Once sung by descendants of the 7th Cavalry, Irish air "Garryowen" will no longer cause pain for Native Americans.

“Garryowen,” an Irish drinking song with a marching cadence, is to Native Americans what “Deutschland Uber Alles” is to Jews, a hated reminder of the evil past.

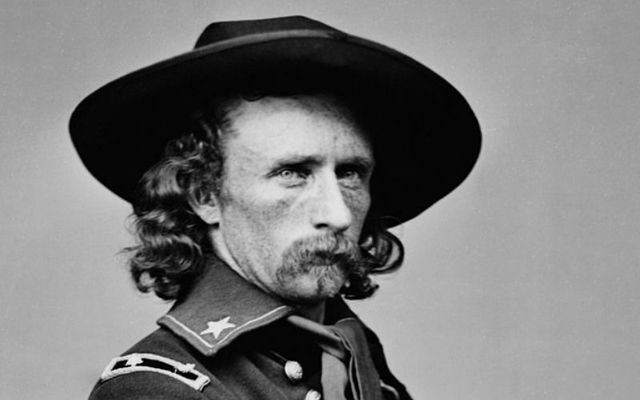

“Garryowen” was the marching song of the 7th Cavalry and the infamous Lt Colonel George Custer when they massacred native American villages in the all-out campaign in the 1870s to rid the plains and the west of “redskins.” The tune was played quite deliberately right before the attacks.

Now, it is played no more by descendants of the 7th Cavalry forces.

It is worth explaining why.

It was played at the battle of the Washita in Western Oklahoma in 1868 just a year after Custer was allowed to resume his command after being court-martialled for visiting his wife at a remote army post.

Custer was put in charge of the attacks on the native Americans by General Phil Sheridan, the son of two Irish immigrants from County Cavan and a Civil War hero. He was merciless in pursuit of his quarry.

Custer loved his regimental song “Garryowen,” a Limerick drinking tune, sung by his Irish soldiers, which featured that brisk marching cadence.

On his way to Little Bighorn in 1876 – the last time he was ever seen alive – his band played “Garryowen” as they passed out of sight of their fort for the last time. At the Little Bighorn over two hundred men, including 34 Irishmen, were ambushed. All were killed by Cheyenne and Lakota warriors led by the famed native American fighter Crazy Horse.

At Washita, Custer and 700 men of the 7th Cavalry crept up on an unsuspecting native American village and played “Garryowen” to signal the start of the battle before plunging into the village and destroying everything and everybody around them. Up to 100 men, women, and children were massacred.

The Cheyenne long resented that some of the bodies killed, including babies, found their way to Native American museums and were never properly buried.

On the 100th anniversary in 1968, a Cheyenne museum returned the body of a Cheyenne child to the tribe who gathered at Washita to bury the baby in sacred tribal ground.

7th Cavalry relatives, known as the “Grandsons of the Seventh Cavalry,“ descendants of 7th cavalry members, and relatives of the Cheyenne at Washita joined together at the ceremony. The 7th Cavalry captain Eric Gault was presented with the blanket that had wrapped the baby’s coffin as a gesture of goodwill, an incredible kindness.

Deeply moved, he, in turn, handed over his badge containing the name “Garryowen” and promised the original would never be played again by the 7th Cavalry relatives.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Lawrence Hart, a Cheyenne peace chief, remembered the captain approached him crying.

“He took a pin from his uniform and said, 'Lawrence this is the Garryowen pin worn by the original members of the 7th Cavalry. It is the signal to attack. I have taken it off my uniform and I want you to have it on behalf of the Cheyenne people. We are sorry that 'Garryowen' was played that day 100 years ago and never again will it be played against your people.’”

For the Cheyenne, the gesture was similar to Jews never having to listen to Wagner, a notorious anti-Semite.

It can be remembered as a noble gesture. The dreaded “Garryowen” will never ring again across the American plains or the American West for the native Americans. And the old native American ghosts can rest in peace.

* Originally published in 2017. Updated in August 2024.

Comments