Almost all who left Ireland during the 19th century never saw their homeland again. Letters home are the only way we can experience what they went through.

Kerby Miller featured many such letters in his groundbreaking "Emigrants and Exiles."

Here are a few of them:

Cathy Greene. Brooklyn, New York. To her mother in Ballylarkin, County Kilkenny. August 1st, 1884

My dear Mamma,

What on earth is the matter with ye all, that none of you would think of writing to me? The fact is I am heart-sick, fretting. I cannot sleep the night and if I chance to sleep I wake with the most frightful dreams.

To think it’s now going and gone into the third month since ye wrote me. I feel as if I’m dead to the world. I’ve left the place I was employed. They failed in business. I was out of place all summer and the devil knows how long. This is a world of troubles.

I would battle with the world and would never feel dissatisfied if I would hear often from ye. And know candidly things are going on but what to think of how ye are forgetting me. I know if I don’t hear from ye prior to the arrival of this letter at Ballylarkin I will be almost dead…

I sometimes think you would come here and that health would fail and like almost all the Irish, drop off one by one. There is no place like home if one could at all live there but if not don’t hesitate about coming here.

I trust ye are well and that my frightful dreams won’t be realized.

Cathy

Old Chapel, Skibbereen, Cork, during the Great Hunger.

Mary McLean Walsh. Describing the emigration of her family from County Leitrim to Canada in the summer of 1832. Written or dictated to her daughter, Sarah Kirwan in Ottawa.

On the tenth of May, 1832, my parents with their eight children sailed from Ireland to America; and, although the other passengers fared very well, and notwithstanding I was a perfectly healthy Irish girl of sixteen, during the whole voyage of one month, I was ill….We were much relieved to be landed in Quebec but imagine our feelings at finding ourselves in a plague-stricken city; where men, women and children, smitten by cholera, dropped in the streets to die in agony, where business was paralyzed, and naught prevailed but sorrow mingled with dread and gloom.

…people passed us, each holding, between their teeth, a piece of a stick, or cane about the length of a hand, and as thick as the stem of a clay tobacco pipe, on the end of which was stuck a piece of smoking tar. We learned this was used as a preventative.

Read more

My father, seeing my weakness, engaged rooms nearby… the following morning I was advised to dress, and walk slowly on the wharf, which I did; and was passing a heap of coal there when, suddenly, blinded and speechless, but conscious, I fell against it. The captain of our ship who was standing near talking to another gentleman, ran forward and raising my head told his friend to bring from the ship, as quickly as possible, a tumblerful of brandy with a teaspoon of red pepper stirred through it…

I was now in a veritable house of torture, where the most appalling shrieks, groans, prayers and curses filled the air continually.

As if in answer to this, day and night, from the sheds outside came the tap, tap, tap of the workmens’ hammers, as they drove the nails into the rough coffins, which could not be put together hastily enough for the many whose shrieks subsided into moans which gradually died away into silence not to be broken.

Whose poor bodies were then carried to the dead-house in the hospital yard, confined, piled on the dead cart and hurried off to what was called the cholera burying ground; where, so great was the mortality at the time, corpses were buried five and six deep with layers of lime between, in one grave.

All the medical men’s efforts to save were futile, until I fell into their hands. And as I slowly, but surely, recovered such interest was centered on my case that four doctors, at a time would stand bending over me, noting anxiously, each symptom of returning health. In spite of their watchfulness, however, I twice managed to disobey orders.

On a long table in the ward in crocks each with a little dipper beside it stood the drinks allowed us – brandy and water, lemon juice and water without sugar and very thin gruel without salt, but none of these satisfied me, for my bed was near the window, through which could be seen a well and this set me dreaming often with tear-filled eyes of mother’s well far away, over whose low brim some big old country roses drooped, seeming to impart their fragrance to the limpid deliciousness beneath. And I craved incessantly for one drink of clear cold water.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

So, one day when my mother who regardless of all danger to herself, had braved the horrors of the hospital, to help nurse her four children – three sick of cholera, and one of small-pox, which also was raging in 1832 – had gone away for a much needed rest, I coaxed the nurse to gratify my longing…

Finally my pleadings touched her so that she brought me a small cup of water, which I drank greedily. It had no bad effect whatever and the doctors in spite of all their watchfulness detected nothing unusual.

A little later, enlisting the sympathies of the nurse, who had helped in my former venture in what I persuaded her was a good cause she bound me to secrecy and smuggled in a cupful of warm broth, which I swallowed and in a few hours was once more on the verge of the grave.

As mine was the case on which the doctors’ hopes hung, this relapse caused them much distress: the head physician declaring, angrily that some one had tampered with me; but ill as I was all efforts to make me divulge were useless: and the nurse a big, jolly Irishwoman, declared when we were alone that I was a ‘little brick’ and that she was proud of her countrywomen.

My disobedience very nearly cost me my life, but a good constitution triumphed and six weeks from the time of entering the hospital I was sent to the recovery sheds adjoining where sad to say, some, who were cured of cholera contracted small-pox and returned to the hospital and died.

While in the recovery sheds we were allowed daily, the juice of six lemons and a handful of peppermints. My father brought me a fresh supply of both each morning and at the end of a week was told he might take me away.

As I walked for the last time in the hospital yard, I saw, burning there, cholera-tainted rich velvet and silk gowns, costly bonnets and shawls, children’s clothing the rags of the poor, gorgeous uniforms, boots with spurs attached and all else which formed a pile almost as high as an ordinary house.

Read more

As I watched the flames creep upward, I realized that, before me was indeed a shocking proof of the ravages of the plague. And breathing a prayer for the souls of the dead, who had once worn those garments, I took my father’s arm and set out, all sadness giving way to the joyful anticipation of a family reunion, not knowing that my own sisters’ and brothers’ clothes were in that burning pile I had left behind, until I met my Mother, dressed in deep mourning, her pretty face sad and care-worn when she told me I was the only one of her four sick children who had survived.

Famine Memorial in County Sligo.

Robert Smith in Philadelphia to his parents in Moycraig, County Antrim. August 14, 1844.

..I now hold a respectable situation in this city as a custom house officer….I have the honor of being appointed through my own merit. We have in the Custom House 200 officers and there are only three Irishmen in that office and I am one of those.

I owe to that the stand that I have taken the political field. I am a Democrat out and out and take the platform for the cause against monarchy and aristocracy. I am for free Republican government.

…our city has been nothing but the scene of bloodshed. The origin of this awful scene was respecting a party of native American citizens forming themselves into a body to deprive all foreigners of their rights and privileges guaranteed to them by the constitution.

And they pitched their spite upon the Irish Roman Catholics and at one of their meetings the Irish rose against them and there was a great number shot on both sides. There were a great many Roman Catholic churches and nunneries burned in the city and as many as fifty killed in one riot. There were 20 cannons discharged in one night by the military.

There is an issue with the module you added.

The following is a letter from Ireland. Michael and Mary Rush from Ardnaglass, County Sligo write to their father, Thomas Barrett, in Carillon, Ontario. September 6th, 1846.

Dear Father and Mother,

Pen cannot dictate the poverty of this country at present, the potato crop is quite done away all over Ireland and we are told prevailing all over Europe. There is nothing expected here, only an immediate famine…

Now, my dear parents, pity our hard case, and do not leave us on the number of the starving poor, and if it be your wish to keep us until we earn any labor you wish to put us to we will feel happy in doing so.

If you knew what danger we and our fellow countrymen are suffering, if you were ever so much distressed, you would take us out of this poverty Isle. We can only say the curse of God fell down on Ireland in taking away the potatoes, they being the only support of the people. Not like countries that have a supply of wheat and other grain.

So, dear father and mother, if you don’t endeavor to take us out of it, it will be the first news you will hear by some friend of me and my little family to be lost by hunger, and there are thousands dread they will share the same fate…

So I conclude with my blessings to you both and remain your affectionate son and daughter.

Michael and Mary Rush

P.S. For God’s sake take us out of poverty and don’t let us die with the hunger.

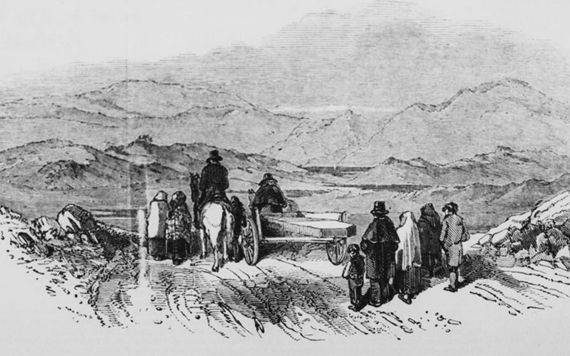

A family fleeing home during the Great Hunger.

Thomas Reilly, Albany, New York, to John M. Kelly, Dublin. April 24th, 1848

Dear John,

I am going to renew our correspondence and ungenerous should I be if I failed, in doing so, to express the deep regret I feel at being separated from you. Perhaps, this is the only way in which I shall ever again converse with you, perhaps it is, alas. This moment how my heart sinks, and tears start into my eyes.

I am a slave in the land of liberty…. Nothing save death could lull the storm which is raging in my mind. When I took out your prayer book in the chapel today, I thought my heart would break, not because it is weak, but, friendless, deserted and lonely….

There are Irish Volunteers preparing in America to invade Ireland in case of an emergency. My name is enrolled on the list and we are drilling ourselves for the occasion. Perhaps, I will return to Ireland with green flag flying above me. I care not if it becomes my shroud. I have no regard for life while I am in exile.

We expect to muster 50,000 men in a short time, God send them soon. If that force were shown on the southern coast of Ireland, we would quickly march to the city of Dublin and set it ablaze.

25th day. I ceased writing on Sunday evening to learn the light exercise and the several military squares. The mod by which we will be sent to Ireland is to go to France first. This is a project which I think will be hardly carried out, tho there are plenty of volunteers proposing themselves.

Since I began this letter there were one hundred houses burned in this city.

Read more

I will now give way to some of my adventures. I left Dublin on the 19th Feb. I arrived in Liverpool on the 20th, took out my passage tickets the same day, did not sail for America until 1st March….

Well I set sail and our ship, the ‘Patrick Henry,’ was resolved to bring us to the South Sea Islands instead of to New York. We had the two first days very fair and rounded the Irish coast like a sea gull, the wind followed in our wake for three days on the Atlantic.

The forth day the Monsters of the deep showed their heads, the Captain said we would have a storm, and truly Boreas spent his rage on us that night. We were tumbled out of our berths, the hold was two feet full of water, a leak was gaining an inch a minute on us, our topsails were carried away, the most of male passengers were all night reliving each other at the pump and in the morning I left my hammock at seven o’clock to look at the terrible sea. …

How will I describe a gale on the Atlantic as follows…. At five o’clock p.m. all hands were tuned up close reef sail, not a stitch of canvass to be seen spread, six o’clock wind right ahead, the vessel lying to a rolling from side to side like a heavy log as she was, the passengers quaking with fear.

Ten o’clock, the scene below no light, the hatches nailed down, some praying, some crying some cursing and singing, the wife jawing the husband for bringing her into such danger, everything topsy turvy, - bar- rels, boxes, cans, berths, children rolling about with the swaying vessel, now and again might be heard the groan of a dying creature, and continually the deep moaning of the tempest.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

The scene above, bare poles, thunder and lightning, the ship almost capsized, lying on her beam, sheets of water drenching her decks, the sea swelling far above her masts, engulfing her around, and huge billows striking her bows and sides with the force and noise of a thousand sledge hammers upon so many anvils.

The ship receding with every wave, sometimes standing perpendicularly on her stern and shaking like a palsied man and then plunging decks and masts under water and raising to renew the same process. She would screech with every stroke of the waves, every bolt in her quaked, every timber writhed, the smallest nail had a cry of its own.

One o’clock in the morning, not a soul on the deck, standing upright, oh mercy one of our masts has gone over the side, bulwarks stoved in, 30 tons of water washing the decks from stem to stern. The Captain is panic struck. Tom Reilly is waiting on the quarter deck to get into the life boat.

The captain speaks, carpenters cut away the broken spars, look out for the next spar, here it comes, The Mizen top is carried away. The ship lurched on her side and lay in a state of distress until day light.

We had 15 storms one greater than another.

26th day. Dear John,

I forgot to tell you, my ship was foundered on a sandbank within two days sail of New York. She ploughed thro six feet of sand. The vessels going to New York generally cross the banks of Newfoundland which are northerly but I kept southerly and therefore passed thro the stream of the Gulf of Florida.

Curious sights are to be seen in the gulf, the phosphoric lights, sparkling like diamonds, the varied colors of the firmament, occasionally a shark, moving majestically thro the water and other different things too numerous to mention.

We had severe weather in the gulf, yet we were fortunate. An unfortunate vessel from New Orleans bound for Liverpool was struck by lightning. She was laden with cotton, it took fire. Oh that was an awful sight. Our ship was far in the distance but the Margaret of Newry saved the crew of the burning craft, a great deal of property consumed.

She burned down to her coppers and resembled a pillar of fire all night. Was not that a poor sight on the wide sea. It shocks me even now. Several other affairs happened but how can I relate them here, with a heart bowed down by weight of care. After a voyage of five weeks we landed in New York….

I would advise no one I have regard for to emigrate unless the persons interested to come have friends before them, who will receive them and snatch them from all the evils of Society. You would hardly believe were I to tell you, all the trials, cheats plots and chicanery of every kind which I had to overcome.

If a man has seven senses, it would take 500 senses largely developed to counteract the sharpers of Liverpool and New York. It would be worth the teaching for a man to come here. The women, (I mean the Irish) are great slaves in this country. Oh the profligacy of some are awful.

I was in the worst company human nature could produce since I left Dublin – robbers, swindlers, pirates, smugglers and swearers and the worst of the lot was an Irishman, but his conduct does not impurely reflect on his countrymen. If it did, what was to become of me?

I found a generous black the other day and I roaming in a wood. He brought me into his boolie (bualtin, Gaelic for little house,) and although I shared his hospitality the smell of him gave me a headache. I had a rifle with me. He fired several shots and did not once miss his aim. I left him alone in his glory and came home.

I wrote to my mother. If she bids me to go home I will go. If not I will wander along the pleasant valleys of the Mississippi, pay a visit to New Orleans, the battlefield of General Jackson, and if I live, return to the land of my birth next spring.

Write and answer quickly – tell me the whole status of affairs and one request I ask of you is to show this letter to my mother….

I have no intention to stop in Albany. The Irish volunteers expect to go to Canada to raise the standard of revolution. If they do I will go along with them…

I now send my devoted aspirations to Mrs. Kelly. My running away without seeing her, whom I prized more than tongue could tell, has caused me many a gloomy hour since we partied. She forgives me. I was not aware my departure would be so sudden.

At all events I did not wish to see her on the night of the 19th as my nerves were braced and tho’ the tumult within was intense had I gone to her house my iron heart would melt. It was enough for me to see you on the beach, all lonely…

I am going to the mountains, my native element, this afternoon. Send me the United Irishman, or the Nation.

So farewell, the dearest companion of my last years. I sigh to close our long divided conversation. I shall think of you in my hours of melancholy.

Thomas O’Reilly

Peter Connolly in Fort Smith, Arkansas to his father Thomas Connolly in Carrickmacross, County Monaghan. May 11th, 1848

My Dear Parents and Brothers,

…I got such a shock by the news contained in your letters that it weighs heavy on my mind ‘till this minute.

It would not be so much so if I had been able to send help to my suffering friends and to a moral certainty it would have been on the road before now only for a loss I sustained about the middle of April last, which was $100 worth of wood which I had on the bank of the Arkansas river to sell to the steam boats but unfortunately the river overflowed its banks in April and took from me the labor of six months at least.

My most sanguine hopes of making a little money and assisting my distressed parents and brothers being thus cruelly frustrated I got on a steam boat as soon as I could with my family and left the place where I experienced so much mortification.

I saved as much of the wood as paid for my passage up the river to Fort Smith and I am now living in an Irishman’s house. He has no family and is well off as to living. He makes us welcome to make it our home ‘till we make a home for ourselves which I hope in God will be in the latter end of next fall.

I can get 3 shillings a day British currency for my labor, without diet and everything I need to live on is so cheap that it costs but very little to support a man and his family here.

Indian corn 1 shilling per bushel; bacon two and a half pence per pound; flour one penny per pound; Irish potatoes one shilling per bushel; a good cow and her calf for 20 shillings to eight shillings; I might say pigs for nothing. Recollect that this is the price in this town – a town very little less than Carrickmacross in size…

I address myself to my friends. I would say to them come here one and all and don’t hesitate one moment about coming, but how mortifying is the idea that my friends must be debarred from the privileges of such a country as this merely for the want of funds.

50 shillings a head being the fare to New Orleans. Is it, or can it be possible, that the times are so bad that this sum cannot be realized by any person that wanted to come to America? But I believe that there are a great many people in Ireland so trifling as not to come here even if they could.

* Originally published in 2015, updated in Oct 2024.

Comments