In "The Greatest Beer Run Ever: A True Story of Friendship Stronger Than War," Chick Donohue and New York Daily News columnist Joanna Molloy tell the astonishing true story of Donohue’s legendary 1967 beer run to visit his Irish buddies fighting in Vietnam. Cahir O'Doherty hears Donohue’s outrageous tale of his epic one-man quest to bring support, laughter and beer to his friends.

You've heard of going the extra mile for your friends? What if it’s an extra 8,644 miles to bring beer all the way to Vietnam? Right through the middle of the infamous Tet Offensive? That’s doing your buddies the kind of favor that qualifies for sainthood.

In "The Greatest Beer Run Ever: A True Story of Friendship Stronger Than War," well known New Yorker John “Chick” Donohue and New York Daily News columnist and reporter Joanna Molloy tell the astonishing true story of one young man who was determined to honor his friends at a time when most of the world wanted to forget them.

Donohue, 75, grew up in Inwood at the top of Manhattan back when it was one of the most Irish neighborhoods in the city. Back then on the playing courts beyond Park Terrace West, you could hear accents that ranged from Cork and Kerry to Dublin and Donegal.

It was tight knit, in other words. They lived in each other’s shadow in the Irish manner, and Donohue adored it.

Without having to leave the city, he had learned all the regional accents of Ireland. Later when he reached 17 he followed his brother into the Marine Corps the way sun follows rain.

By 1967 at the age of 26, Chick was a veteran working as a merchant seaman. One night, the story goes, he was in a New York City bar discussing the progress of the Vietnam War.

Inwood had one of New York's highest numbers per capita of soldiers serving in Vietnam, and on this particular night the gathering did a head count and realized that between them all they had been to 30 funerals in Inwood alone.

"Inwood had one of the highest numbers of soldiers per capita serving in Vietnam from New York."

Worse, the boys who were still signing up, most of whom were aged between just 18 and 19, were having to push past throngs of protestors outside the draft board, and the atmosphere was about as heavy as could be.

Reflecting not so much on the political divisions that were tearing the country apart as on the faraway boys who were fighting a war without their country’s full support, someone suggested that one of the men present should sneak into Vietnam, search for their New York buddies and bring them beer, a bear hug, some laughs and a word or two of support from home.

It seemed like a completely mad idea because it was. Chick Donohue raised his hand and said, “I’ll go.”

Within two days, he was on board a cargo ship bound for Vietnam. He carried a map, a list of the lads' names, and messages from home. He also carried beer, as much of it as he could carry.

“One particular day I had been walking through Central Park and there was a huge anti-war demonstration and I just fled from it,” Donohue tells the Irish Voice.

“I wanted to get the hell away from these people. I just thought they were traitors. It was the fall of 1967 and I was thinking of the guys I knew who were serving over there, and the guys who had died over there. They were all people I knew from Inwood.”

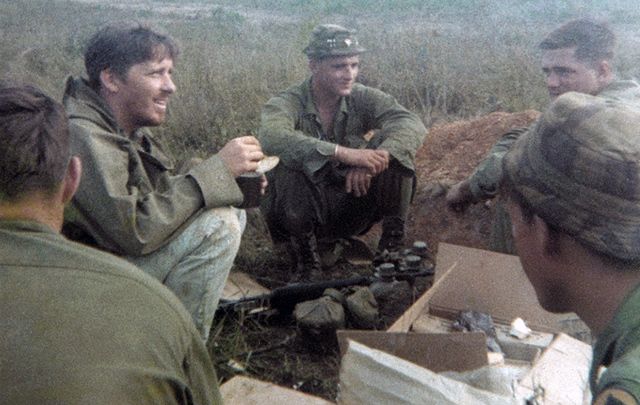

Chick Donohue, right, in Vietnam, delivering beer to a friend from back home.

The boys he was thinking of were of “the age when you didn’t even think about ages, anywhere from 18 to 25,” he says. Donohue had just turned 26 and was himself too old to go.

“I wasn’t thinking about the political aspect. I felt so sad for them. How could I explain to them what was happening in our city when they were over in Vietnam getting killed defending our way of life? “

The Summer of Love and Sergeant Pepper were not on Chick’s mind.

“I was 26. I wasn’t a kid, and I wasn’t out sowing my oats still. I had to pay bills and I was in a different frame of mind from an 18-year-old.”

What was on his mind were all the boys from his neighborhood, all of whom were in Vietnam. “I don’t know how many funerals of young people you have been to? I had seen enough. I had to do something.”

Little Johnny Knopf from Dyckman Street had just turned 18 when he was killed in Vietnam, Donohue says.

“That really affected me. I tried to stay in the funeral parlor with him that evening. I tried to hide in the men’s room when they were closing up late at night. I know I was acting crazy. I didn’t want Johnny to be laying up there in that box all by himself.”

Johnny was the first of many. He had been so full of life, the life of the party. He “bounced like a puppy” Donohue recalls, still haunted by the memory five decades later.

“And there he was in his uniform and polished medals, laying in his box. Eighteen years old. I just felt that it was wrong to leave that kid alone there that night.”

From the way he talks you begin to get the picture. Donohue would have brought beer to those boys if they’d been stationed on the moon.

Later a worker found Donohue hiding in the bathroom. He understood, but he insisted Donohue leave.

When the idea was suggested that he take a trip over to send them greetings from home he was ready.

“They gave me some notes to carry, then I caught a bus from 42nd Street to New Jersey, to the old steam ship the Great Victory. I was on my way.”

What did they say when they saw him coming, Pabst Blue Ribbons in hand, these young lads he had grown up with?

“They didn’t know I had beer,” he laughs. “They could see I was a civilian because I had relatively long hair. Then they saw my loud madras print shirt. I looked like a mad tourist.

“They likely assumed I had a legitimate reason to be there until they spoke to me and discovered I didn’t. It wasn’t planned that way. I didn’t give a thought to it.”

Some of these lads, privately, had assumed they might never see America again, Donohue realized. But his appearance was so mad, so completely unexpected, it must have tempted them to imagine they might just make it home.

What did they talk about? “I told them what was going on back in the States. Never once did we talk about the danger they were in,” he recalled.

But the danger they and Donohue were in at all time was considerable. In fact, he was present when the Vietcong staged the Tet Offensive, one of the biggest military campaigns of the war.

What he thought had been New Year’s fireworks turned out to be a massive military offensive to take back the U.S. Embassy, the airfield and Saigon.

The details of Donohue’s journey, as recounted in this gripping book, are terrifying when you consider that he volunteered to enter this lethal conflict.

Book cover for “The Greatest Beer Run Ever: A True Story of Friendship Stronger Than War.”

But those who witnessed it first-hand perhaps best understand the real importance of this story. When co-writer Joanna Molloy interviewed one of the veterans who luckily made it home, his wife insisted that he wouldn’t talk to her.

“He doesn’t talk about Vietnam,” she said. “Not to the kids, not to his brothers and sisters, not even to me and I’m married to him. I don’t think he’ll talk to you.”

But then Molloy said she was calling to ask about what it felt like to see Chick Donohue arriving all the way from home with beers for him and his buddies. The former veteran laughed in the background and picked up the phone. For the first time in five decades he told them all about it.

"The Greatest Beer Run Ever: A True Story of Friendship Stronger Than War" is available on Amazon.com for $24.99.

Comments