The Irish Land War was an organized campaign of civil unrest in Ireland that lasted from the 1870s until the 1890s.

It was called a 'war,' and there were violent incidents and deaths during the campaign, but the Land War, led by the Irish National Land League, was essentially a non-violent movement of tenant farmers with the aim of resisting the landlords' efforts, backed by the British government, to evict tenant farmers who were struggling the pay the ever-increasing rents.

Still struggling to recover in the aftermath of the Great Hunger in the 1840s, these poor tenant farmers were often exploited by landlords, especially by “absentee landlords,” those landlords who lived outside of Ireland, who raised rents without regard to what the farmer could pay or what the land could bear.

The eviction of Thomas Considine at Moyasta, County Clare. IMAGE: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND.

Evictions were widespread. The Land League organized resistance movements throughout the country hoping to reduce rents and to put an end to the threat of eviction facing many of Ireland's tenant farmers. When nothing more could be done to stop an eviction, however, tenants often took to barricading their cottages and taking up an odd assortment of arms in an effort to prevent police from removing them.

Police shield themselves against hot water thrown by tenants while carrying out an eviction. IMAGE: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND

The images here are from the National Library of Ireland and were taken around 1888. They show some of the efforts by tenants to protect their homes, while police took up battering rams to remove their protections.

Constables surround the home of boatbuilder Francis Tully on land owned by the Marquis of Clanricarde at Woodford, County Galway. IMAGE: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND

With thorny bushes placed in windows and doors to prevent armed police and British soldiers from entering, boiling water and cow dung was fired at them by tenants to warn them away when they came with an eviction order.

A building in Mitchelstown bears an anti-eviction banner and has its windows barricaded with brush to repel attacks. IMAGE: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND

Although the number of evictions never reached the same levels as they did during the famine, some 100,000 families were left in rent arrears due to the economic situation in the country by 1879. Thanks to the work of the National Irish Land League and The Ladies Land League, a movement numbering approximately 200,000 people helped prevent of the disastrous total of evictions from the famine years was avoided in the late 1870a.

A laborer's family outside their temporary turf hut after being evicted from their home. IMAGE: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND

This was achieved by drawing attention to specific cases of eviction and placing national pressure on the landlords trying to remove tenants from their homes. One of the most high-profile of these led to the introduction of the concept of a “boycott” to the English-speaking part of the world. In 1881, landlord Captain Charles Boycott was ostracized by the local community in south Co. Mayo in what became one of the most effective methods of campaigning by tenants.

The scene before an eviction in County Clare. A disassembled battering ram is brought in on a horse cart. IMAGE: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND

Not every family was as lucky. Speaking about an eviction in Tully in 1888, William Henry Hurlbert stated, “Two constables were burned by the red-hot pikes, the gun of another was broken to pieces by a huge stone, and a fourth was slightly wounded by a fork.”

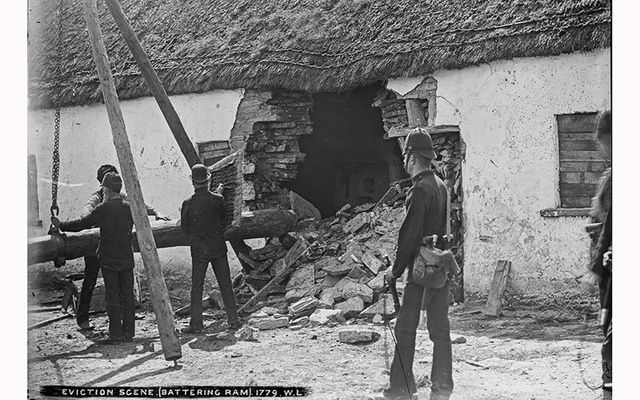

A battering ram is used to breach a farmer's home. IMAGE: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND

“On the morning of the eviction we were up at the break of day and laid our plans, each to defend a certain point and none to waiver, whatever might come,” said Frank O'Halloran of his family’s eviction in 1887.

IMAGE: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND

“We boiled plenty of water and meal, and, when all was ready, we kept a lookout for the bailiffs and the rest of them. At this time I was only home a few months from America, and during my absence, I may add, I did not learn to love Irish landlordism or English rule.

Mathias McGrath's home in Moyasta, County Clare after destruction by a battering ram. IMAGE: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND

“I got a big pole: there was a policeman at the top of the ladder; I put it to his chest, pushed him into an upright position. The policeman behind him pressed him on, while the crowd yelled, wild with delight. I shoved harder and he fell to the ground, amidst deafening cheers and shouts. Others pressed on, to meet the same fate.”

The scene at the eviction of Thomas Birmingham in Moyasta, County Clare. IMAGE: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF IRELAND

H/T: Mashable

* Originally published in 2017, updated in April 2023.

Comments