in Bayview Park in the City Point neighborhood. In 2008, a historical wrong was righted when Civil War enthusiasts gathered in the Vicksburg National Military Park to unveil a granite statue commemorating the canal dug by the Ninth.

Read more: Celebrating the Irish who fought in the Civil War

In an account from Lt. Col. John Healy, who served with the regiment, the Connecticut Irish soldiers were much more poorly equipped than their comrades in the 26th Massachusetts regiment. “The men were still wretchedly clad, and it was midwinter. Nearly half of them were without shoes and as many more without shirts; several had no coats or blankets. … The Twenty-sixth Massachusetts was equipped with warm blankets, ample tents, and two uniform suits of clothing per man; and to them the members of the Ninth furnished a contrast which would have been amusing if it were not humiliating,” Healy wrote.

After the war, James Mullen, a veteran of the Ninth Connecticut, became fire commissioner in the city of New Haven, and one of the original members of the Knights of Columbus. Mullen is buried in St. Lawrence Cemetery in West Haven. According to local historian Robert Larkin, Mullen is credited with originating the ceremonial regalia worn by Knights of Columbus members.

Connolly Comes

1916 hero James Connolly.

In 1902, Irish labor leader and revolutionary James Connolly came to Hartford on his speaking tour of the U.S. As Hartford historian and Connecticut labor activist Steve Thornton notes in his history of the International Workers of the World in Connecticut, the city had just elected the Irish American Ignatius Sullivan as its mayor. Having worked in a paper mill as a 10-year-old, Sullivan later became involved in organizing a number of strikes for the city’s workers.

While no record survives of what Connolly said at Hartford’s Germania Hall in September 1902, we know his speech was titled “Home Rule and Socialism,” and Connolly would later write in an Irish newspaper that “the cause of labor is the cause of Ireland, and the cause of Ireland is the cause of labor. The two cannot be dissevered.” Connolly returned to Connecticut in 1908, where, as noted by Neil Hogan of the Irish American Historical Society, he “ran afoul of the law when he set up his stand and tried to lecture on socialism on Main Street in Bridgeport.”

In 1916, Connolly led the Easter Rising in Dublin, regarded as the first blow in the fight for Irish independence, eventually culminating in the partition of the island in 1921. Wounded in the fighting, Connolly was executed by British firing squad while tied to a chair in Dublin’s Kilmainham Gaol.

This phase of the early 20th century was also a period of great social upheaval stateside. Among the many Irish-American radicals with ties to Connecticut, one state woman shines through. The Hartford-born Catherine Flanagan, the daughter of Irish immigrants, spent 30 days in jail after being arrested at a protest for women’s suffrage in Washington in 1917. In addition to her fight for the vote for women, she would campaign across the U.S. for the recognition of the Irish Republic by the American government. Of this period in Irish history and the links between Connecticut and Ireland, Hogan says, “I think it’s probably less known than it should be. There are some Irish who are very rabid about Irish history and there are some that have been here a long time, and they aren’t as enthusiastic about it or as interested in it. Overall, probably not as much as I would like to see people interested in it.” Hogan is the editor of Shanachie, the newsletter of the Connecticut Irish American Historical Society, as well as the author of the 2016 book "From a Land Beyond the Wave: Connecticut’s Irish Rebels, 1798-1916."

The Troubles

The formation of two states on the island of Ireland, one a sovereign Irish republic comprising 26 counties, and the other a statelet still ruled by Britain comprising the six northeastern counties of the island, would lead to yet more bloodshed and suffering on the island. Decades of discriminatory and brutal rule over the Catholic, Irish nationalist minority by the Protestant-Unionist majority in the North exploded into a civil rights movement in the late 1960s. That escalated into open warfare in the early 1970s that lasted for some 30 years of ethnic and political conflict – known as The Troubles – between Irish-Republican Catholic communities, British-Loyalist Protestant communities, the British Army and various paramilitaries. Connecticut, too, would play a role in both the war and the peace.

British soldiers in Northern Ireland during the Troubles.

Richard Lawlor, a Hartford attorney, former state representative and the vice-chairman of Irish Northern Aid (known as Noraid), was instrumental in generating American support for Irish Republicans throughout The Troubles. The organization raised money to send to the widows and families of imprisoned and killed Irish Republican Army fighters.

During The Troubles and today, many have contended that Noraid money was, instead, used to buy IRA weapons when it got to the island. Lawlor – who made his first trip to Northern Ireland during the 1981 hunger strikes, when 10 Republican prisoners died during a fast demanding political status in Long Kesh prison – today recalls “the complete military presence and militarization of the North. The border was very well armed. There was British troops everywhere, British forts everywhere.”

From Lawlor’s perspective, it took the advocacy and engagement of the Irish-American community by groups like Noraid to shift the American government toward advocating for negotiations between the British and Irish governments, Unionists and Irish Republicans in hopes of ending decades of violent impasse.

“The British government had a position that this was an internal British matter, that there’s no role for the U.S. And the successive U.S. administrations, and certainly the State Department, had acquiesced in that role for many, many years,” Lawlor says. “And there were a number of people, of us, who thought that – given what Irish people had contributed to America, and our philosophy of government and democracy – that we owed it to them to become involved to help them and to try to oppose British propaganda.”

After years of lobbying and pressuring American politicians, the U.S. State Department granted a U.S. visa in 1994 to Gerry Adams, the leader of Sinn Fein, widely understood as the political wing of the IRA. In the 1990s, during what we now know as the early stages of the peace process (which would result in the historic Good Friday Agreement of 1998), Connecticut politicians were instrumental in tying together the various strands of Irish-American political thought into a cohesive political lobby.

Bruce Morrison.

One of the most important figures in this story is Bruce Morrison, a three-time U.S. Representative from Connecticut’s Third District. According to the 2016 book "Peacerunner" by New Haven lawyer Penn Rhodeen, Morrison was convinced to dive headfirst into Northern Irish politics by two events. In 1987, Morrison visited the Northern Irish city of Derry, and in a particularly tense moment, was searched and interrogated at gunpoint by the notoriously sectarian Royal Ulster Constabulary, the police force of the Northern Irish state. The moment left a lasting impression on Morrison, and pushed him toward action.

Another key moment came when Lawlor asked Morrison to join the Ad Hoc Committee for Irish Affairs, the congressional grouping which favored Irish unification and had ties to Noraid. The committee was more avowedly political than the more mainstream Friends of Ireland, whose “major concerns seemed to revolve around St Patrick’s Day,” Rhodeen writes. Morrison’s staff advised him not to meet with Lawlor, because of his IRA sympathies, but Morrison found Lawlor persuasive and joined the committee. Morrison “was happier tackling serious questions instead of wondering which green tie to wear on St. Patrick’s Day,” Rhodeen writes.

Throughout the 1990s, Morrison acted as a key intermediary between the Irish Republican movement and the Clinton White House, in a process that would lead to an IRA ceasefire and eventually bring Sinn Fein into government with Unionists.

In 1997, in a lasting gesture to the relationship between Connecticut and Irish Republicanism, Lawlor and other members of the Irish-American community unveiled a memorial to Bobby Sands, the first of the 10 hunger-strikers to die. The memorial – a stone Celtic cross inscribed with the Irish phrase “Tiocfaidh ár lá” (“our day will come”) at the corner of Maple Avenue and Freeman Street in Hartford’s South End – remains one of the few memorials to Bobby Sands in the world outside of Ireland, the others being in Havana, Paris and Tehran.

Asked why Hartford played such an outsized role in The Troubles and the Peace Process, Lawlor says the Irish-American community in Hartford was unique. “We had a particularly active unit [of Noraid] here, and everybody kind of stayed together. The Irish, they say that once you form an organization, the first item on the agenda is the split, but we didn’t have that. We didn’t have that, everybody stuck together,” Lawlor says.

Today, almost 19 years after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, and centuries after the first Irish immigrants came to Connecticut, there is still traffic between the two places. In the fall of 2016, Irish airline Aer Lingus commenced a direct flight from Bradley Airport to Dublin, and Irish-American community centers across the state continue to keep alive a sense of Irish identity.

Read more: Aer Lingus flights between Connecticut and Dublin take off

* Michael Lee-Murphy is a Belfast-born, New England-raised, Quebec-Schooled reporter and writer. He is a staff writer at Connecticut Magazine, writes the blog A Furious Return to Basics, and tweets at @mickleemurph.

Comments